Splittin on the Grain: Folk Art in Clifton, Louisiana

Crafts From The "Back Days"

By Claude Medford

All human communities from times out of memory have created things which have made their individual lives easier. Pottery was made to cook in or to contain ceremonial or religious offerings; baskets were woven to carry things or to prepare food; cloth was woven to wear; houses were built to shelter mankind from ever-present nature. These things, among many others, which people have made become things of "art" and beauty when they are produced, not just for utility, but to the best of each individual's ability in order to enrich his or her life. When an individual excels in one particular art or craft, this product becomes something of value which the entire community can enjoy and admire. This beautiful object retains its function; it can still be used everyday. It is recognizable, even by strangers to the community, and because of its utility and beauty, the memory of it can be carried away to other communities to be copied. Knowledge grows and the world becomes larger.

In those times when the local community was the center of the world to most individuals, mankind depended upon himself to provide the necessities of life. He never thought that another community or another tribe could or should provide these necessities. It was believed that the passage of time would allow each individual to practice his necessary crafts, that each year brought an increase in wisdom, and at his death, the young people would have seen that in order to survive, their own abilities and knowledge should be on the increase from the wisdom gained from their old people. Knowledge and a sense of value were concepts that lived, were alive and never died.

When individuals began to leave their communities to earn wages in often distant factories, they left one at a time; then whole families left and finally people in swarms came to the city for, they hoped, a better life. The aged people left at home became valueless, useless yokes around the necks of their "progressive" children. Often, in anger, the knowledge and wisdom of these abandoned old people died with them; they did not wish to pass on what they knew to children who would not use it, or if they did use it, would profane ancient knowledge. With the passage of time, the children, in turn, became old, but because they had not kept alive proven knowledge and wisdom, they knew only their job at the factory, nothing else. Without wages they could not live and were in turn, "dumped" by their children in so-called "nursing" homes. Without knowledge, without a past of accumulated knowledge and talents, people now demand to be supported by distant communities, by unseen and unknown governments. They do not even know how to depend on knowledge, and people have become constant children and remain children without experience.

To quote John Collier, U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1933-1945, in his book On The Gleaming Way, he says, "We all know this white world: its concentration on externals, on "upward mobility," on conveniences and on meaningful sensation and material security: ... a world of no long dwelling with any deep ideas. This world takes for granted its own finality and omnipotence..." I quote Mr. Collier because these concepts themselves spell the ending of communities and traditional knowledge. People are no longer secure enough to depend on themselves. Like children, people now need someone to control, to direct, and to give purpose to their lives, even if this comes from so-called elected governments far away.

Traditional crafts are very difficult to revive or rejuvenate because the passage of time has erased their memory. Only the very old remember what was made in the time of their youth; most young people have never seen, heard, or thought of these things because of the events in recent years written above. People, nowdays, feel they are too busy, not patient enough, or have better things to do with their time.

The traditional attitude toward time has changed; time is now limited and in portions.

The community of Clifton, Louisiana, some 30 miles west of Alexandria, is a community of partial Native American descent born some 110 years ago. At its birth, in a time of much movement and confusion, groups and races from other communities from all over the South and the world joined the community and created something of great interest, a new community with knowledge and traditions from older, now dispersed communities. With knowledge of crafts and traditions coming from all over, typical crafts truly of Clifton, came into existence. These crafts flourished, were used daily and the knowledge of their construction was passed on, until, finally, with the approach of "modern" concepts, they fell into disuse and were remembered only by the very old who were usually not physically able to continue making traditional crafts. In the 1970s, present residents of Clifton began to think of and to remember the craft tradition which was truly their own. Craft traditions from nearby communities were also learned (this was true in the past as well) and once again people are making baskets, carving wood, braiding yucca into whips; are thinking of traditional smoking pipes and containers of locally gathered clay, and of finely tanned skins. The problem that these now active craftspeople of Clifton face is the regaining of the respect of the youth of the community. Will the young people learn again to depend on themselves? Will these crafts coming alive again have the values of traditional community times? If these crafts are passed to the young people, will they try to excel in them? As in the past, only the passage of time will reveal the answers to these questions asked by the craft leaders of the community of Clifton, Louisiana.

