Cypress Stave Cisterns in South Louisiana: Meaningful Markers on the Cultural Landscape

By Marcia Gaudet

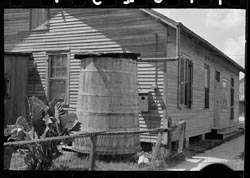

In the nineteenth century, large wooden cisterns were the standard source of potable water in homes in southern Louisiana. These cisterns were indeed huge barrels, made of cypress staves1 and banded with galvanized rings. Rainwater from the roof was diverted through gutters into the cisterns. When the cisterns filled with rainwater, the cypress staves would swell, creating tight seals. The water was then piped from the cisterns into the homes. Because of the high water table in the area, well water is not only unsuitable for drinking and cooking, but it was usually too brackish or muddy for bathing, washing clothes, or cleaning as well. Water from the Mississippi River was equally unsuitable.

Every home had its own cistern. Cisterns varied in size, and large plantation houses often had more than one. In Back of the Big House, John Michael Vlach notes the immense size of the typical cypress cisterns—10 feet by 8 feet barrels—near plantation houses throughout southern Louisiana (1993, 36). He also notes that "the Fannie Richie mansion in Pointe Coupee Parish once had two such cisterns set on tall brick bases at the rear of the building" (Vlach 1993, 36). This appears to have been typical of large plantations, such as San Francisco in Garyville, Whitney Plantation in Wallace, and Evergreen Plantation in Edgard.

French-born artist Adrien Persac captured the landscape of southern Louisiana in many paintings of plantation environments, including cisterns, in the mid-nineteenth century. In Marie Adrien Persac: Louisiana Artist, H. Parrott Bacot and his co-authors present commentary on the paintings of Persac and note the presence in the paintings of two or three large barrel cisterns near many of the plantation "big houses." Among those noted are Faye Plantation in St. Mary Parish (Bacot et al. 2000, 42), Ile Copal in Lafayette Parish (50), Lady of the Lake in St. Martin Parish (52), Orange Grove in St. Mary Parish (60), and Union in St. James Parish (80).

Cypress stave cisterns were also the source of water for houses in the French Quarter and for the mansions in the Garden District of New Orleans in the nineteenth century. In Life on the Mississippi, Mark Twain says of the mansions in the Garden District, "No houses could well be in better harmony with their surroundings, or more pleasing to the eye, or more home-like and comfortable-looking" ([1883] 1984, 303). He goes on to say:

One even becomes reconciled to the cistern presently; this is a mighty cask, painted green, and sometimes a couple of stories high, which is propped against the house-corner on stilts. There is a mansion-and-brewery suggestion about the combination which seems very incongruous at first. But the people cannot have wells, and so they take rainwater. Neither can they conveniently have cellars, or graves, the town being built upon "made" ground; so they do without both, and few of the living complain, and none of the others. (Twain [1883] 1984, 303-304)

Craig E. Colten, in An Unnatural Metropolis: Wresting New Orleans from Nature, points out that at the turn of the twentieth century in New Orleans, "Given the groundwater conditions, most residents relied on cypress cisterns that collected rainwater from their roofs. There was some concern about the safety of consuming this water too, however. . . . Nonetheless, in 1872 about 78 percent of the households had cisterns" (2005, 61). According to Colten, "Cistern water had enjoyed a decent, if not excellent, reputation until the municipal water company began discrediting it in the late nineteenth century. Although cisterns collected foreign material washed from the roofs, devices were available to divert the initial runoff during a rain storm and accept only water that flowed across a rinsed surface" (2005, 65). Colten also notes that cisterns were normally emptied and cleaned annually.

In 1909, there were twenty-three cistern builders listed in the New Orleans city directory, including Rigmer & Wahlig, whose business card boasts that they are "The Largest Cistern Factory in the South." Most residences still collected rainwater in cisterns for drinking and cooking. In that year, the New Orleans Water Board's purification plant began providing pure drinking water into the city's homes.2 While New Orleans had purified water available in homes, it would be much later before rural areas, small towns, and plantations had water purification plants. Many homes even in New Orleans continued to rely on cistern water.

