The Treasured Traditions of Louisiana Music

By Ben Sandmel

It is no exaggeration to say that Louisiana is one of America's richest sources of traditional ethnic music. Louisiana has produced many important musical styles and definitive and talented performers. Every part of the state has made important contributions that have influenced popular music far beyond its borders.

New Orleans' unique blend of cultures nurtured some of the most significant developments in the emergence of jazz, with fresh ideas still evolving today. Rhythm & Blues also made great strides in New Orleans, and likewise continues to evolve. In addition New Orleans is an important center for rap music and hip-hop music, which are ultra-modern styles with distinct folk roots.

Many nationally-renowned blues artists learned their craft in the blues clubs of Baton Rouge. To the west, the cities of Lafayette, Lake Charles, Eunice, and Opelousas—and the rural prairies in between them—are home to Cajun music and zydeco. South Louisiana also spawned a blend of these styles with rock and rhythm & blues that is known as "swamp pop".

Shreveport is vitally important in the histories of country music, rockabilly, and the blues. So are such other North Louisiana cities as Monroe, Alexandria, and Ferriday, and the adjacent rural reaches of the Delta parishes, the piney woods, and the Kisatchie Forest. Gospel music is also a significant tradition in these areas as well as throughout the entire state, in both black and white communities.

Immigrants from a wide variety of nations have brought along their traditional music and added them to this rich cultural blend. These sounds include the Isleño ballads known as décimas of St. Bernard Parish, which are sung in a 17th-century Spanish dialect from the Canary Islands; Italian music, and its fascinating interaction with jazz and rhythm & blues; salsa, merengue, and other styles from Central America and the Caribbean; the music of such Asian nations as Vietnam and Laos; and many more.

This essay introduces Louisiana's musical traditions, with emphasis on the dominant traditions. It appears in conjunction with 35 brief biographies of musicians that comprise Louisiana's Legendary Musicians: A Select List. Louisiana can generally be divided into three folk-culture regions: New Orleans, South Louisiana, and North Louisiana. Because of cultural similarities, the Florida Parishes are considered part of North Louisiana for purposes of discussion. (See Louisiana's Three Major Folk Regions Map.) The cultural borders between these three regions are fluid and flexible. In general, North Louisiana is predominately Protestant and primarily populated by English-speaking British Americans (also referred to as British Americans), and African Americans. South Louisiana is principally Catholic and populated by Cajuns and Black Creoles. (The term Creole has many varying uses in Louisiana, as discussed later in this essay.) Many residents of South Louisiana still speak French today, although not exclusively, or are descended from French-speaking ancestors. New Orleans, Louisiana's largest city, was historically settled by French and Spanish Catholics and a large population of slaves brought straight from Africa or, indirectly, from Caribbean nations such as Haiti. British Americans followed, as did immigrants from Italy, Ireland, and Germany. In recent decades, New Orleans has become home to large immigrant communities from Latin America and Southeast Asia.

In the same vein as these designated cultural regions, various terms will be defined and discussed here. These terms serve as important points of reference for educators, researchers, and folklorists. In addition, the division of music into stylistic categories is essential for music-related businesses such as radio stations and retail stores that sell music recordings. The definitions of these terms are generally agreed on by educators, folklorists, and music-industry professionals. Nevertheless, these definitions are not universally accepted. Opinions often vary as to the necessary criteria for various musical genres, and the appropriate inclusion of musicians or compositions within a certain category. Heated disagreement often arises. In addition, musical jargon, like all living language, changes over time. Furthermore, some terms emerge retroactively; "swamp pop," for instance, was coined in the 1970s to describe music that originated in the 1950s. There is also considerable debate over the differences between traditional music and commercial music, and how to distinguish the two. Finally, musical categories are often unimportant—if not downright annoying to people who actually earn their living as musicians. Therefore, the terms presented are guideposts, but additional sources may present different interpretations.

Most Louisiana music is performed in small venues where the audience responds by dancing. In recent years, Louisiana music has come to command large audiences around the world, especially the musical styles of New Orleans and South Louisiana. For the most part, when Louisiana musicians perform overseas, they play on the stages of concert halls or festivals. Some foreign audiences may dance to Louisiana music, but the atmosphere, social context, and the dance steps are usually far different from a performance for locals back home.

juke joints and at bluegrass festivals and Mardi Gras runs

Cajun music and zydeco, for instance, are often performed at community nightclubs, dance halls, traditional gatherings such as boucheries, trail rides, Mardi Gras runs (or courirs), and at festivals. These festivals range from small events within the immediate community to large gatherings, such as the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, that draw huge crowds from the world. Blues, rhythm & blues, and Latin genres are also performed at clubs, dance halls, community events, and festivals. The backwoods blues clubs are sometimes referred to as juke joints. New Orleans jazz is played in similar venues, and also performed on the streets of the city, in elaborate parades at second-line gatherings, and funeral processions. The term second-line is thought to refer to the group of people who follow the parading bands at such events. Like many musical terms, it has other usages: a second-line also refers to a gathering that includes a street parade and brass bands, etc. In addition, second-line is also used as an adjective, in describing second-line rhythms or second-line beats - the syncopated, Afro-Caribbean rhythmic patterns that that are often heard in much of New Orleans jazz and R&B.

