Fait à la Main: About Louisiana Crafts

Edited by Maida Owens

From 1986 - 2008, the Louisiana Division of the Arts offered the Crafts Marketing Program which published, Fait à la Main: A Source of Louisiana Crafts in 1988, 1991, and, in 1995, it was published online. The publication was a directory of juried Louisiana craftspeople provided as a source book for shop owners, gallery oweners, interior designers, architects, and collectors of handmade crafts. The program included many different types of craftspeople, targeting various markets. The About Louisiana Crafts section is reproduced here as an overview of crafts in Louisiana.

Three Types of Craftsmen

Three types of craftsmen participated in the Louisiana Crafts Marketing Program. The distinction among them is based on the context in which the craftsmen learned their crafts and the relationship of the crafts to their communities. The particular medium or product is not usually a significant distinguishing factor.

Contemporary craftsmen have been self-taught or formally trained in classrooms or workshops. They make personal artistic statements with their crafts. Self-taught, contemporary craftsmen have been influenced by books and magazines from popular culture rather than by folk culture.

Folk craftsmen maintain traditional crafts learned within their own community. Their skills are passed down orally or by example rather than learned in the context of a classroom or workshop. Although some folk craftsmen may be self-taught and express a high degree of individuality in their work, the works of folk craftsmen reflect the culture and aesthetics of their folk group or communities.

Revivalist craftsmen produce traditional forms, but their training has come from outside the traditional community through books or workshops.

Folk Craftsmen

Folk craftsmen and their crafts are frequently misunderstood. Differing from revivalist and contemporary craftsmen, folk craftsmen learn their crafts within a traditional community where those crafts have significance and traditions of use and value. Learned informally in families and communities over generations, not through books or workshops, folk crafts suit local needs and follow the aesthetic standards of the community.

The term crafts refers both to processes (e.g. basketmaking) and products made through those processes (baskets). Crafts in the product sense are utilitarian items fashioned for use in the daily or annual round of work activities (baskets may be used for storing cotton), or for use in carrying on everyday life in an efficient and satisfactory manner (e.g. clothing and bed coverings). Although the craft items may have an aesthetic dimension, the utilitarian aspect is predominant. When the aesthetic element predominates, it is folk art. However, when the crafts product is used in a ritual context (such as grave wreaths) or to create some art form (e.g. traditional musical instruments), the dividing line between folk crafts and folk art is a fine one (Spitzer 1985:133).

As a result, folklorists, anthropologists, and some museums frequently use the terms folk crafts and folk art interchangeably. The definitions of folk art, traditional crafts, and naive art differ from those used by many in the world of fine art. The fine arts' definitions reflect a different perspective and emphasis -- a fine arts aesthetic. Many in the art world consider folk art to be the work of untrained, naive artists such as Louisiana's Clementine Hunter. While some naive painters may use community images in their work, their paintings are individualistic and document the individual's own version of traditional life. Often this represents the community's nostalgic view of the past. The important distinction is that painting is not a traditional skill passed along. Therefore, the work is not folk art or traditional, but naive art.

Folk craftsmen originally created objects for use and appreciation within their own community. When these objects are taken out of context and become collector's items or tourists' souvenirs, both the product and the process which created it are impacted. Folklorists and anthropologists are concerned that the effect on folk crafts may be detrimental to the tradition. Emphasis on selling to the highest paying buyer can stimulate cultural intrusion such as modification of traditional forms to increase marketability.

Some crafts are threatened with extinction. Modernization and inexpensive imports have displaced many traditional crafts. Cornshuck mats, horsehair ropes, quilts, wagon wheels, and split oak baskets are no longer required in everyday life. Other traditional crafts such as Chitimacha or Choctaw Indian double-weave spilt-cane baskets are endangered because of the extensive amount of time required to produce them. Frequently, young people are hesitant to learn traditional crafts that demand so much yet do not reward them monetarily. As a result, some folk crafts grow increasingly rare. When that is the case, marketing programs, such as the Louisiana Crafts Marketing Program, can assist by providing resources to craftsmen so that they can market their crafts more effectively, continue to live in their traditional community, and increase their standard of living. Since traditionally most folk crafts were not made for sale, but rather for personal use, enjoyment or giving, only a small percentage of Louisiana' folk craftsmen are included in this program.

