A Man Can Stand, Yeah: Ranching Traditions in Louisiana

By Jane Vidrine

I've rambled up and I've rambled down,

I've rambled this country all around.

I've been in the city and I've been in town

And I've got this much to say . . .

Before you take the cowboy's life

Get heavy insurance on your life.

Then cut your throat with a butcher knife.

It's easier that way.

On the surface, this closing stanza from "The Tenderfoot," an old cowboy ballad, is a warning to young men to think at least twice before getting involved with cattle. Yet it is also an expression of pride that a seasoned cowboy can overcome natural odds and his own shortcomings. As George Broussard of Cow Island says, "A man can stand, yeah."

Pride in knowing one's craft and being able to read his cattle and the land is a recurring theme in the stories of several generations of cattlemen recorded in Vermilion, Cameron, and St. Landry parishes.

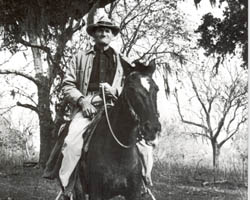

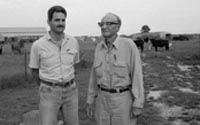

"I was born and raised on a horse," begins eighty-plus year old George Broussard, a Vermilion Parish cattle rancher who still works his herd daily with his son, Glynn. George Broussard's family has been in the cattle business since his grandfather Ernest Broussard came to Cow Island from New Iberia in the 1870s to work cattle for Demonstane Nunez. Eventually Ernest Broussard bought out Nunez and expanded the operation until his death in 1905, when son Joseph E. Broussard became the ranching patriarch. Three generations hence have continued the Broussard ranching tradition.

George's first cattle drive to the coast was in the early 1920s. As he recalls,

Papa [Joseph E. Broussard] would drive the cattle. It would take a week to drive them over there--through Little Prairie, White Lake, Pecan Island, Stump, Belle Isle, Chênière au Tigre, Mulberry, Belle Ridge . . . . We would drive 'em at night by the light of a good moon, when the water was high . . . . Of course, in these times there was no gravel. There was just dirt road here. Oh yeah, when my grandpa [Ernest Broussard] lived there, there was no road at all. It was open prairie--jus t a trail to go to town [Abbeville]."

There were certainly no roads through the marsh to the coast, only trails whose routes were well traveled by cattlemen, trappers and farmers on horseback and by boat. Every Fall the cattle were (and in some cases still are) driven to the coastal marshes where the grass was nutritious, plentiful, and green throughout the winter. In the Spring before the mosquitoes got too thick they were rounded up, branded and brought back to the prairie pastures for summer grazing or to be sold.

Amanda Sagrera Hanks in her book, Louisiana Paradise honoring her cattle ranching ancestors of the chenieres, remembers Raphael Semmes Sagrera of Chênière au Tigre.

He acted as trail boss for herds of cattle his father had started building in 1887, moving cattle from Chênière au Tigre's access marshes to Little Prairie and then on the Russell Green weighing station at Cow Island. From there, the drive continued to Kaplan, where the cattle were loaded in rail cars and shipped to Oklahoma City, New Orleans, or Morgan City. After a seven day ride, usually 800 or 900 cattle arrived to be sold for as little as four cents a pound."

The most common memory of these cattle drives is crossing canals with herds of 400 to 600 cattle and different tricks used to get cattle to cross. "I remember Papa," said George Broussard. "[If] they didn't want to go, he'd shoot his pistol in the ground. It'd scare 'em. They'd jump in." Sometimes, if a canal or bayou was shallow enough, the riders would cut the tall, dense marsh grass with a sickle they carried on their saddle and make a thick grass mat for the cattle to walk on. Other times they wo uld swim the cattle across by dismounting and guiding a horse in the lead. Most of the time there was a lead steer who had made the route many times and knew what to do. All the men had to do was talk to them. They would cross and the rest of the herd would follow. But that didn't always work as planned and the men spent a large part of the drive with wet clothes and gear.

Earl Couvillion, Broussard's nephew by marriage, told of one such drive in the 1940s.