Pieces and Patches -- A Whole From Many Parts

By H.F. Gregory

The piney woods of western Louisiana were a refuge for people of all kinds. By the late 18th century, British Americans, Choctaw, and other eastern Indians fleeing English expansion, and mixed-blood people uncomfortable in the white dominated southern caste system, seeking solace from poverty and the rigidity of caste, moved there.

Wherever these people came to interact with one another, the ebb and tide of culture mixed their material culture, language, and, on occasion, genes. Each culture had, over the generations, built a unique set of traditional responses to the southern environment. All the wild and domesticated plants and animals were used to make the communities autonomous.

By 1900 many of the adaptations which had been developing for at least a century and a half were jarred by the advent of the lumber industry. It swept across the landscape, stripping the vast stands of timber, offering a wave of affluence and then total poverty. New people, with new ways and "new technology," swept in and moved out as the sawmills "cut out." Left in a sea of pine stumps, on essentially barren lands, the people -- of all ethnic groups -- again fell back on old ways and brought back their traditional responses to survive.

Clifton settlement is a community whose material culture clearly reflects all these influences. The shared experience of sawmill labor camps was a catalyst, and poverty after the mills closed was the final ingredient for the creation of a unique material culture.

Seeking "roots" for material culture is somewhat futile as an historical exercise, but it is possible to chart the history of social contact.

At Clifton some cultural "markers" can be identified. Obviously many cultures left pieces there along what has always been an important road south and west.

Quilts are made by piecing strips of scrap cloth together into patterns with standard Anglo-Saxon names (Light and Shadow and Log Cabin), but unique asymmetrical patterns are common. Many ascribe such quilts to an Afro-American source, but many southern Indians also made such unique products and by the same techniques.

White oak splint basketry is made by virtually every traditional community in the South: Whites, Indians, and Blacks. Its origin at Clifton is diffuse, but the shapes (cotton baskets and egg baskets) are traditional. Surviving basketmakers who exchanged baskets for products in the plantation area along Bayou Rapides are still amazed to learn that what was once a subsistence trade has moved into the realm of commercial art.

Deerskin tanning, certainly an Indian tradition, developed in prehistoric times. However, the use of metal-bladed beaming tools (albeit homemade) clearly date to their widespread appearance in Spanish and English colonial times, a marker for the development of the deerskin trade. Still, hide tanning and smoking remained Indian. The whole process has remained in only a few places in the South. All documented cases of survival are in Choctaw communities located in cut-over pinelands.

At Clifton the process was reinforced by the coming of the timber industry. Deerskin and goatskins were tanned and sold to the muleskinners, not to make clothes or shoes as in Indian times, or cheap hats as in colonial times, but to cut into strips and strings for whip crackers and saddle repair! Functionally, the process produced an equally good product for all three cultural needs.

Carved wooden bowls are other products which reflect the possibility of multiple cultural roots. Wood carving was British American, Indian, and African. The Tupelo or Black Gum bowls made at Clifton were once famous and are still treasured household items. The form at Clifton is basically that of a colonial "tray" or "trencher," clearly European in origin. The technique of burning and scraping out the bowl's interior is clearly Indian!

Other items like wooden spoons, goose quill whistles, turkey tail and wing fans, gourd birdhouses and containers show equally mixed character.The gourd birdhouses are ubiquitous all across the southern highlands from Louisiana to the Tidewater. However, at Clifton, just as in Virginia, people cut square doors on their "bottle gourd" houses, an Indian trait rarely seen outside those two areas.

Gourd dippers, on the other hand, are made in purely Anglo-Saxon ways and clearly contrast with Louisiana Indian techniques.

What is unique about the material culture at Clifton is not, however, its diverse cultural origins; it shares these with a multitude of other communities. Rather Clifton has preserved and passed on such traditions with skill and pride. Clearly, the exigencies of culture change have been met, but, where and when old ways could be integrated and used, the old ways have been preserved. In spite of such problems, Clifton folks have kept their act together. Their material culture is a clear reflection of their efforts to survive and remain a community in the fullest sense of the word.

Folk Art In The Clifton Community

By Shari Miller and Miriam Rich

The Clifton community, a rural settlement of approximately 300 people in Rapides Parish, Louisiana, appears to have formed in the mid-1800s when Choctaws who had lived in the area since the early part of the century, or who had migrated from the Sabine in the 1860s and 1870s, intermarried with second generation immigrants from the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia.