For citations, refer to the Louisiana Folklife Bibliography.

Louisiana, with its mingling of Catholicism, African religions, Protestant traditions, and Native American sacred practices, is known for numerous ritual and celebratory activities. Many folk crafts in these ritual and festival occasions are made for a family's own use and have not traditionally been made for sale. Examples include fig breads made for St. Joseph's Day altars by Sicilians throughout the state, the painted ceremonial coconuts given out at the black Zulu Mardi Gras parades, or Choctaw Indian ceremonial rattles.

Other folk crafts are made for purchase within the craftsmen's own communities, but the craftsmen have yet not chosen to offer these to a wide market through the Louisiana Crafts Marketing Program. Examples are decorated umbrellas used in jazz parades, authentic voodoo dolls of reed and cloth, or the ribbon baskets and sashes of the New Orleans social clubs. Mardi Gras, which occurs forty days before Easter is the best known ritual event in Louisiana, but most people do not know that it is celebrated in different ways throughout south Louisiana. The rural Cajun Mardi Gras involves clowns on horseback begging for chickens for use in a communal gumbo. In the New Orleans black neighborhoods, groups parade in elaborate feather Indian costumes. Folk craftsmen from these two traditions offer authentic costumes for sale here. For more information, the virtual exhibit, “The Creole State” An Exhibition of Louisiana Folklife has a section on Ritual and Festive Traditions.

Native American Crafts

Louisiana has several groups of Native Americans who maintain their traditional crafts. In addition, some are isolated from their tribes, but continue their craft traditions. Some Native American crafts are shared by several tribes, and others are unique to one.

The French-speaking Houma Indians numbering about 5,000 are the largest Louisiana tribe of Indians. Living along Bayou Lafourche in the marshes of south Louisiana, they use a wide variety of natural materials in their crafts. Palmetto, a native, wetland palm, is woven into hats, fans, hats, and decorative coverings for blowguns. Traditional Indian baby dolls are formed from dried and cured Spanish moss. Miniature cypress pirogues, miniature duck decoys, and crawfish and crab effigies are carved from cypress or tupelo gum.

The Chitimacha of Jeanerette are few in number, but they have a strong tradition of basketmaking using rivercane which grows along the edges of Louisiana's bayous. Faithfully reproducing red, black, and yellow traditional patterns such as "Alligator Entrails," "Rattlesnake," and "Muscadine Rind," the Chitimacha make a variety of baskets and trays. The double weave basket, which is a basket with two layers, or a basket within a basket, is more difficult to make than the single-weave basket and can be woven tightly enough to hold water.

Four bands of Choctaw live in Louisiana: the Jena Choctaw, the Clifton Choctaw, the Apache-Choctaw of Ebarb and the Bayou Lacombe Choctaw. Both woven rivercane baskets and coiled pinestraw baskets are made by the Choctaw.

The Choctaw of Jena weave rivercane baskets, but also continue tribal traditions such as tanning deer hides and making chinaberry seed necklaces. A few also make the traditional ribbon shirt preferred by the Choctaw men.

The Clifton Choctaw still make white oak baskets which have traditionally been made both for supplemental income and home use. The pinestraw baskets reflect their bold sense of color and unorthodox shape. Quilts embody the same community values. Although quilting stitches often follow the fan pattern common in the U.S. South, traditional piecing patterns place strips of fabric in uniquely asymmetrical designs.

The Coushatta (or Koasati) Indians living near the town of Elton in the southwest prairies of Louisiana are well-known for their coiled baskets and trays using long-leaf pine needles. Sewn together with various traditional stitches using natural or dyed raffia, they are frequently decorated with flowers of raffia or small pinecones. Baskets of wire grass are made more rarely because of the scarcity of the grass. Since the 1960s, several basket makers make effigy baskets in the form of bears, crabs, frogs, and crawfish. Innovation within traditional boundaries is clearly, still an active force in folk crafts.

The Tunica-Biloxi Indians live near Marksville. A few still continue the traditional skills of coiled pinestraw baskets, doll making, and beadwork.