One day we got to the ferry in Forked Island--it's just a small ferry-- with about 60 to 70 head of cattle. We got on the ferry and we had a Brahma bull on there and he decided he didn't want to stay on there so he came off! And when he came off, the whole herd came off. I can remember Grandpa Joe, he nearly stopped them . . . but he didn't stop them. Well, this was about 9 or 10 o'clock in the morning . . . . It was about 4 o'clock in the afternoon we finally crossed them nearly all . . . . But after that we never drove them on the road again. We had the flatbed trucks.

These calamities are taken in stride as all in a day's work. Hurricanes the magnitude of Audrey in 1957, harsh winters such as that of 1927 and floods as in August 1940 when it rained 46 inches in three days and the tick fever of the early 1930s were devastating to herds and offered a challenge to even the most tough skinned cowman. Yet the cattle industry has persisted in South Louisiana.

One wonders how Louisiana has been able to compete with Texas and other range cattle states. Several cattlemen interviewed answered simply. "The only thing I can tell you, Louisiana has such fertile soil. In Texas it takes 10 acres for one cow. But in Louisiana, if you take care of your soil, you can raise one cow per acre" (Earl Couvillion). There even seems to be a sort of attraction for some in working in such a varied and unconventional cattle raising terrain. As Brownie Ford, noted cowboy singer and ex-show and working cowboy, told folklorist Nick Spitzer about being a Louisiana woods cowboy, "A woods cowboy is a man that can go in these thickets here. I worked in Texas where they got a lot of brush country there too and I never did work on the open plains much, seemed to me there wasn't any challenge there. In the brush, only the fit survive!" Most marsh and prairie cattlemen would agree.

Louisiana's Early Cattle Industry

If I had hair on my chin I could pass for a goat;

That bore all the sins of the ages remote.

But why it is so I cannot understand;

For each of the patriarchs owned a big brand.

Abraham emigrated in search of a range;

In looking for water was seeking a change.

Now Isaac run cattle in charge in Esau;

and Jacob punched cows for his father-in-law. /p>

The cattle industry in Louisiana does not date back quite as far as the cowpunchers in this old song called "The Cowboy," but has its roots in Louisiana's colonial period. Before the entry of Texas to the Union in the mid-1800s, probably the largest cattle raisers in the United States were in Southwest Louisiana.

William Darby described cattle raising in Louisiana in the early 19th century: "The prairie Mamou is devoted by the present inhabitants to the rearing of cattle, some of the largest herds in Opelousas are within its precincts. Three rich stockholders have, as if by consent, settled their vacheries in three distinct prairies. Mr. Wikoff, in the Calcasieu prairie, west of the Nezpique, Mr. Fontenot in prairie Mamou; and Mr. Andrus in Opelousas prairie. Those three gentlemen must have collectively fifteen or twenty thousand head of near cattle, with several hundred horses an d mules. It may be presumed that Mr. Wikoff is at this time the greatest pastoral farmer in the United States." (Darby 1816).

Cattle were brought to the New World by the Spanish soon after 1492. As Lauren C. Post explained in his collection of essays, Cajun Sketches, "The vacherie of the old Acadians who came to St. Martinville and Opelousas in 1765 was the dominant feature of their early cattle industry. It was to them what a rancho or a hacienda was to Spanish-speaking people of Texas and Mexico." The cattle were longhorns which were hearty and about half-wild, easily adaptable to the changing climate and native grasses of Louisiana.

"Our cattle in Attakapas differ from those in France very materially by their extraordinary fine horns, which are generally about two and a half feet long, so that with these and their long shanks and feet, when seen from a distance, they look more like deer than like cows and oxen--their usual red-brown color heightens the illusion." (Sealsfield 1799).

During the second half of the 1700s, New Orleans misfortune became the Acadians' advantage. New Orleans was experiencing a grave shortage of meat at about the same time as the early Acadians arrival in Louisiana. The Acadians were independent, desirous of settlement where they could re-establish a lifestyle close to that which they had in their homeland. They agreed to raise cattle on shares for Bernard Dauterive in the Attakapas district west of the Atchafalaya.

The Acadians were energetic in their ranching pursuits, as was observed just a few years later, in 1770.