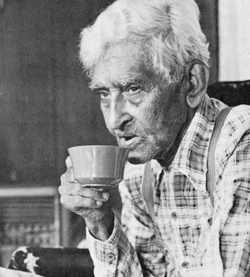

This settlement, which finally gained state recognition as an Indian community in 1979, has a rich tradition of Indian and Southern rural folk arts. As one elderly member of the community said, "Back in the old days, people made everything they could think of and tried to make that what they couldn't think of." Before the arrival of the lumber industry, jobs were scarce and community members supplemented their farm income by selling baskets, tanned hides, and bread trays to local whites. They also made many items for their own home use since manufactured products were few and expensive.

At Clifton, craft knowledge was not learned through books or classes; parents passed it on to their children. Though today many of the community's folk arts live only in the old people's memories, some are still practiced. During 1981-82, a small grant from the Louisiana Division of the Arts helped the Clifton people revive some of their traditional arts, particularly basketry.

During the time when cotton was picked by hand, many people in the community made white oak baskets and sold them to plantation and gin owners on Bayou Rapides. These baskets, often as large as two or three bushels, could hold up to one hundred pounds of cotton. Back then, they were either sold for $.50 to $1.00 or else traded for corn and other goods.

The first of October was the best time to cut down the white oak, for then the sap was "on its way down." The oak with the straightest grain grew along the edge of swamp areas and was from 8 to 10 inches thick. After the sapling was cut down, it was split and then quartered. A butcher knife was used to keep splitting the pieces into thinner strips. According to an older basketmaker, the most important rule to remember during this stage, was to "watch the grain and split right on it." The strips were then put in a clamp and smoothed down with a drawknife or placed on a padded knee and worked with a pocketknife. The finished strips were about 3/8" wide.

The basketmaker had to get down on his knees to do the actual weaving. First of all, eight strips called "ribs" were laid across each other in a spoke pattern, and a strip the width of a thumb was woven around these twice. Then the basket was turned over, eight more ribs were added, and the weaving continued until the bottom was finished. At that point, the ribs were turned up and bound together, and the basket was left to set for one to two days before the sides were even. Either hickory or the sturdy heart of the white oak would be used for making the rim; the ribs were turned down on the inside, and two thick strips were fastened side by side around the top of the basket, one on the inside and one on the outside.

Basketmakers from the community who have either died or are no longer able to practice their craft are: Clayborne Clifton, Josephine Smith, Shirley Shackleford, Paul Allen Thomas Sr., Paul Thomas Jr., Agnes Tyler, Carroll Tyler, Louis Tyler, and Meriday Tyler. Though white oak with a good straight grain has become scarce in the Clifton area, the basketry tradition continues. Present-day white oak basketmakers who recently revived the tradition include: Clayborne's son, Luther Clifton, Louis' daughter, Pearl Tyler, Clayborne's great-granddaughter, Faye White, and Shirley Shackleford's great-niece, Monica Clifton. Due to the scarcity of straight-grained white oak, some community members have recently begun making baskets and vases out of pinestraw, an Indian and southern rural folk art. These basketmakers sew the dried needles from long-leaf pine trees into coils with either natural raffia or a manufactured nylon thread that comes in various colors. Pinestraw basketmakers include: Kathlene Thomas, Stephanie Thomas, Pearl Tyler, and Faye White.

Tupelo gum trays were items made in the "back days." These trays went for $.75 to $2.00 and were used for biscuit making. To make a tray, a piece of wood from one of the tupelos that grew along Sieper Creek was cut out and then burned1 to form a depression. A small foot axe or turpentine chipper finished the job of digging out the bowl part of the tray. Heavy and then fine sandpaper was used to dress it smooth. The trays were usually 12 to 16 inches long and 3/4" deep and could withstand "all kinds of abuse." Three of Edmond Tyler's sons, Meriday, Carroll, and Louis, made these trays. They also made biscuit boards, rolling pins, and wooden spoons out of tupelo.

Community members once pounded rice and other grains with wooden mortars and pestles. A hollowed-out pine, cypress or black gum log was used for the mortar. The logs, four to five feet in length, were burned on one end to create a deep depression. Then a wooden pestle was attached at an angle to a long pole. By pulling down on this pole and then releasing it, the pestle moved up and down, pounding the rice. Carroll Tyler remembers that his father, Edmond Tyler, had one of these mortars and that it made "good eating rice."