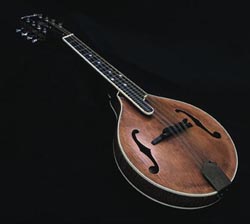

Folk Instruments

Musical instrument making in Louisiana came about primarily because of the unavailability of store-bought instruments. Many Louisiana communities remained isolated until World War II. But the settlers of Louisiana were farmers and not from traditional instrument making families. Rather than do without, they made their own instruments. The refinement of techniques and materials slowly evolved, and ingenuity solved problems.

For both the Cajuns and Creoles of south Louisiana and the British-Americans of the north, the primary instrument was the violin. Even though mail order houses made the violin readily available in the late 1800s, self-trained fiddle makers continued their craft. Spruce is not indigenous to the south, so its fine acoustic properties for violin tops were sometimes substituted with local fine-grained cypress. African black ebony was also unavailable for pegs, fingerboards, and chin rests; but the heart of wild persimmon (which is the same genus of ebony) had the same color and density and could be polished to a similar sheen. A tail piece could be carved from a cow horn, and a chinaberry branch had almost the same resilience needed for a bow as that of fine Brazilian pernambuco.

While violin making and playing was establishing itself, a new ethnic group arrived in south Louisiana about 1850 and brought a fairly recently invented instrument -- the German diatonic accordion. So great was this instrument's popularity that it immediately overshadowed the violin. This was due to this tremendous volume, its incorporation of a bass/chord accompaniment, and its ability to withstand humidity and heat compared to stringed instruments. Also, the fact that it lacked strings eliminated the need for frequent tuning.

Imported instruments satisfied demand until World War I halted all importation of German-made products. During this time, the popularity of the diatonic accordion declined -- even in Louisiana. By the time interest in the accordion was revived among the Cajuns in the late 1940s, the German made accordion has been modified to the point that it no longer looked, sounded, or played as Cajuns preferred. So Cajuns learned to repair and tune their old pre-war instruments through trial and error. Eventually, the old German accordions suffered from material fatigue because of frequent repair, and the Cajun began fabricating new ones using parts taken from contemporary ones. Today, the Cajun diatonic accordion, featuring exotic woods with mother of pearl inlays, is most frequently tuned in C or D to produce the distinctive sounds of Cajun music.

The Cajun triangle, know in Cajun French as t-fer (little iron) is a percussion instrument that provides a unique ring which Cajun musicians love. Fabricated from the high tensile steel salvaged from old horse-drawn hay rakes and the spring bars from the bundle carriage of rice cutting binders (reapers), the t-fer in the hands of a Cajun musicians is much more than a dinner bell. Recently, some craftsmen have begun to make the frottoir, or washboard, characteristic of Creole zydeco bands, by hand. Most bands, otherwise, have them custom made by local sheet metal companies.

For more information, the virtual exhibit, The Creole State: An Exhibition of Louisiana Folklife has a Folk Instruments section.

Domestic Crafts

Domestic crafts, also called household crafts are made for work and play around the home. Today, most domestic crafts are not created from need so much as from habit or a nostalgic desire to maintain rural subsistence traditions. Natural materials such as cornshucks, tupelo gum wood, sedge grass, cow hides, river cane, and gourds, found in abundance are used to create household furnishings, supplies, and amenities.

In Louisiana, cornshuck weaving has been primarily retained among African-Americans, but in the past it was widespread among all rural communities. Cornshucks continue to be twisted, painted, and woven into purses, door mats, hats and chair bottoms. Chair bottoms are also made from cowhide, deerhide, or split oak. Split oak is also the most common basket material used by the widest range of cultural groups in Louisiana. African-Americans, British-Americans, Cajuns, and Native Americans continue to harvest their own trees, hand split the oak, and weave traditional forms. Originally made for specific tasks such as picking cotton or gathering eggs, the same forms decorate their makers' homes and are collectors' items today.

Quilting is one of the strongest traditional crafts in Louisiana and quilters continue to work alone and in groups. Frequently quilting bees, where women traditionally gathered today, have moved to senior citizen centers. Louisiana has both the more familiar traditional British-American quilt patterns such as the "Lone Star" and "Double Wedding Ring" and the less familiar African-American strip quilts which use linear, bright, multi-colored strips, often asymmetrical in design. While traditional quilting is common, traditional weaving is quite rare. The handwoven napkins from brown cotton homegrown and handspun by Gladys Clark and Elaine Bourque represent the last of the Acadian weaving tradition.