Country music, too, is performed at clubs and festivals. During the 1940s - 1960s, some of the more rough-and-tumble country nightspots were known as honky-tonks, a term which was also applied to a country-music style that was popular at the time. This term is not frequently used today, however. Some country musicians, particularly those, who blend secular and religious material, will not play at any event where alcohol is served. Not surprisingly, many gospel musicians feel the same way, reinforcing a long-held belief that secular venues, such as bars, serve the devil. However, there are some gospel musicians who believe that they can effectively spread their message to non-believers by playing at nightclubs. In recent years, gospel brunches have become popular at secular venues in New Orleans.

New Orleans

The music that the public most commonly associates with New Orleans is jazz. Beyond its popularity, jazz is also the subject of much debate. One thorny issue is New Orleans' status as this great music's literal and exclusive birthplace. While these claims are overstated, the city's crucial contributions to jazz are undisputed. Nineteenth-century New Orleans provided a uniquely fertile social climate for jazz to first appear. Jazz can be defined as an American form of music that combines African, European, and Caribbean elements. Improvisation and syncopation were two of the most important traits of this new form of music, and they remain important today. (Syncopation can be defined as the use of varying rhythmic emphasis within a song, in "push and pull" fashion.)

The influence of African culture in jazz is particularly strong. In most southern states, slaves were not allowed to assemble in public, and overt expressions of their African heritage were strictly forbidden. But in New Orleans, where the ruling class lived in fear of slave rebellion, cultural expression was regarded as a safety valve for tensions that might otherwise trigger political revolt. On Sunday afternoons large, officially sanctioned gatherings of slaves in Congo Square, occurred on the present site of New Orleans' Municipal Auditorium. African and African-rooted dancing, singing, and drumming provided the passionate entertainment at these events, as people who led harsh lives enjoyed collective release. This weekly spectacle attracted many observers from outside the slave community, and was documented by such noted authors as George Washington Cable. The Mardi Gras Indian tradition of drumming and singing is one striking holdover of the Congo Square legacy. Similar traditions are found in the Caribbean, another area of African influence.

As a result, Louisiana retained a greater measure of the African musical and cultural ideas that were partially suppressed in the other slave states. Among these characteristics were polyrhythm: the simultaneous use of several different, yet-related rhythms, unified by a dominant rhythm known as the time line; syncopation; improvisation: the spontaneous creation of lyrics and/or instrumental parts; call-and-response: an interactive dialogue between a leader and a group of vocalists and/or instrumentalists; emotional intensity; the use of the human voice as a solo instrument, rather than to simply tell a story with lyrics; and the use of bent, slurred, or deliberately-distorted notes. All of these traits were prominent in the origination of the music that came to be known as jazz, which began to evolve after the Civil War.

Long before jazz emerged, however, these same African ideas appeared in earlier genres. By the early 19th century, several closely related styles were prevalent among the nation's large slave population. In retrospect they are collectively known as ante-bellum music. These Latin words mean "before the war," and refer to the Civil War. Several styles made up ante-bellum music. Work songs were chanted and sung by laborers who kept time with such tools as axes or hoes. Field hollers were spontaneously created vocal solos that commented on and communicated about personal or community conditions, recalling the West African tradition of griot singers. The individual singing of the field hollers also emerged in industrial settings, such as "calling the cotton press," and in such urban settings as the "cries" of street vendors who would announce their wares to the public. In the mid-1990s the street-crier tradition could still be heard in New Orleans. Field hollers gave rise to the group-singing format of the work songs, which employed call-and-response between a leader and work gang in setting the pace and rhythm for physical labor. In some cases this rhythm was enhanced by work implements such as hoes, or axes. Some work song lyrics were spontaneously improvised, while others were rooted deep in tradition and sung from memory.

Spirituals reflected the large-scale conversion of the slaves to Christianity, although these songs' religious lyrics often took on secret, double meanings that provided information for escapees. Another form of ante-bellum religious music was the ring shout, named for ceremonies where a standing circle of people sang or shouted with intense fervor, accompanying themselves with percussive hand-clapping and foot-stomping. In addition to these vocally oriented styles, ante-bellum music was played on such instruments as the banjo—which originated in West Africa—as well as the guitar, harmonica, and fiddle, among others.

During the latter half of the 19th century there was considerable interchange between ante-bellum music and European concepts of standardized song structure. This synthesis created the sounds that are broadly classified today as blues and gospel music. Ante-bellum music has all but disappeared (fortunately, it was thoroughly documented in folkloric field recordings), but blues and gospel have thrived for more than a century and half, changing and adapting with the times. What's more, these bedrock genres have exerted profound influence upon rockabilly and rhythm & blues and soul music, and commercial country music, as well as jazz.

Many New Orleans jazz songs use the prevalent blues pattern of twelve-bar verses, one-four-five chord progressions, and A-A-B lyrics in which the first line is repeated for emphasis. Early jazz was also influenced by the emotional intensity of the ring-shouts. Nevertheless, the African-rooted element in jazz is only one of its key components. As a wealthy, cosmopolitan port city with strong ties to France and Spain and enclaves of immigrants from Italy, Germany, and the British Isles, New Orleans was rich in European musical traditions. Orchestral concerts, recitals, musicals, and operatic performances all flourished, as did military bands. One of America's first great classical composers, Louis Moreau Gottschalk, hailed from New Orleans, and based many of his intricate works on regional folk tradition. In addition, there was great demand for bands to play popular music of the day at parties, picnics, political rallies, and the like.

