Christmas Eve Bonfires & The Mayor

By William F. Fagan

Gramercy, in Saint James parish, Louisiana is a small, pleasant town on the Mississippi River about half way between Baton Rouge and New Orleans. It is home to some large industries such as Kaiser Aluminum and Colonial Sugars, and the smaller but widely known Zapp's Potato Chips. Gramercy has shipping and freight facilities on the river that make it a busy port as well. The town motto, "The Best Little Town for Miles Around," is followed closely by the claim that Gramercy is "The Bonfire Center of the River Parishes." A large sign welcomes visitors to Gramercy, reading: "The Bonfire Center, Spend Christmas Eve with Us." There is permanent steel and concrete bonfire structure at the same intersection, and the town's promotional brochure has a color picture of the Mississippi River levee with bonfire structures lining its top, stretching into the distance with the Veteran's Memorial Bridge in the background (see Figure 1).

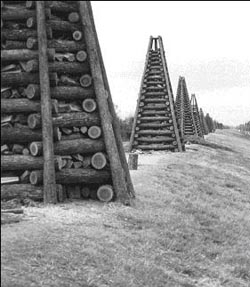

Gramercy's claims regarding being known for Christmas Eve bonfires are not unfounded. In her 1996 book Along the River Road, Mary Ann Sternberg explains: "Bonfires on the Levee is an unusual Christmas Eve celebration centered in the Gramercy-Lutcher area" (134). This is certainly true; in 1999 there were over one hundred bonfires built on the levee in Gramercy, Lutcher, and Paulina along the linear landscape of the levee-top just 3.4 miles long. Most of these temporary structures are concentrated downstream in Gramercy and Lutcher, with fewer in Paulina and a small number scattered along the other side of the river in Vacherie (see Figure 2).

Christmas Eve bonfires on the levee are not widely known outside of the Saint James parish area, however, for the past four years bonfires have been built upriver in Port Allen, which has its Bonfest the night before Christmas Eve (in order not to conflict with Gramercy). There are just three or four traditional teepee style pyres built beside the Mississippi, along with a replica of a ferryboat in 1997, a cabin in 1998, a wooden tractor and sugarcane wagon in 1999, and in 2000, a fifty-foot replica of the Baton Rouge/Port Allen-Mississippi River Bridge, complete with vehicles. The building of these bonfires is sponsored by the city and is not the efforts of individuals as they are downriver; it is very unlikely that the city authorities or Levee Board would allow this December 23rd celebration to grow to proportions larger than at present. Thus, Port Allen's Bonfest has fewer fires, but it is well attended; there are bands that provide live music, people fill the main street, and Bonfest has ended with fireworks as well.

Regarding the Gramercy area, Marcia Gaudet (1990: 199) said in a comprehensive discussion of this Christmas Eve practice: "The builders of the bonfires . . . do not feel that they are built for tourism" and continues (1990: 205) that ". . . the term festival is not applied by local people to the bonfire celebrations." However, more lately, as will be seen below, in the Gramercy region as well as in Port Allen, the building and lighting of the bonfires is no longer strictly a local, private, family affair, but has a component of tourist appeal, that during the late 1980s and early 1990s grew to huge proportions.

There is an organized bonfire festival held in Lutcher two weeks before Christmas. In 1999, there were numerous events over three days: live bands, a gumbo cook-off, a Christmas parade, and the Miss Festival of the Bonfires Pageant. The Festival of the Bonfires in Lutcher for the year 2000 expanded to four days and is the eleventh annual event. Each evening a sample bonfire is ignited, while work on the numerous pyres on the levee continues. The organizers of the spectacle in Lutcher-Gramercy know that the tourist appeal of their bonfires is valuable and has drawn many thousands of visitors to their area.

The lighting of bonfires built upon the Mississippi River levee on Christmas Eve night is a unique folk tradition embraced in a very small area of south Louisiana, and as other folkways, this tradition has undergone some changes and has evolved over time.

The Bonfires

If there was a specific practical purpose for these bonfires (other than celebratory), it seems to have been forgotten; however, there are a number of explanations one will hear regarding the origin of the practice of building and lighting them. One of the most popular today is that they are to "light the way for Papa Noel." The light from the fires assures that Santa will be able to find his way to the homes of the good girls and boys of Saint James parish.