"The cattle are admirable in appearance, weight and quality of meat. They usually weigh up to 800 livres. The raising of cattle is the natives' sole occupation . . . . The natives sell the cattle to the city dwellers and to the colony, but they do not derive as much profit as they could from the cowhides even though they have everything they need to establish tanneries." (Martin 1770).

By 1802, the Louisiana cattle industry was firmly established and the prairies were the main suppliers of beef to New Orleans and points northeast. Many economic hardships, not the least of which were the aftermath of the Civil War, storms, floods, epidemics such as the tick fever in the 1930s and federal regulations imposed during the 1970s on the price of beef, have periodically challenged the industry. Yet ranching has persisted in Louisiana. Improved breeds and intelligent land management have maintained Louisiana as a competitor on the national market.

Ranching and Technology: Conflict or Continuity

Before the tick fever of the 1930s and the widespread practice of dipping and vaccinating, little was attempted in the way of doctoring herds in Louisiana. Nor was the diet of native grass supplemented with feed or cultivated pasture. Ranchers were indeed concerned about the welfare of their cows and about getting as much as they could for them at market, but simply, the resources were not available. Today, raising cattle, is a complicated business which relies heavily on medical, economic and agricultural technology.

Folklorists tend to view technology as a threat to traditional lifestyles, but this is only partly true in this case. Many of the earliest cattle families have persisted in the business and use the available technology as they see it is applicable to their operation. Yet, when it comes to the cows, a cattleman still needs to know just what the old-timers did--how to read his cows and the land.

One cannot look at the cattle industry as an effort only related to the breeding and selling of cattle. Always ranching has been integrated with other agricultural pursuits, such as rice and soybean farming, trapping, hunting and fishing, each in its season, and oil exploration and production. As Brownie Ford so aptly put it, "The smart cowman is the one with oil derricks for his cows to scratch on." Many of the enduring Louisiana ranching operations, such as the Gray ranch near Vinton, are examples of such an endeavor.

Richard Clay Chapman, director of cattle operations for Sweet Lake Land and Oil Company manages a large commercial herd of Brahma hybrid cattle and oversees farming and oil production on the expansive ranch which extends roughly from just south of Iowa in Calcasieu Parish to Sweet Lake in Cameron Parish. Clay was "broke" on ranches in Colorado and Wyoming and returned to Louisiana to pursue his degree in animal science at Louisiana State University. Ranching is "in the family" since Clay's father Holl is is beef cattle specialist for the state at Louisiana State University.

Clay's banter, as he toured the ranch in his Jeep Cherokee, was a mix of business talk and nature guide.

"What we have here is a pump-off operation (water is drained from the land to allow for cultivation and pasture). We have Angus and Angus-cross. Some of these heifers are Brahma cross with a Simmbrah bull. These cross-breed cattle are more resistant to disease and insects, they have longer milking and more heat tolerance.

The ranch was started by a man named Harry Chalky, a Scotsman who came in the 1880s and bought land for one bit per acre. You know what two bits is--a quarter. Well, half that per acre. They say he owned just about from here to the Texas border at one time. But they sold parts of it during hard times. Those pine groves over there were planted by the Conservation Corps in the 1930s as a wind break. All those tallow trees took over after Audrey blew them in.

I've been here for a little over a year. There's a lot of work to do. Right now, we're at about ten acres to one cow and I'm planting and improving the land to have one acre to one cow in about five years. I'm planting 2600 acres in rye grass (a nourishing pasture grass) this fall. Frugé's Louisiana Flyers can plant all that in two days after we plow the land and apply herbicide to kill off the trash plants. We also graze the rice stubble to prevent red rice and for regrowth.

My crew is one herdsman and five cowboys just for cattle operation, cattle work, hay and feeding. I hire contract cowboys such as Chris Matheson during the busy times. He is so good, he can do anything having to do with cattle.