Although New Orleans was strictly segregated, especially during Reconstruction, many whites-only events featured entertainment by black musicians, who also played at functions in the black community. Essentially, jazz evolved from the interaction of African aesthetics with European concepts of standardized musical notation and the expression of African aesthetics on European instruments. Another significant influence was the rhythmic patterns brought by immigrants from Cuba and Haiti. This aspect of jazz reflects Louisiana's status as the northern frontier of Caribbean culture, which is also reflected in culinary traditions, folk architecture, and belief systems such as voodoo.

The first renowned jazz New Orleans musician was cornetist Charles "Buddy" Bolden, who began performing publicly in 1895. No recordings of Bolden are known to exist, but his powerful playing made a huge impression on the next generation of New Orleans jazz musicians, including cornetist/ trumpeter Louis Armstrong, clarinetist Sidney Bechet, and pianist Jelly Roll Morton, who rose to prominence a quarter-century later. The recordings of these talented figures and their colleagues define the classic New Orleans jazz sound. Appreciation of their work has increased significantly during the past decade, thanks to attention from celebrated young admirers such as Wynton Marsalis. The Marsalis Family is also actively involved in contemporary and progressive jazz and their presence is one indicator of the extensive modern jazz scene that exists today in New Orleans.

While many early jazz musicians were African-American, other ethnic groups in the city also contributed to this exciting new multi-cultural music. There was considerable input from Latin Americans, as well as from New Orleans' large Italian-American community. Led by trumpeter Nick LaRocca, the Original Dixieland Jass Band [their spelling] made some of the very first jazz recordings in 1917. Trumpeter and singer Louis Prima, whose career spanned the 1930s to the 1970s, became one of America's most popular entertainers. Prima's vast repertoire included jazz, blues, and swing, with vocals in English, along with traditional Italian material played with jazz arrangements and sung in Italian. Prima's music has always remained popular in his native New Orleans, and a recent resurgence of interest in swing and big bands has brought his work back to national prominence. Today, the term dixieland is sometimes used to refer to older traditional New Orleans jazz styles; in some circles, it specifically denotes white jazz musicians such as Pete Fountain and the late Al Hirt. As with most terminology, though, dixieland has many meanings.

New Orleans jazz is played on a variety of instruments. Brass—specifically the trumpet, cornet, and trombone—is prominently featured, and so is the tuba among bands that parade. Woodwinds such as the clarinet and saxophone are equally essential. The piano is a vital instrument among traditional jazz groups that play in a stationary location rather than parading on the street, and the acoustic guitar and/or four-string banjo may also be present. Bass, either electric or acoustic, fills the same rhythmic function as the tuba does in parade bands. In similar fashion, groups performing in stationary, non-moving venues use a full drum kit, sitting down, while parading groups hire a bass drummer and one or more snare drummers who play while they walk. Miscellaneous percussion instruments may also appear in both settings. Modern jazz groups may also feature the vibraphone, synthesizers, various electric keyboards, and the electric guitar. Vocalists are prominent in both the traditional and modern jazz schools.

Rhythm & blues is another genre that saw crucial developments in New Orleans, beginning in the late 1940s and continuing to the present day. R&B, as it is commonly known, is a hybrid of traditional African-American blues and jazz with various mainstream sources. The instrumentation used by stationary, traditional jazz bands, as discussed above, also applies to many R&B groups, especially those that recorded during between the 1940s and 1960s. R&B employs a wider variety of song structures and chord progressions than traditional blues, and, like jazz, it often features complex arrangements that may be unique to one particular song. Also, while many R&B songs have strong traditional roots, they differ from traditional music in that they are created by professional intent on scoring a hit and making money.

The late 1940s through the early 1960s are often referred to as the Golden Age of New Orleans R&B, thanks to the wealth of great records by Fats Domino, Smiley Lewis, Professor Longhair, Ernie K-Doe, Irma Thomas, Clarence "Frogman" Henry, Frankie Ford, and many others. Many of these records were national and even global hits, while some were popular in the Gulf South only. The 1970s saw the emergence of such fine New Orleans R&B artists as Dr. John and the Neville Brothers. Today the torch is carried by the likes of pianist and singer Davell Crawford. New Orleans rap stars such as Mystikal and Master P also have links to this legacy.

In addition, the huge success of Fats Domino inspired many major record companies based in New York or Los Angeles to bring their top artists to New Orleans' studios during the 1950s. The theory was that accompaniment by the city's talented studio musicians would increase the chance of a hit, and such thinking often proved to be quite on-target. Little Richard, a frantic singing pianist and R&B/rock icon, recorded such classics as "Tutti Frutti" and "Long Tall Sally" in New Orleans, accompanied by many of the musicians who appeared on Domino's records. Many of these session players were quite accomplished jazz musicians as well. Other R&B stars that experienced similar success included Etta James, Big Joe Turner, and Patti LaBelle. In the 1970s, ex-Beatle Paul McCartney worked with the renowned R&B producer, Allen Toussaint, in New Orleans, resulting in the hit "Listen To What The Man Said."