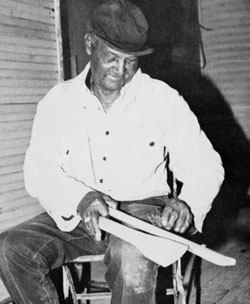

Axe handles are craft items still made in the community -- both the single and double-bitted types. These handles are made from hickory and fashioned with a hatchet and drawknife. Broken bottle glass is used for smoothing down the surface. Unlike many factory-made axe handles which are made from pecan, the home-made ones last a long time because they are made according to the grain of the wood. In the old days they sold for as little as 250. Luther Clifton and Myles Shackleford still carry on the ax handle tradition. These men also know how to make hatchet and hammer handles out of hickory.

People once made much of their own furniture: they built wooden rung chairs, safes, cabinets and presses. Some folks even built chairs and tables out of rattan vines. These vines, like the white oak, were cut in the fall when the sap went down. To make a table, the three legs were made first, and then a wooden box, the desired length and width, was used as a temporary frame for the top part of the table. The vines were held together with small nails and later painted. Although there is still a plentiful supply of rattan in the Clifton woods, vine furniture-making has become a lost art. People who used to do it were: Paul Allen Thomas Sr., Paul Thomas Jr., Carroll Tyler and John Tyler, Sr.

At one time Clifton people knew how to make their own houses. Instead of using nails, they fit pine logs together with wooden pegs. The Tom Neal house, now in the possession of Louisiana State University's Rural Life Farm Museum in Baton Rouge, was built according to the Clifton tradition. The house, constructed in the dog-trot or double-pen style, dates back to the 1860s. The only traditional buildings which still exist in the community are a few smokehouses and barns. Shingles were made from cypress or cedar and chimneys from clay. The inside walls of the houses were plastered with mud and then painted. One older man in the community recalls that in the winter these homes were comfortable and warm.

Other items made from wood include pine box caskets, rakes with hickory peg teeth, martin houses with shingled roofs, and ice skates made out of shingles or cypress wood.

Before the arrival of air guns and .22s, cane or elm blow-guns were used for hunting rabbits, blackbirds robins, redbirds, snowbirds, and quail. Older men remember that as boys they would go out at night carrying their blow-guns and firepans attached to long wooden handles. They would burn pine knots in these pans and rest the handles on their shoulders. On Sunday afternoons, families would go to their neighbors for dinner and afterward, the boys would shoot their blow-guns, seeing who could shoot the farthest.

The cane blow-guns were made from pieces of switch cane, 4 - 5 feet long and about 3/4" wide. Some of this cane would have as many as ten to twelve joints. A long hickory or metal rod was used to break through these joints. Once the joints were broken, a piece of tin that had been punched by No. 6 nails was fastened on the end of the rod and used as a scraper to smooth them. If a cane has crooked places, it was pulled through fire and pressed straight by lacing it on a long board between two straight rows of nails. The darts consisted of turkey or redbird feathers, pieces of pine whittled "smooth as a needle," or haywire. One end of the pine or haywire darts was usually wrapped 4-5" with tightly twisted cotton or thread. A well-made blow-gun could shoot as far as one hundred feet, depending upon the blower's "breath." Luther Clifton, Shackleford, Paul Thomas Jr., Carroll, Cleveland, and Leo Tyler still know how to make blow-guns.

Deer hide tanning is another Clifton tradition. Paul Allen Thomas Sr., taught the process to his sons, Paul Jr. and Joe. Paul Jr. tanned occasionally, but Joe did it as part of his livelihood. First the hide was soaked in water for several days. Then it was "grained" or dehaired by draping the hide on a log and scraping off the hair with a "beamer," a knife blade hammered into a piece of wood. Once all the hair was removed, the hide was "brained" by soaking it several days in deer brains or eggs. Next, the hide was stretched on a wooden frame and paddled until soft and limber. The last step was smoking the hide. Smoking turned the hide from a white color to a light or dark brown, depending upon the length of time the hide was smoked.

Cowhides were used for bottoming chairs. The hide was soaked for a day or two in order for it to stretch, and then it was cut to the right size along with the strings for lacing. After being laced to the bottom of the chair, the hide would dry and shrink tight. Though Luther Clifton still bottoms chairs, at one time "most everyone up and down the community did it."