Other explanations are based on somewhat more pragmatic purposes for these tall pyres. It is said that, many years ago, they were lit to help people cross the river after dark on their way to and from church and Midnight Mass on Christmas Eve. Similarly, another possible use was to guide boats on the river, helping them find their way home for Christmas, especially in fog. More likely, however, following a long history of bonfires on special occasions in Europe, Gaudet (1990: 195) explains:

Though this holiday custom is now practiced by people of Acadian French and German descent, it was probably not a custom practiced by the original Acadian and German settlers but reintroduced by the nineteenth century French immigrants. This could explain why the custom is not observed by the Cajuns on the bayous or the prairies of southwest Louisiana or, in general, by people on the first German Coast (Saint Charles parish). The custom was probably established in Saint James parish between 1880 and 1900. Father Louis Poche, a Jesuit priest and native of Saint James parish remembers hearing from his family that the bonfire custom in Louisiana was started in Saint James by the French Marist priests who came to Louisiana after the Civil War to teach at Jefferson College, then a Catholic college in Convent, Louisiana.

More directly, "The tradition was well established in Saint James and Saint John parishes before 1900, but definitely not before 1880" (Gaudet 1984: 11). Both Sternberg (1996: 134-5) and Lillian Bourgeois (1957: 154-5) agree that the tradition began with bonfires on New Year's Eve. The pyres were built on the batture (the strip of land between the levee and the river itself); only later, in the 1950s, were they lit on Christmas Eve on the levee. Writing about this practice, Marcia Gaudet recalls, "My own childhood memories of bonfires in Saint John the Baptist parish in the 1940s and 1950s are that they were very much an established Christmas tradition but much smaller and built in one or two days" (1990: 196).

Cane reed was and still is a popular material; it smokes heavily, pops and cracks loudly, and sends orange sparks into the air. Regarding earlier fires Bourgeois (1957: 154) explains: "The bonfire, built of cane reeds, was arranged in a cone shape with a heavy pole in the center to hold it up." For larger pyres, especially today, willow logs are used. The logs are fairly small in diameter, from four to about ten inches. They are plentiful along the batture, in ditches, and the nearby swamp. These trees grow very rapidly and have no commercial value, so they make a good supply of free bonfire material. Sternberg notes, "Willow is the wood of choice for building the bonfire structures that are the centerpiece of the Christmas Eve Festival, Bonfires on the Levee" (1996: 104).

The tall narrow pyramid or "teepee" shape pyres have, fairly recently, come to be considered the traditional form for the bonfire. Four, six, or eight sided, these teepees have long straight poles that make up the corners, lashed together at the top. Many shorter lengths are fitted between them horizontally for the walls, while the interior space is also filled in with small logs or scrap lumber and broken pallets that are usually hardwood, after being doused with kerosene or fuel oil to get them going. These tall pyres will burn for hours once they are lit.

The Mayor

It seems without doubt that the single most famous bonfire builder is also, presently and fittingly, the mayor of Gramercy. After attending Bonfest in Port Allen in 1998, I asked at that town office regarding who had built the teepees and Acadian style cabin that were burned for the festival. I discovered that the person responsible for their construction was Mr. Ronald St. Pierre, who kindly agreed to speak with me regarding his long-time involvement in this tradition. Mr. St. Pierre and I had long and pleasant conversations about Christmas Eve bonfires; Mayor St. Pierre explained how he got involved in this unique practice:

This goes back hundreds of years, you know, but I started when I was a little boy. I used to build myself bonfires in a cow pasture. It wasn't with willow trees, it was with old foxgrass, you just stack it, make it look like a bonfire. Then we got old enough when we can get hatchets and an ax to go and cut willow and burn it in a cow pasture. My father would never let me go on the levee because they were scared to death of the water and all. But after I got married ? I had an aunt who lived right here in the subdivision, I started building bonfires back of their house for the kids, and I just moved onto the levee and I got involved with the fire department and we built a couple of years for the fire department.

Gaudet (1990: 197) explains: "The traditional shape of the bonfires is that of a tepee though there have been some variations, such as the square pyre (or 'fort'), and beginning in 1975, small log cabins and ships." It was later however, in 1984, when the Mayor wanted to do something a little different, more spectacular, and for a number of years his bonfires captured tremendous attention and drew unprecedented crowds. Mr. St. Pierre explained, "The year I started with that little Cajun house [1984] I had 64,000 people

Then the year I built this river boat I had traffic tied up from Gramercy to Gonzales to LaPlace on I-10 and all the roads coming in." These spectacular structures, like the "Gramercy Goose," a willow replica of Howard Hughes' Spruce Goose (see Figure 3), and others listed below are built for the benefit of the town. Ronald St. Pierre claims that these bonfire festivals have put Gramercy and Saint James parish on the map. He noted, "I go with a non-traditional bonfire . . . we started and put it up and the news media got a hold of it and it went outrageous."