A fascinating blend of R&B, ante-bellum music, and Afro-Caribbean rhythms can be heard in New Orleans' Mardi Gras "Indian" tradition. These "Indians" are not Native Americans, however, but rather groups of African-American men who parade, chant, and drum on Mardi Gras Day, dressed in elaborate hand-sewn costumes with beadwork and plumes. The intricate designs of these costumes often are inspired by Native American culture and costumes. The "Indians" do not practice elaborate dance steps primarily because their costumes are extremely heavy and cumbersome. But the throngs of people who attend their parades often engage in improvised solo dance steps from the "second-line" tradition that is also found at parades and funeral processions that feature brass bands playing New Orleans jazz.

The origins of the Mardi Gras Indian tradition are often debated. Markedly similar ceremonies in terms of clothing and music take place throughout the Caribbean. There are many Mardi Gras Indian groups, known as "tribes," in New Orleans. Several, including Bo Dollis and the Wild Magnolias, and Monk Boudreaux and the Golden Eagles have blended their chants and drumming with contemporary R&B instrumentation and enjoyed commercial success. Other tribes use nothing but percussive instruments such as tambourines, cowbells, hand-held drums, or even scrap metal. Some tribes maintain great secrecy about their traditions and discourage outsiders from making recordings or taking photographs.

Baton Rouge

Baton Rouge, Louisiana's capital city, straddles the cultural border between French/African/Catholic South Louisiana and British/African/Protestant North. Baton Rouge has an extensive history as a center of blues activity. Elements of ante-bellum music and rural blues have shaped the Baton Rouge sound, as heard on the records of such artists as the late acoustic guitar duo Silas Hogan and Arthur "Guitar" Kelley. These traits include songs where successive verses are not always the same length, and songs where the lyrics and tempo might differ greatly from one performance to the next. These elements reflect the presence of a large community of people from rural areas who have moved to Baton Rouge in search of industrial jobs that pay more than agricultural labor. Instrumentation varies in the rural blues, and might consist solely of a lone acoustic guitar, as heard on the great recordings of Robert Pete Williams. Some rural stylists formed duos, such as Kelley and Hogan, while others formed bands that might feature piano, harmonica, electric guitar, fiddle, bass, and drums, in varying combinations.

During the 1960s, a singing harmonica player from Baton Rouge named Slim Harpo scored an unlikely hit on the national pop charts with the blues song "Baby, Scratch My Back." (Harpo's real name was James Moore; his nickname was a reference to the "mouth harp," as the harmonica is also known.) Harpo's style had a rural tinge but used conventional uniform song structure. Beyond his success in America, Harpo influenced a young generation of British blues imitators such as The Rolling Stones. In a curious pattern of cultural exchange, these British musicians helped introduce young, white American audiences to African-American blues. In addition to Slim Harpo, who passed away in 1970, guitarist Buddy Guy is the most prominent artist to emerge from the Baton Rouge blues scene. A native of Pointe Coupee Parish, Guy learned his trade in Louisiana's capital city and then moved to Chicago, where his career took off and where he headlines at his own nightclub today. But Baton Rouge is still home to a varied and active blues community. Elder statesmen include pianist Henry Gray, guitarist Tabby Thomas, and harmonicist Raful Neal. Thomas' son, Chris Thomas King, is a popular young blues modernist, while several of Raful Neal's children are carrying both a family and civic tradition. These groups are apt to feature electric guitar and keyboards, backed by rhythm sections of bass and drums; harmonica, solo horns, and/or horn sections may appear as well. Baton Rouge also nurtures an active swamp pop and rock scene, represented by such nationally-prominent figures as Johnny Rivers, John Fred and the Playboys, and Louisiana's LeRoux.

South Louisiana

Fifty miles west of Baton Rouge, across the Atchafalaya Basin, lies the prairie homeland of Cajun music and zydeco, which extends westward into east Texas. Cajun and zydeco (pronounced ZY-duh-coe) are the exuberant dance-music genres of Southwest Louisiana's French-speaking people. "Creole" is a controversial word in Louisiana, involving a complex web of racial and socio-economic identity. In this essay, "Creole" and/or "black Creole" refer to the members of Southwest Louisiana's black community who speak French or have ancestors who did. These are the people who created zydeco. "Cajun" refers to their white, French-speaking neighbors. This definition of "Creole" is a subjective usage, and it does not endorse or dismiss other interpretations. Many people, who call themselves "Creole," by whatever definition, become angry when the name is used by others whom they consider unworthy or unqualified. The "Creole" debate is likely to rage on, unresolved, in Louisiana.

The term "Cajun" is a shortened form of "Acadian." The Acadians were residents of Acadie, a prosperous French colony in what is now Nova Scotia, in eastern Canada. Britain took control of Acadie in 1713 and deported the Acadians in 1755. Many Acadian exiles eventually settled on the west side of the Atchafalaya Basin. This area remained quite isolated until the early 20th century, when the oil industry brought in mainstream American culture and the English language. Even so, there are still some half a million people who speak Cajun and Creole French, although almost all speak English, too. Cajun music and zydeco are important expressions of these cultural and linguistic legacies.

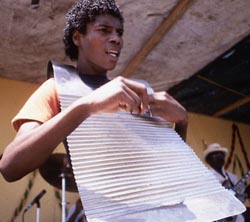

Zydeco is a rich stylistic hybrid with a core of Afro-Caribbean rhythms, Creole folk music, blues, and Cajun music, plus other elements that vary from band to band. Rock, country, rhythm & blues, reggae, and rap music may all factor in. Traditionally, zydeco is sung in Creole French, and its lyrics are often improvised. It is absolutely not intended for passive listening. As accordionist Clifton Chenier, one of zydeco's leading figures, stated: "If you know how to dance, then you can dance behind someone beating on an old gallon bucket. But if you can't dance to zydeco, you can't dance, period." Accordingly, dancing is an important component of all zydeco and Cajun music performances.