Another item made from cowhide was a "blower," or bellows. A piece of hide was fastened over a wooden frame and sealed tight. At the front was a small pipe and at the back was an air hole and two handles that were used to pump in air. By providing a draft for the fire, the blower made coals so hot that they could actually melt iron. Plow points were sharpened by this method.

At one time Clifton people also made their own four or eight-plait whips out of rawhide or beargrass.2 Oftentimes the end of the rawhide whips were plaited with deerhide since it was more flexible. The handles, usually made from hickory, were as long as six feet and the entire whip itself might extend twenty feet. These whips had to be long since they were used for driving up to five yokes of oxen at a time. Sometimes smaller whips were made out of the white inner bark of the mulberry tree.

Until only a few decades ago, residents drank their well water from gourd dippers. A large round hole was cut in the side of the dried gourd. Then the gourd was either boiled or soaked in water for nine to ten days to get the bitterness out. These dippers were so sturdy that they were sometimes used to dip hot grease. Eventually, tin cups with handles took the place of these gourd dippers.

Gourds had other uses, too. They were, and to a limited extent still are, used for birdhouses. A small round or square hole3 is cut in the middle of each one, and then a wire is strung through two holes which are bored in the handle. Hung in a tree or from the porch roof, these houses attract martins. Dish Rag Gourds (loofa) were used for scrubbing pots and pans. The pod was first ripped down the seam and the "rag" taken out. Then, using a pocketknife, the rag was cut lengthwise and flattened out. According to Paul Thomas Jr., these dish rags were more durable than the modern "store-bought" kind and lasted for years.

Clifton people also made several different kinds of pipes. The simplest to make was the corncob pipe. Two holes were bored into the cob--one for the home grown tobacco and a smaller one for the cane stem. Pipes were also made from the briar root. First, a large root was dug up and dried. Next, using an auger, an inside bowl was bored out and dressed, and a hole was made for the stem. Some who made this type of pipe were: Myles and Shirley Shackleford, and Carroll and Leo Tyler. Paul Thomas, Jr. made clay pipes with cane stems, and though no one living still knows how to make them, "a long way back" the old people in the community smoked stone pipes with cane stems. These are sometimes referred to as "pure Indian" pipes.

The Clifton craft tradition also includes several kinds of whistles. One kind was made from the slit wing feather of a goose, another from pine bark, and a third kind from a short piece of cane cut at the joint and partially closed with a wooden stopper. Blowing horns, used for calling hogs and other livestock, were made from cow horns.

Until about 45-50 years ago, women in the community still made their own fans from the tail feathers of wild turkeys. Making the fan from the tail feathers was the easier of the two methods since the butt of the tailbone served to hold the feathers in place. First the women would trim the fat and oil from the bone, and then lace the feathers together (for 3-4") with strips of heavy khaki or mattress ticking and No. 8 thread. On the other hand, a wing fan required from 20 to 25 loose feathers, each one placed so as to "ride" halfway over the next feather. A smoothing iron was used to hold down the feathers during the lacing stage.

Other miscellaneous craft items were: palmetto fans, rugs "knit" out of grass, dogwood rakes, mattresses, floor mops, sage grass brooms, and scrub brooms. The scrub brooms were made from a wide piece of board with holes bored on two sides. These holes were filled tight with corn shucks that had been stripped thin and wet with water. Floor mops were made in a similar manner. Hay, corn shucks, or cotton served as the stuffing for mattresses that were simply cloth sewed up on all sides.

Quilting was a popular tradition performed primarily by the women. Often they came together for "quiltings" at someone's home. These were all-day affairs at which coffee and lunch were served. Some of the tops were pieced in block or crazy-quilt patterns while others were designed with log cabin, diamond, star or double-bitted axe shapes. The quilts were filled with cotton that was bought at the gin and then carded. When it came to the actual quilting, a fan pattern was the most common style. The quilting frame consisted of four rails that hung from the ceiling and could be raised to conserve space. Some community women who are still known for their quilting are: Alma Clifton, Lena Shackleford, Vada Smith, Violet Thomas, and Corrine Tyler.

Women also made their family's clothing. Store-bought patterns were, of course, at one time unheard of, and clothes were made from the "imagination." Women often made clothing out of a heavy material called "loyl." Though it came white, this material could be dyed different colors by boiling it with bark from the red oak or the less commonly used cherry bark or green walnuts. The women even made their own hickory needles and, after having picked the seeds out of the cotton, they spun their own thread. Besides sewing, women also knitted gloves and carded and spun their own wool. Men were also involved in the weaving process. James Tyler, Sr. is said to have owned a large loom which he knew how to operate.