We vaccinate for everything here, every Spring and Fall. It's a question of economics. At fifty cents per pound for instance, if you lose a cow calving or because she is sick, you not only lose her but her future productivity. In the old days they bled the land. But with planning, technology and planned breeding seasons, we can do a lot better. Today, I can call Houston for vaccine and they send it to me UPS. We can load a trailer with twelve horses and drive to the back pasture, put the cattle i nto a chute, treat them, turn them out. It saves a lot of time. Now, I can even sell my calves over the satellite video network."

Clay is the personification of the epitaph in the song "Zebra Dunn,"

There's one thing and a sure thing

I've learned since I've been born

Every educated feller

ain't a plumb greenhorn!

Tools of the Trade

For the working cowboy on horseback, the saddle is not just a place to ride but also a sort of pick up truck, carrying all the necessary gear for working in the field. Some of the essentials were a bedroll, slicker, dry clothes, rope, sickle, brand, matches, hatchet, medicines, mosquito whip and of course, a branding iron.

Branding cattle has been practiced since the earliest times and serves as identification of cattle with a certain owner. Brand books, official registers filed with the state, record brands dating back to 1739. Brands are often handed down from one generation to the next and continue to be a source of family pride and tradition. Even though recently developed ear tags and ear marks are very efficient in helping a rancher keep a record of his herd, identifying which calves belong to which cows and what year they were born, young men such as Clay Chapman and Glynn Broussard are proud to have the brands of their ancestors.

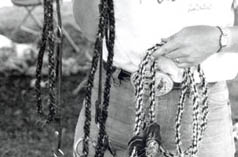

Essential to the cattle industry has been the saddlemaker, who provides custom equipment including bridles, whips, spurs, and saddles. Cotton Hebert, J.E. "Boo" Ledoux, Noah Comeaux, and Terry Cox are four South Louisiana saddle makers who furnish the cowboys in their own "neighborhoods." Cotton Hebert has his saddle shop on the 4-T Ranch, owned by Donnie Matheson in Cameron Parish. He has been repairing saddles for 35 years and fabricating his custom saddles for over 15 years. For many years he was also a resident ranch hand for the F-R Ranch in Gum Cove. His working saddles are finely crafted, fitted perfectly to the particular horse and rider, tooled and beautifully finished. One of his most popular models is what locals call the "Cameron saddle," a comfortable saddle with a wide seat and large swells. Cotton's whips are made with a spliced end called a "Louisiana tail" which is easily replaced once it wears out.

Terry Cox is a saddlemaker and fifth generation cowboy in the Sweet Lake community in Cameron Parish. His handmade buggy whips and bull whips made of hickory or bois d'arc, also known as "Osage orange" are widely used by local cowboys and cattlemen. At the end of his whips, Terry places a "popper" which his wife Valerie makes of twisted nylon fishing string and coats with beeswax. He considers two things when making a saddle: "comfort for your horse and comfort for your rider . . . blistering the horse's back or blistering the rider, then they won't perform right."

The story of old-time and modern-day cattle ranching in Louisiana is one which deserves a lot more investigation than is possible in this short essay. Cattlemen are a group of people who have been a major force in the shaping of Louisiana's cultural and agricultural landscape. Louisiana's cattlemen are not boastful. Rather they are matter-of-factly modest about their lives and achievements. According to Papa Broussard in an interview with his grandson Alan, "It takes a lotta acres, lotta know-how and a lotta determination."

La Valse du Vacher

Malheureuse, j'attrape mon cable et mes éperons

Pour m'en aller voir á mes bêtes,

Mon cheval et selle, c'est malheureaux de me voir

M'en aller moi tout seul, ma chérie.(Cowboy Waltz as sung by Denis McGee from The Tools of Cajun Music)

Sources

Ancelet, Barry and Elemore Morgan, Jr. 1984. Travailler, C'est Trop Dur: The Tools of Cajun Music. Lafayette: Lafayette Natural History Museum Associates.

Darby, William. 1816. A Geographical Description of the State of Louisiana. . . . New York: James Olmstead.

Martin, Paulette Guibert, trans. 1770. The Kelly-Nugent report on the inhabitants and livestock in the Attakapas, Natchitoches, Opelousas and Rapides Posts.

Sealsfield, Charles. 1799. Cabin Sketch Book of the Southwest.