The word "zydeco" is often explained as originating in the French phrase "les haricots" (pronounced lay-ZAH-ree-coe). The phrase "les haricots sont pas salés" appears frequently in Creole folk music. Some cultural activists feel that "zarico" would be a more appropriate spelling, although "zydeco" has been the accepted standard since the early 1960s; before then, various spellings were used, and the music was also referred to by such names as "French music" and "la-la." There are also theories that the word may have African, rather than French roots. In any case, "les haricots sont pas salés" literally means, "the snap-beans are not salty." It is also a metaphor for hard times—times that are so hard, in fact, that people cannot afford salt pork to season their food.

This phrase is heard in many traditional Creole songs, starting with an ante-bellum style known as juré singing. Juré comes from the French jurer - to testify, or swear—and is closely related to the African-American ringshout. Similarly, there was no instrumental accompaniment in juré; hands and feet pounded out urgent rhythms.

Some stunning examples of juré music were recorded by folklorist Alan Lomax for the Library of Congress in 1934. Lomax called juré "the most African sound I found in America." Besides containing riveting performances, these recordings mark the first documentation of the exclamation "les haricots sont pas salés." This phrase gradually came to have several separate, yet related new meanings: the title of a song, "Zydeco sont pas salés;" the name of the musical genre represented by that song; the social gatherings where such music was played; and the dance steps and the act of dancing that the music inspired. These overlapping meanings can be confusing. As journalist Susan Orlean pointed out that "[i]n theory, this meant you could zydeco to zydeco at the zydeco."

Beginning in the late 1940s, Clifton Chenier took the traditional sources of juré and blues, blended them with the latest R&B hits of his day by artists such as Fats Domino and Big Joe Turner and adapted the arrangements to his accordion. In doing so, he set the standards that have defined zydeco during the fifty years that have followed. Today's popular artists including Stanley "Buckwheat" Dural, Geno Delafose, Nathan Williams, and Sean Ardoin, are all influenced by Chenier's music. In addition, they follow his forward-thinking example by adapting various popular styles to zydeco. Sean Ardoin, a fourth generation Creole/zydeco musician, has managed to successfully incorporate rap and hip-hop into this mixture.

The sound known today as zydeco did not emerge until the late 1940s, while Cajun music already existed when commercial recording became a thriving industry in the 1920s. At the time, however, most Cajun musicians referred to what they played as "French music"; "Cajun music": as a genre-defining term did not emerge until after World War II. Accordingly, there is more extensive and older documentation of Cajun music, beginning with the groundbreaking recordings of musicians such as Joe Falcon, and Amedee Breaux. In the early 1930s, The Hackberry Ramblers ushered in a blend of Cajun music with country and various mainstream popular styles, in a string-band format that temporarily set the accordion aside. After World War II the accordion came roaring back thanks to such great stylists as Iry LeJeune. The 1960s were a slow time for both Cajun music and zydeco, as the conservative mood of the day discouraged expressions of regional culture. Both genres were in danger of dying out, despite the efforts of activist musicians such as Dewey Balfa.

By the late 1970s, however, Cajuns and Creoles began to rediscover and celebrate the unique culture of South Louisiana, in which music figures so prominently. Young bands such as BeauSoleil typified this new attitude, while old masters such as Dennis McGee and Sady Courville enjoyed second, late-blooming careers. Today Cajun music and zydeco enjoy an unprecedented level of acceptance, both at home and abroad.

The dominant instrument in both zydeco and Cajun music is a relative newcomer to Louisiana—the accordion. Accordions were brought to America from Germany and Austria in the mid-19th century, and peddlers began selling them in South Louisiana after the Civil War. Before that time, fiddles and guitars were prominent, along with unaccompanied ballads. Many of these songs could be traced back to Acadie, and ultimately to medieval France.

Accordions caught on quickly because they were durable, and worked well with a wide variety of music. Most significantly, the air-driven accordion could cut through the noise of a lively dancing crowd at a time when electronic amplification did not exist. Itinerant vendors also introduced the accordion into Texas, where it was welcomed in German and Czech communities and then adapted by Mexican-Americans to create the popular sound now known as "norteno" or "conjunto."

Two types of accordions are used in South Louisiana. Chromatic accordions, also known as piano accordions, include the half-steps, as represented by the black-and-white key configuration found on pianos. This allows usage of the "blue notes" within any given key: the flatted third, flatted fifth, and flatted seventh. Diatonic accordions contain only the whole notes of a scale, although they can be built as "triple-row" models that are playable in three different keys. Until the 1980s, chromatic accordions were only heard in the zydeco bands led by more sophisticated players such as Clifton Chenier and Stanley "Buckwheat" Dural. Other zydeco artists such as Boozoo Chavis used diatonic instruments, as did almost all Cajun accordionists.