Another tradition and one which is still carried on, though to a much more limited extent than in the past, is the making of cane syrup which takes place in the late fall, generally in November. Years ago, a horse or mule was harnessed to the mill, but today a tractor motor turns the cogs. As the cane stalks are fed into the mill, the juice that comes out runs directly to the wood-stoked vat where "skimmers" dip out the dirt which the heat has caused to rise. A "cooker" standing at the end of the vat has a variety of responsibilities. He must judge when the syrup has reached the proper consistency, instruct the other workers when to let more juice into the vat and how much, and then finally, he must also make sure that the fire is kept adequately stoked.

Years ago, community members made their sugar by this process, letting the syrup cook down until it solidified. Sometimes the syrup would be sold outside the community for 40-50 cents per gallon. At present, there are two mills and vats in the community, although only one set is in operating condition.

Children were also part of the folk arts tradition, making many of their own toys and playing Indian and folk games. They made "Tom-walkers" (stilts), "truck wagons" with actual axles and tongues, frog houses (castles in the sand), Easter eggs dyed green with leaves, clay marbles, dolls, and dogs. Popguns were made out of elm or cane. Children would break through the joints and then whittle a wooden ramrod that fitted inside the popgun. Chinaberries were the most popular ammunition, and more often than not, other children were the targets. If the marksman wanted the berries to stick to something, he stuck a straight pin through each berry. Rubber sling shots were also a popular toy. By using rocks, nails, or pieces of iron, children could shoot birds with them.

A favorite Indian game was called "chockala." Children would "chunk" balls at a red wooden rooster attached to a pole and the best out of ten won. When the bird was hit, the player would call out, Chockala! Children also played a knife throwing game called "Mama Peg" (possibly derived from Mumbley),4 tossed dollars, played marbles and a game called "bull in the pen," a predecessor to modern dodge ball. Older people remember, however, that when they were young there was not much time for games. Girls helped their mothers in the garden or house, while boys spent time hunting for hickory nuts and berries, toting firewood, cutting fence rails, and clearing the thickets which surrounded their homes.

As has been shown, the Clifton peoples' knowledge of homemade crafts, as well as that of the woods and farming, allowed them at one time to be almost entirely self-sufficient. Today, they can take pride in the resourceful nature and quality craftsmanship of their folk arts tradition.

Notes

1. Fires were started by striking two flint rocks together and "catching" the sparks on a piece of cotton. Oral tradition.

2. Beargrass, a type of yucca, was also used in smokehouses to hang pork. Oral tradition.

3. The Powhatan Indian Confederacy Tribes of Virginia were one of the few groups to put square holes on their birdhouses. Communication with Claude Medford.

4. Communication with Claude Medford.

Traditional Medicines

By Shari Miller and Miriam Rich

Older members of the community remember that in "back days," when it was too far to go to a doctor, people had to make their own medicines from what they could find in the woods.

Many of these remedies were herbal ones, snakeroot tea being, perhaps, the most important. Made from boiling the roots of the snakeroot, this infusion was good for colds and chest problems. It also provided an economic benefit. During the early 1900s, it was gathered, then sold to outside people for 35-40 cents a pound. A special hoe was developed for digging the snakeroot: it had an "eye" and was bent so that it did not damage the roots. Like many of the other useful herbs, snakeroot is not as plentiful as it once was. After the lumber companies cut down the virgin timber, undergrowth sprang up and choked out this plant.

The "ice vine" is still a popular medicinal plant among the older people in the community. Its leaves are placed on foreheads to bring down fevers or "mashed" and made into a poultice to "draw out" infections. In years past, this plant was cultivated near porches so that it could thrive on thrown out dishwater.

Sassafras tea was also a popular medicine. To a limited extent it is still used, but now mainly as a beverage and not for its medicinal properties. The roots of the white sassafras were boiled and the tea was then used for thinning the blood, relieving a sore throat, or bringing down a fever.1

Another useful herb was myrkle,2 an aromatic type of bay still plentiful in the Clifton area. An older resident remembers that it was good for almost anything- -especially a fever or upset stomach. The root was boiled and taken as a medicine, while the leaves could be put under the house to keep away fleas.