Traffic and crowds have tapered off on Christmas Eve the last few years however, as Mayor St. Pierre was unable to take part in the bonfire festival in Gramercy since 1993 due to an illness, and such grand fires as described below have not been undertaken by others. He is recovering; the bonfires in Port Allen in December 1998 were the first he has built since having undergone a number of surgeries. St. Pierre stated, "It will come back strong again because I'm going to be back involved with it this coming year so it's going to get better." His bonfire work in 1999 consisted of a castle on the levee and a detailed wooden tractor with a loaded sugar cane wagon behind it. Upriver, for his friends in Port Allen, he built teepee style bonfires and another cane wagon and tractor.

Regarding techniques and materials, the Mayor explained: "My daddy was a carpenter; we learned from him, I was the only one that stayed with it, fooled around with bonfires." He uses willow logs of varying diameter, as may be seen in Figures 3 and 4. For color contrast and tightly curved pieces, such as a circular stairway railing, he uses a vine found locally in swampy areas called blackjack vine. This vine is a very dark brown and is quite flexible when freshly cut, before it dries out. He noted, "It's all chainsaw work, a hatchet sometimes. I love it, and I wish I had a little training on different things, with the carving and all."

Mr. St. Pierre makes light of the amount of work that his non-traditional bonfire structures require. He gets help from his son, and some friends who have helped him for a number of years, but insists that the work goes quickly, including the gathering of the logs, which they do using ATVs. They then haul the logs to the site with a pickup truck and trailer. "The biggest work is the first two days, after that it goes pretty good," he noted.

Mr. St. Pierre keeps a guest book for people to sign, explaining that among the visitors to his bonfire structures he has had representatives from forty-six states and twenty-six countries. He said, "It makes me feel good when I'm lighting it and I see everybody there and you know, they start cheering and everything." With obvious pleasure, he explained the way in which people keep track of the progress of his projects, driving by day after day while he and his friends work, enjoying the construction as well as the burning of them later.

While the origins of the bonfires in Saint James Parish may have roots in Catholicism and Mr. St. Pierre is himself Catholic, when I asked him if he thought that the practice was, today, largely undertaken by Catholics, he responded that "Everyone does it, anybody that wants to."

Some of the Mayor's Bonfires

Beginning in 1984 with his "Cajun House," a bonfire styled after a traditional Acadian cabin, Mr. St. Pierre has completed a number of other non-traditional bonfires. They include:

- 1985 "Everwillow Plantation," a three-story plantation house, with a double curved stairway to the entrance. This large structure was built with strength and safety in mind. Mr. St. Pierre builds all of these structures so that people can go inside before he burns them on Christmas Eve. He builds the stairways in the same manner as those in a real house or other building. Flooring and supports are heavy enough to hold the many people who do go inside. "Everwillow" had a fireplace lined with mud so that a small fire could be lit, with the smoke going up and out the chimney. The Mayor is glad that people can enjoy these structures before they are burned, and is proud that there have never been any safety problems. He has never lost any logs into the river (these would be a hazard to navigation) and he carefully engineers his bonfires to collapse in upon themselves as they burn, without falling over or leaving large unburned pieces.

- 1986 "Gramercy Queen," a replica of a Mississippi River sternwheeler. At ninety feet long, this large structure had three decks that were accessible by well-built stairways. The paddle wheel on the stern was driven by an electric motor (removed before burning) so it looked more like an operating ship. Electric lights were also added, and as with the plantation house before and all his bonfires after, Mr. St. Pierre enjoyed adding as much detail to his projects as possible. Railings, seats, navigation lights, crowned exhaust stacks, windows, trim, and many other details were in evidence.

- 1987 "Gramercy Rig #1," a willow and blackjack vine version of a Gulf of Mexico oil-drilling platform, was an impressive sight. The platform held sheds, a crane, and a drilling tower. There was a helicopter pad with a helicopter perched upon it. The helicopter rotor blades turned, and inside the bubble canopy, made with blackjack vines, were controls and seats. He built a supply boat that was tied up to the platform and again, provided many small details to add to its realism.