These distinctions have blurred in recent years, though, as Cajun music and zydeco have exchanged many ideas. For example, the frottoir or rub board was once found only in zydeco bands. This percussive instrument consists of a corrugated metal vest that hangs from the player's shoulders and is scraped against the chest with spoons or metal bottle openers. The rasping sound that results is thought to reflect the influence of both African and Native American traditions. Today it is not unusual to find younger, more diverse Cajun bands that use the frottoir to enrich the rhythmic texture of their music. (One of the first to do this was accordionist Wayne Toups, who called both his music and his band "Zyde-Cajun.") Conversely, the triangle or 'tit fer, once a common percussion item in acoustic Cajun bands, is heard less frequently. Most contemporary Cajun and zydeco bands use bass and drums. Guitars, either acoustic or electric, are also common.

In addition to the Acadian legacy of fiddle tunes and unaccompanied ballads, Cajun music has a long history of interaction with British-American country music. The Hank Williams song "Jambalaya (On the Bayou)," for instance, uses the melody of an old Cajun song known both as "Grand Texas" and "L'anse Couche-Couche." This exchange of ideas works both ways; a Cajun favorite, "The Belizaire Waltz," uses the melody to Roy Acuff's country-gospel hit, "The Precious Jewel." In addition, the fiddle remains prominent in Cajun music, although it has all but faded from Creole music and zydeco, and many Cajun bands also feature the pedal-steel guitar. These common factors have led some country-music historians to dismiss Cajun music as nothing more than country sung in French, which is not correct.

Cajun music and zydeco have also contributed to a South Louisiana genre known as "swamp pop"—a hybrid of pop, rock, and rhythm & blues recorded by Cajun and Creole musicians primarily during the 1950s and 1960s. In terms of structure and instrumentation, swamp pop is virtually identical to the era's pop, rock, and R&B found in other parts of the country. Accordions are rare in swamp pop, which favors typical R&B instrumentation. French lyrics are rare, as well. Instead, swamp pop's regional identity comes from a soulful, emotional vocal style that has strong roots in zydeco and Cajun music.

Several swamp pop songs have become national hits. "Sea of Love," a 1959 recording by Phil Phillips, was the most successful among these, outside of Louisiana. But songs such as "Mathilda" by Cookie and the Cupcakes, "Irene" by Guitar Gable, and Rod Bernard's "This Should Go On Forever" are timeless classics along the Gulf Coast. Swamp pop is also notable because, during an era of strict segregation, it was one of the first genres where black and white musicians recorded together, although they could not share the bandstand at public performances. Many zydeco and Cajun artists, such as the late Rockin' Sidney and Belton Richard, have pursued dual careers in swamp pop, and retain it in their repertoires. There is also a dedicated core of Creole and Cajun musicians, such as Little Alfred and Sonny Bourg, who focus on swamp pop exclusively.

Elements of swamp pop, Cajun music, zydeco and blues are all present in the contemporary-country song writing of Lucinda Williams. Williams is a Lake Charles native and former resident of both Lafayette and New Orleans; she is currently based in Los Angeles. Her music reveals the lyrical influence of Hank Williams (no relation) alongside such Southern literary figures as Flannery O'Connor and Cormac McCarthy. Just as the South Louisiana landscape has inspired such great painters as Elemore Morgan, Jr., the cultural landscape inspires fine contemporary lyricists who base their work in traditional music. Contemporary country uses a wide variety of instruments. Acoustic, electric, and pedal-steel guitars are all prominent as are acoustic and electric keyboards, fiddles, and, on occasion, the harmonica. Solo horns or horn sections may also be present, more than in traditional country.

North Louisiana

North Louisiana is populated primarily by English-speaking Protestant British-Americans (also referred to as British Americans) and African Americans. North Louisiana includes all areas north of the "French triangle" (see map.) In cultural terms, and for the sake of discussion in this essay, it also includes the Florida Parishes. The traditional musical British-American genres that characterize North Louisiana are ballads and lullabies, old-time country and string bands, bluegrass, and country-western. Gospel is prominent in both the British-American and African-American communities, while rockabilly represents a synthesis of the two cultures, as discussed in more detail below.

Country music is rooted in such British folk traditions as ballads, folk songs, and fiddle tunes such as reels, airs, jigs, breakdowns, and the like. In remote parts of America, especially southern Appalachia, these traditions survived for generations, and were largely unchanged to a remarkable extent. Even so, songs that were played on the fiddle in Britain were adapted to instruments such as the banjo and guitar, which have African and Spanish origins, respectively. With westward expansion, this legacy of British-rooted New World music came to the predominately Protestant reaches of North Louisiana, including the Florida Parishes, and it lingers there today in several different forms.

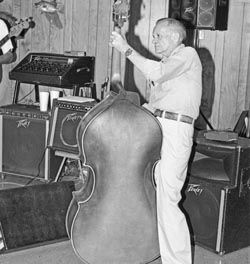

Old-time country music is played on acoustic instruments such as the fiddle, guitar, banjo, mandolin, Dobro, and the acoustic bass, which is used to keep time. This format also characterizes the closely-related string-band tradition. Old-time country has a core of British tradition but also incorporates blues and published popular songs from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Old-time country spawned bluegrass, a more modern acoustic genre with faster, more aggressive rhythms, sophisticated solo technique, and a broader range of stylistic influences, including jazz. In fact, many popular bluegrass songs can also be found in such other traditional genres as New Orleans jazz.