Bitterroot (or bitterweed), a small plant with yellow flowers, was another herb which was boiled to make a medicinal tea. It had a bitter taste -- like quinine -- and was good for fevers, particularly measles. When the cows ate these plants, the flavor could be detected in their milk. The leaves from the mullein could also be made into a curative brew. Other medicinal teas were: "shuck" tea (made from corn shucks), catnip, horehound, and sweet bay.

Sweet bay tea, widely enjoyed as a beverage, was commonly used for bringing down fevers. Though there aren't as many bay trees in the community as there once were, a few can still be found near springs of water. The fall of the year was the best time to gather the leaves; they would be picked in large bunches and then dried for two to three weeks. Often the branches, tied together by string, were hung from the kitchen ceiling to facilitate easy use.

Several individuals are remembered as being especially knowledgeable about herbal medicines. Besides being a faith-healer,3 Paul Allen Thomas Sr. also knew about herbs, as did King Brandy, who was sometimes even referred to as a medicine man. According to one older man in the community, people would go to the "King," asking about medicine. Another man remembered that when he was a child someone (though he could no longer recall who) would come to his home to cook medicine over the fire.

Community members also used non-herbal medicines. A mixture of sugar and rosin from a pine tree was beaten, then taken for a cough. Sugar and a drop of turpentine were sometimes used for the same purpose. When a baby suffered from "thrash" (sores in the mouth), 4 sow bugs were wrapped in cloth and placed in the infected mouth. Some prescriptions were of a preventive nature; a piece of lead worn around the neck kept one from getting poison ivy, and a buckeye carried in the pocket warded off rheumatism. An old practice used to prevent serious diseases from spreading relied upon individual sacrifice. A community member recalls Frank (Austin) Smith telling how his mother once said that when an Indian had an incurable sickness, he would be "sent out on the water" so as not to infect the rest of the tribe.

Though the old medicines are no longer in common use, the older people still vividly recall them and attest to their curative powers.

Notes

1. Sassafras was also used for another purpose. The leaves were dried and ground up to make gumbo filJ. Sometimes this was sold. For a good description of this process see: Bushnell, David I. The Choctaws of Bayou Lacombe, St. Tammany Parish, LA, Washington, D.C.: Govt. Printing Office, 1909.

2. Derived from the word "miracle. " Communication with H.F. Gregory.

3. "All he had to do was touch somebody, and they would be healed."

4. Another cure was to have a faith-healer rub the infant's mouth.

About the Publication and Authors

This publication originally appeared as Louisiana Folklife Journal, Volume VIII Number 1, March, 1983. Miriam Rich helped conduct the folk art survey. Photographs in the original publication were provided by Renee Hughes, Don Sepulvado, Greg Bowman, and Shelia Morrison.

Shari Miller and Miriam Rich are graduates of Goshen College, Goshen, Indiana. From 1980-82 they lived and worked in the Clifton community as volunteers supported by the Mennonite Church. Part of their work included documenting traditional crafts and planning basketry workshops. Ms. Miller received an MA in English at Northwestern State University in Natchitoches, Louisiana. Miriam Rich received an M.A.T. in French at the University of Chicago.

Claude Medford, Jr. learned about baskets for over thirty years, making and selling them for fourteen. His baskets are found in numerous private collections, in the Smithsonian, the Museum of the Southern Plains, Williamson Museum and Louisiana State University's Museum of Geo-Science. He is published in the Denver Art Museum Material Culture Notes, American Indian Tradition, and other periodicals. Claude served as a craft consultant to the Louisiana Folklife Program and the Natchitoches Folk Festival. He grew up in the northern edge of the Big Thicket (East Texas) and is a Choctaw descendant.

H.F. Gregory has been actively studying the archaeology and folk cultures of Louisiana for well over thirty years. At Louisiana State University, Dr. Gregory began his studies with Dr. Fred Kniffen, and he made many field trips with Dr. Harry Oster. Dr. Gregory's article, "Africa in the Delta" published in Louisiana Studies, remains an important examination of "Africanisms" in North Louisiana. He has published numerous articles on archaeology and folklore and has worked in almost every Indian community in the state. He received his Ph.D. from Southern Methodist University, completing a detailed investigation of the archaeology of Presidio Nuestra Senora del Pilar de los Adaes, a Spanish fort near Robeline, Louisiana.