- 1988 The largest project for Christmas Eve 1988 was the "Gramercy Express" (see Figure 4). It was a replica of a steam locomotive, with a tender, a passenger car, and a caboose. The Mayor explained that it was 105 feet in length. He incorporated steps and railings so people could walk through, and again, details such as controls in the engine, lights, seats, flanged wheels astride wooden rails and ties, and a perfect wooden bell made with a chainsaw were provided, as well as carved wooden chains between the cars. He also built a wooden automobile, a willow and vine Packard, with lights, seats, and smoky exhaust. He made the wheels from slices of a large diameter log, and the life-size car could hold passengers and be rolled along the ground. A third project for that year was a huge New Orleans Saints football helmet, with a curved face guard, again, made from the dark vine. While his wooden train is not the most massive bonfire he has built, the Mayor still considers it his favorite, and probably his best work.

- 1989 "Gramercy Goose" (see Figure 3), had seats for passengers, a cockpit with instruments fashioned from willow and vine, and controls and seats for a pilot and co-pilot. The Mayor covered the wings with burlap cloth and again added numerous details. The inside sections of the wings were weighted so that they would fold up and collapse inward as the fire progressed.

- 1993 Ronald St. Pierre's largest project was in 1993, his replica of the Louisiana State Capitol building. This structure was ninety feet wide, twenty feet deep and fifty-two feet tall, and was controversial, not because of the subject upon which it was modeled, but because of its tremendous size. Some people feared that the tower section might fall over while it was aflame causing injuries or a fire that might get out of control. Even without considering the height of the tower, it was a huge fire, but due to careful planning and experience, its burning went well and was enjoyed by thousands of people.

- The Mayor had provided steps up the levee that were inscribed with the names of the states and the year in which they entered the Union, like the real capital steps in Baton Rouge. There were three floors, mainly to hold more flammable material such as pallets and cane reed. Before burning, the building held many visitors who could enjoy it and read information the Mayor had posted inside regarding the Gramercy area, the State of Louisiana and Louisiana politics.

Not everyone thinks the Mayor's large, themed bonfires are a good thing. Among the newspaper articles he has that regard his work are a few in which complaints are voiced about traffic and other problems. Obviously referring to the work of Mayor St. Pierre and others who have built large non-traditional bonfires, Gaudet (1990: 197) explains:

Until the past few years, lighting bonfires on the levee on Christmas Eve was a true folk tradition in the area. Like many folk customs that come to the attention of the media and tourists, however, the bonfires seem to have changed considerably, becoming a spectacle with questionable tradition and shades of pyromania, along with ordinances to regulate them, complaints from ecologists, and commercialism. In the last five years, there have been definite changes in the bonfires, with major media coverage from the television stations in Baton Rouge and New Orleans and reporters from as far away as Atlanta. They have become a spectacular pyrotechnic display, drawing over 40,000 visitors in the last few years.

The Gramercy town offices have numerous pictures of these and other bonfires Mr. St. Pierre has built, and he has collected many newspaper and magazine articles that he was glad to share, as well as his time. Mayor Lynn Robertson of Port Allen also took time to talk with me about the bonfires in her city that were built by Ronald St. Pierre during recent years, and the way in which a tradition can evolve and be shared with others. She would like to see the practice of building these bonfires become a tradition in her town, and is pleased that it already serves to "draw people to our waterfront and downtown area." Mayor Robertson also explained that she considers Mr. St. Pierre's efforts on behalf of his town to be a wonderful thing, and although he may be somewhat under-appreciated, "He's quite an artist."

While defining folk art is a difficult endeavor not to be undertaken here, Mayor St. Pierre's constructions, although temporary, are the result of an evolving, long-term tradition and social occasion, and thus may be considered folk art. He is artistic, along with so many other people. I have been amazed at the time, effort, skill, and creativity that he puts into these projects, especially in the many small details that he so cleverly adds.

Looking at a photograph of his "Gramercy Express" I was compelled to ask, "All this, Mr. Mayor, just to burn?" He replied with a smile, "Just to burn."

Sources

Bourgeois, Lillian. 1957. Cabanocey; The History, Customs, and Folklore of Saint James Parish. New Orleans, LA: Pelican Publishing.

Gaudet, Marcia. 1984. Tales from the Levee: The Folklore of Saint John the Baptist Parish. Lafayette, LA: Center for Louisiana Studies.

_____. 1990. Christmas Bonfires in South Louisiana: Tradition and Innovation. Southern Folklore 47 (3): 195-206.

Robertson, Lynn. 1999. Interview by the author.

St. Pierre, Ronald. 19 February, 24 September 1999 and 27 October 2000. Interviews by the author.

Sternberg, Mary Ann. 1996. Along the River Road: Past and Present on Louisiana's Historic Byway. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press.