Bluegrass is most commonly associated with Appalachia and is a relatively recent import to Louisiana, more so through records and radio rather than longstanding folk-music tradition. Bluegrass has an active following throughout the state. In addition to North Louisiana, bluegrass is popular in the Florida Parishes that lie east of Baton Rouge and north of New Orleans. The principal instruments in bluegrass include five-string banjo, mandolin, guitar, fiddle, the acoustic bass, and the Dobro. The Dobro is a guitar that is held horizontally when played; most guitars are held vertically, or parallel to the player's body. "Dobro" is a registered brand name that, much like "Xerox," has evolved into a generic term. Both old-time country and bluegrass are often played at rural festivals. The organizers of many such events pride themselves in maintaining a wholesome family environment in which alcohol is forbidden.

Similarly, close-harmony singing is a vocal-duet style that comes from old-time country and is also heard in bluegrass. In Louisiana, this style is expertly practiced by The Whitstein Brothers from Pineville in Rapides Parish. Close-harmony singing has also exerted great influence on rock and pop music. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, a close-harmony duo known as The Everly Brothers, from Kentucky, took a folk-roots approach and applied it to pop and rock with great commercial success. The Everly Brothers were idolized by The Beatles, who imitated their close-harmony sound, ironically bringing a British style back to Britain, full circle.

Besides bluegrass, another country style with distinct jazz influences is the hybrid known as western swing. This style evolved during the 1930s, disproving the stereotype that jazz and country are mutually exclusive. In fact, country music's first star, Jimmie Rodgers, recorded with Louis Armstrong. Western swing artists such as Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys greatly influenced the North Louisiana country scene as well as Cajun music, through bands such as The Hackberry Ramblers. Western swing was also the first country genre to use amplification and feature such instruments as the electric guitar; as such, it was an important precursor to rockabilly, which emerged some twenty years later.

By the early 1950s, electrified instruments dominated such popular country styles as honky-tonk. This instrumentation was fairly simple, including electric guitar, lap-steel guitars and pedal-steel guitars, fiddle, and acoustic bass; full rhythm sections including drums were used by some bands but not all.

There is a common misconception that commercial country music, as opposed to field recordings made by folklorists, maintains strong connections with the British folk roots discussed above. Country has been commercially marketed since the 1920s, interacting with a wealth of other genres and developing new traditions within itself, such as the honky-tonk style. British folk roots are still a factor, but much less significantly than in the isolated rural world of the 19th and early 20th centuries. As commercial country grows increasingly mainstream; however, there are periodic back-to-basics movements in which older styles are re-emphasized, including those with strong British roots.

Shreveport, in Louisiana's northwest corner, is a vitally important city in the history of American traditional music. The great blues guitarist Huddie Ledbetter, also known as Leadbelly, honed his performance skills in Shreveport's blues clubs during the 1920s. Ledbetter was first recorded by Library of Congress folklorists John and Alan Lomax. He went on to become a popular and influential entertainer who introduced rural blues and ante-bellum music to urban audiences around the nation. So did guitarist Jesse Thomas, who made his first recordings in 1929 and remained active on the local scene until 1995. Successive generations of Shreveport blues talent have continually emerged over the years; contemporary artists include such singers as Dorothy Prime, young guitarist Kenny Wayne Shepherd, and the blues-rock band The Bluebirds.

Much early blues in Shreveport was performed on acoustic instruments such as the guitar, harmonica, and piano. Leadbelly played the twelve-string guitar and used it to give his music a rhythmic drive that would rival most full electric bands. Contemporary blues, soul, and R&B in Shreveport and throughout North Louisiana tends to favor such instruments as bass, drums, electric guitar, various types of keyboards, and saxophones and/or horn sections.

Shreveport has also played a pivotal role in country music. From 1948 until the 1960s, a live radio program known as The Louisiana Hayride was broadcast on Saturday nights from the Shreveport Municipal Auditorium. The Louisiana Hayride reached a broad national audience thanks to its strong radio signal on station KWKH. The program created another nationally-recognized venue for country music similar to that of the Grand Ole Opry and the WLS Barn Dance. The Louisiana Hayride hosted such talent as Johnny Cash, Jim Reeves, Louisiana's own Webb Pierce, and Hank Williams. Country-music instrumentation, at this time, was fairly simple. Electric guitar, lap-steel guitar and pedal-steel guitar, bass, and fiddle were prominent; full rhythm sections including drums were used by some bands, but not all.

In addition, The Louisiana Hayride helped nurture a new, multi-cultural style known as rockabilly, by hiring a then-obscure young singer named Elvis Presley, who performed on the Hayride between 1954 and 1956. Rockabilly combined elements of British-American country music, especially the jazz-influenced and electric guitar-oriented sounds of western swing, with African-American blues and R&B, and the gospel fervor of both cultures. One of the most important originators of rockabilly was a wild pianist and singer named Jerry Lee Lewis, from Ferriday in Concordia Parish. He emerged in the mid-1950s with such passionate recordings as "Great Balls of Fire" and "Whole Lotta Shakin' Goin' On."

Lewis' dynamic performances were released by Sun Records, the Memphis-based company that also launched the career of Elvis Presley. Lewis has continued to record and tour prolifically ever since, inspiring future generations of rock-and-rollers around the world. Rockabilly often features piano, electric guitar, drums, and bass. Acoustic bass is regarded by many as an essential element of the authentic rockabilly sound.

Although The Louisiana Hayride ended in 1970, its legacy lingers on. Maggie Lewis Warwick, a songwriter and entrepreneur who performed on the Hayride, remains active in Shreveport. So does guitarist James Burton, who returned home after years in Los Angeles as one of the nation's top session musicians.