Marion S. Oneal describes her own family's reliance on cistern water in the late nineteenth century and the early twentieth century in "Growing Up in New Orleans":

Along three sides the Mississippi held the city of New Orleans in the soft curve of its protecting arm. But we did not drink the river water or use it for household purposes. . . . For baths, cooking, washing dishes, and all other household uses, we depended on the big two-story wooden cistern sitting behind the house and taking up most of our back yard. Rain fell on our slate roof and was carried in gutters to the great barrels. When the cistern was full, a waste pipe brought the water down to the little drain in the yard which carried it down the alleyway to the big gutter along the street. (1964, 85)

Cisterns could be problematic, however, in times of drought, and Oneal describes her family's experience with the cistern in their yard:

One summer we noticed the hoops slipping on our big tank, and soon we could see daylight through the top staves. Then one day there was a crashing noise, and the great cistern's hoops slid to the ground. The staves opened across the backyard like a giant daisy, its center a cushion of black mud that oozed all over the yard, bringing with it worms, slime, dead birds, and fuzzy little dead things. The neighbors kindly divided their scant supply of water with us until the stinking mud was cleaned up and the cistern rebuilt. . . . (1964, 85-86)

By the early twentieth century, municipal water systems provided water for homes in cities and larger towns, but cisterns remained the source of household water in rural areas until the 1950s or even the 1960s in some areas. Even then, many people kept their cisterns for drinking water. In 1963, Fred Kniffen notes that cypress cisterns were still part of the small-farm assemblage in rural Louisiana, remaining long after other structures were gone. Kniffen says:

Cypress cisterns for accumulating rain water, outdoor bake ovens, several small frame outbuildings, paling fences enclosing houses and the inevitable china-ball trees, and post-and-rail (pieux) fences setting off fields and lanes, all are part of the type small-farm assemblage. The shotgun house of French Louisiana also stands in curving rows along bayou bank or road. The cypress cistern is present, but the outbuildings and other appurtenances of an agricultural economy are largely missing. (1963, 269)

Kniffen also notes, "Traditional practices continue to flourish even after their original function is forgotten" (1963, 297).

Eric Roussel, a native and resident of Edgard, shared memories of cisterns in the 1940s and early 1950s. His recollections sound very much like those of Marion Oneal. He said that everybody had them, and when the weather was dry, they would dry up. He also noted that they were a mess to clean, with "mud and stuff at the bottom." His grandfather, J. B. Camille Graugnard, was an owner of Caire & Graugnard and Columbia Plantation in Edgard. The Graugnards had a very large cistern, pictured in family photos from around the late 1920s (Conversation, March 2017).

In the 1950s and earlier, most of the cisterns in Vacherie and Edgard were built by Jean Waguespack. A few months before her death in 2009 at age 80, the late Marie Therese "Shoon" Hymel of Wallace said that Jean Waguespack had built the cistern at her family's house in the 1950s or earlier. Later, it had been taken apart, moved, and rebuilt by Edwin "Menew" Gravois of South Vacherie. Mr. Gravois, who died in 2014 at the age of 79, was a carpenter who also repaired and rebuilt cisterns.3

In the decades following the 1950s, it had become increasingly difficult to find a woodworker who could repair or build a cypress stave cistern. Eventually, most of the cisterns fell into disrepair and were abandoned, but some were maintained—both on plantations along the Mississippi River and at more modest private residencies. A ride along rural roads will also reveal the continuing presence of some examples of cisterns along the rivers and bayous.

Retired District Judge G. Walton ("Ton") Caire of Edgard lives in the home that was his parents (Mr. and Mrs. Sidney Caire), next door to Caire's Store. He had the cistern behind his house repaired in 1999 or 2000 by Ray Weimer from Thibodaux. The cistern was taken down and rebuilt, with a few boards replaced. The cistern is still operating and still collects rain water. Judge Caire said he uses the cistern water mainly for watering plants and flowers, but he still likes having the cistern in his yard.

Cistern builder Ray Weimer of Thibodaux has been a featured presenter on "Cypress Shingles and Water Cisterns" in the Louisiana Crafts Tent at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival for many years. His son Danny Weimer now builds cisterns and presents with him at Jazz Fest.

Alfred Schexnayder, owner of the former Schexnayder's Bakery (now La Bon Boucon) in South Vacherie, had a cistern moved to the side of the traditional Creole cottage that housed the bakery. He said it was a cistern from a house "on the river," dismantled and rebuilt by Alfred Roger ("T-Shawn"). Schexnayder stressed that no nails are used in the construction of cypress stave cisterns. The galvanized rings are the key. There is a groove at the bottom of each cypress stave that goes into the floor of the cistern. He said, "When you remove the rings, the boards come apart." (Conversation, March 2009)

There is also a young cistern maker in Breaux Bridge, Brandon Begnaud, who taught himself to build a cypress cistern when he wanted one for his own home. He now has a Facebook page and an Internet website advertising his business, Southern Cisterns. An article by Ruth Laney in Country Roads Magazine (2012) explains how Begnaud became a cistern maker.