Another North Louisiana city, Monroe, was the home base of the late country singer Webb Pierce who, along with Hank Williams and George Jones, helped developed the late 1940s country style that is known today as "honky-tonk." The honky-tonk style favored sentimental, emotional lyrics that were often sung in distinctly rural accents. Pierce's numerous honky-tonk hits included "Wondering, Wondering," "Back Street Affair," "There Stands The Glass" and "Why, Baby, Why." Honky-tonk country favored simple instrumentation that focused attention on the vocals. Electric guitar was often used as rhythm instrument, instead of bass and drums, with pedal-steel guitars and fiddles providing solos.

The rural communities of North Louisiana have a long history of nurturing various types of traditional country music. The late Brownie Ford, an Oklahoma native who settled in Hebert in Caldwell Parish, was a singer of British ballads and 19th century cowboy ballads. Ford was also an engaging storyteller, and a master of many craft skills. Ford's diverse repertoire also included honky-tonk country and rockabilly, and he was equally at home accompanying himself on solo acoustic guitar or playing with a full band.

Governor Jimmie Davis, of Quitman in Jackson Parish, used his own talent as a country musician to help him win election as Louisiana's governor. Davis' first records, made in 1929, were heavily blues-influenced. He is best known for the song "You Are My Sunshine." Unlike the honky-tonk singers, Davis had a smooth style and no obvious rural accent. After leaving office he remained active as a performer.

Currently, The Cox Family, an internationally prominent group from Cotton Valley in Webster Parish, is considered Louisiana's most popular bluegrass band. The Cox Family's fame increased significantly when they appeared and performed in the film, O, Brother, Where Art Thou?. However, this group reportedly refers to themselves as an old-time country and gospel band. Regardless of the group's objections to the bluegrass label, the Cox Family's music is marketed as bluegrass, and it is in this category that they have won Grammy awards. Such disagreements over terminology indicate the imprecise and subjective nature of musical categories.

Finally, the religious themes of gospel music resonate throughout Louisiana, among blacks and whites alike, in both the predominately Protestant north and the predominately Catholic south. White gospel groups are rooted in British-American musical traditions, and tend to represent fundamentalist Protestant denominations. Black gospel, heard in Catholic as well as Protestant churches, evolved from the African-rooted ante-bellum traditions of spirituals and ring-shouts. It also bears the imprint of a late 19th-century style known as jubilee singing, which incorporated various European elements.

Louisiana's African-American gospel traditions encompass a range of styles. Solo singers such as the late Mahalia Jackson, of New Orleans, inspired listeners with their religious fervor and pure vocal power. Jackson used many time-honored African-American musical traits—including call-and-response, syncopation, bent and slurred notes, growls, and screams—all of which are also heard in blues.

The classic gospel quartet sound combines these effects with elements of jubilee singing. This approach makes exquisite use of four-part harmonies, sung in different registers that maximize the effect of the contrasting voices. The quartet sound, as practiced by distinguished groups such as Shreveport's Ever Ready Gospel Singers and The Zion Travelers from Baton Rouge, has also exerted great influence on secular R&B. Many quartets perform a cappella, with no instrumental accompaniment; others use bass and drums, electric guitar, and keyboards. This instrumentation is also used to back up rousing gospel choirs that may include dozens of singers.

One of the most striking manifestations of African-American gospel music in North Louisiana is Easter Rock—a ritual ceremony using traditional folk movement and folk music. It is still held in the Original True Light Baptist Church in Winnsboro, in Franklin Parish. Dating back to ante-bellum times in the Louisiana Delta region, but relatively unknown outside the area, the Easter Rock service has been performed for generations on the Saturday evening before Easter Sunday. As the congregation sings hymns, participants take rhythmic, reverberating steps from side to side while moving in a circle around a table in the church aisle. At the end of the rock ritual, the food on the tables is served to the congregation. In the past, the Easter Rock service traditionally lasted until midnight, but today it often ends earlier because members attend a sunrise church service on Easter morning.

Another striking folk-practice in Louisiana gospel music—both African-American and British-American—is shape-note singing. This a cappella style, found in some Protestant congregations, is based on a simplified system of musical notation. Instead of reading music by the placement of the notes on the staff, shape-note singers sound out the tune by reading the shapes of the notes. There are two systems of shaped notation. The older Sacred Harp system, named after a book by that name, uses only four syllables (fa, sol, la, and mi) in the musical scale, with each of these syllables having its own shape. The newer seven-note system (using do, re, mi, fa, sol, la, ti) is more commonly used in North Louisiana today.

This essay covers the dominant regional music traditions of Louisiana, but there are many other cultural, ethnic, and religious communities with distinct music traditions. These include Hungarians, Czechs, Irish, Italians, German, Yugoslavs, Jews, Filipinos, and more, along with recent immigrants from Latin America and Southeast Asia. Some documentation exists, but much remains to be done as we revel in the fact that be it Saturday night or Sunday morning, from Angie to Zwolle and all points between, Louisianans are never far from their treasured traditions of music.

Resources

For classroom resources: Louisiana Voices Educator's Guide. Unit II Classroom Applications of Fieldwork Basics includes lessons to bring artists into the classroom and Unit VI Louisiana's Musical Landscape explores Louisiana music and folk dance.