Cisterns are re-appearing on the cultural landscape, both as renovated old cisterns (often moved to new locations) and some newly constructed. They are often part of heritage sites and tourist attractions, particularly plantations. Cisterns are also attractions at living history and rural life museums, such as Acadian Village and Vermilionville in Lafayette and the LSU Rural Life Museum in Baton Rouge. There was a cistern at the home of the late Patricia Rickels, folklorist and professor at UL Lafayette. The Rickels had purchased the cistern in the late 1960s and had it moved from its location at a rural home near Lafayette and rebuilt on their property located on the Vermilion River. Elaine Bernard, who inherited the home and property from Dr. Rickels after her death in 2009, wanted to donate the cistern to Vermilionville in 2010 but it was too deteriorated to move and rebuild.

Cisterns have been depicted in works of art as well, including the many paintings by Adrian Persac in the nineteenth century. Other examples include "Cypress Cistern, Shadows-on-the Teche, New Iberia," an 1878 watercolor by artist H. Hattendorf. A contemporary painting of a cistern by Thibodaux artist Dan Junot is titled "Cajun Waterworks." A photograph of a cistern with the shadow of a fiddle player is used on the cover of the book Becoming Cajun, Becoming American by Maria Hebert-Leiter (2009).

As fewer and fewer people in Louisiana actually remember functioning cypress stave cisterns as a source of potable water, there appears to be an increasing interest in these cisterns as significant, meaning-laden markers on the cultural landscape. This interest appears in part to stem from the architectural placement pattern of house and cistern on the landscape. The cypress stave cistern is perceived as an aesthetically pleasing artifact of vernacular design. Cisterns are also meaningful symbols of cultural self-sufficiency and identity, and there is a fascination with the utility of the cistern as part of the narrative of the independent, self-sustaining household of Louisiana Cajuns and Creoles. The large cistern in the middle of a traffic round, surrounded by flowers and welcoming motorists to Youngsville, seems to function not only as a welcome sign to this Louisiana town, but as a symbol of the culture.

As Henry Glassie points out, "Buildings, like pots and poems, realize culture" (1999, 227). Louisiana culture is realized as well in the cypress stave cisterns, historically examples of what Glassie calls "technologies based on local skills and materials" (1999, 239). Like the vernacular architecture of Ballymenone, they are "emblems of cultural presence" in southern Louisiana (1999, 239).

In the words of Kent Ryden, "Place is created when experience charges landscape with meaning" (1993, 218). Cypress stave cisterns were a vital component of the Louisiana landscape, and for a long time they were a necessity of everyday life. They continue to be a part of cultural identity and memory. Their perceived beauty and utility contributed to the idea of the cistern as a meaningful symbol of place in South Louisiana. People see beauty and purpose in the old cisterns.

Notes

1. Staves are the narrow vertical strips of wood placed edge to edge to form the sides of the cisterns or barrels.

2. Barbara Bacot says that the 1905 yellow fever outbreak in New Orleans was the impetus for the city's campaign against cisterns and wells. The connection of yellow fever with mosquitoes was discovered by Dr. Walter Reed during the Spanish-American War.

3. Special thanks to my niece Mary Lynne Hymel Chabaud for obtaining this information for me.

Sources

Bacot, Barbara SoRelle. 1994. "Louisiana Cisterns and Wells." Preservation In Print, October: 6-7.

Bacot, H. Parrott, et al. 2000. Marie Adrien Persac: Louisiana Artist. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

Colten, Craig E. 2005. An Unnatural Metropolis: Wresting New Orleans from Nature. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

Glassie, Henry. 1999. Material Culture. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Hebert-Leiter, Maria. 2009. Becoming Cajun, Becoming American. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

Kniffen, Fred. 1963. "The Physiognomy of Rural Louisiana." Louisiana History 4, vol. 4: 291-299.

Laney, Ruth. 2012. "The Rain Barrel Maker: Southern Cisterns." Country Roads Magazine May 27. http:// countryroadsmagazine.com/art-and-culture/people-places/the-rain-barrel-maker-southern-cisterns/.

Oneal, Marion S. 1964. "Growing Up in New Orleans: Memories of the 1890's." Louisiana History 5, vol. 1: 75-86.

Ryden, Kent C. 1993. Mapping the Invisible Landscape: Folklore, Writing, and the Sense of Place. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press.

Twain, Mark. 1984 (orig. 1883). Life on the Mississippi. New York: Penguin Books.

Vlach, John Michael. 1993. Back of the Big House: The Architecture of Plantation Slavery. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.