Other traditional Louisiana domestic crafts available are traditional straight-back chairs, porch rockers, willow furniture, birdhouses, dough bowls carved from tupelo gum, and a wide range of folk toys such as puzzles and whirligigs. Many domestic crafts may be decorative as well as functional. Decorative folk crafts are those traditional items that emphasize the aesthetic dimension. However, many of the items in other categories such as the Mardi Gras costumes, accordions, quilts, and baskets also clearly have an artistic dimension. Likewise, a number of the decorative items here have function in addition to their pleasing or unusual style and appearance.

For example, walking sticks are still used for support as well as swagger. The African-American walking sticks of David Allen are decorated beyond what is necessary for the object to function. Allen's work is visionary: ideas for his cane designs "come to him" through dreams or just imagination. He looks at the root shape of the young sapling used to form the handle to "see" what animal or other shape is hidden there. Although he did not learn from another carver, whittling was a common pastime in his community, and walking sticks were often carried to ward off dogs and other trouble. Many of the motifs used in his canes incorporate common objects, animals, and beliefs from his traditional background.

For more information, the virtual exhibit, The Creole State: An Exhibition of Louisiana Folklife has a section on Decorative Crafts and Domestic Crafts.

Rural Occupational Crafts

Occupational crafts are those handmade items that are made for use within a community and relate to fishing, hunting, and farming. They are also the tools and products of trades such as blacksmithing, boatbuilding, stone masonry, and carpentry. Even though function is significant with occupational crafts, the object still reflects the group's aesthetics. An accomplished tool maker is seen as an artist among his peers. Except for blacksmithing, occupational crafts are frequently not made in quantity for sale. As a result, few occupational craftsmen have sought assistance from the Louisiana Crafts Marketing Program.

While fishing, hunting, and agriculture are pursued increasingly for pleasure rather than work, many traditional work-related objects retain their value whether the goal is subsistence, cash income, or sport. On the other hand, some items, especially tools, are being replaced by mass-produced goods. Thus traditional work-related crafts items are sometimes viewed out of context as antiques or art objects.

Horsehair rope making is another widespread craft in Louisiana that is still practiced by Cajun and Creole cowboys of southwest Louisiana. But few see the craft as a source of income and do not attempt to sell their ropes. The blacksmiths in the program exhibit a range of skills and interests. Many blacksmiths traditionally practice other crafts since communities may not be able to support a full time blacksmith. Like other blacksmiths before them, Karl Nettles and Jim Jenkins make wagon wheels and are two of the few wheelwrights in Louisiana.

Boatbuilding is alive and well in Louisiana although few outsiders are aware of it. Most traditional boatbuilding in Louisiana takes place in small villages along the bayous of south Louisiana. The tradition developed within a varied polyethnic cultural setting, largely deprived of formal educational opportunities which was historically cut off from many elements of "mainstream America." In consequence, this maritime heritage has been taken for granted at home and ignored by the outside world. Early French travelers moved along watercourses in pirogues fashioned from cypress tree trunks. At the turn of the twentieth century, the classic dugout pirogue was only 14 feet long and light enough to be carried by a single individual. As the availability of materials rapidly changed, the pirogue came to be built of cypress planks, marine plywood, fiberglass, and finally sheet aluminum. The basic form has altered little from the original Native American model.

Boats with a flat bottom and a blunt bow and stern have been made in Louisiana since the earliest colonial days. A variety of popular motorized applications have occurred in the century. One of the first was the Atchafalaya Basin bateau powered by a two-cycle, inboard "putt-putt" engine which served as the model T of swamp dwellers. Large inboard motors have been applied to a variety of flat boats. Many are used in the marsh as "mud boats" with air-cooled inboard motors which can churn through very shallow marsh trails or trainasses. Louisiana boatbuilders also found the flat boat compatible with outboard motors. A broadened transom and reduced length produced a Joe boat that would plane on the water with considerable stability.

European colonists introduced another small craft, the esquif or skiff. The Creole skiff, the only boat in North America rowed by a standing oarsman facing the bow, is an ancient form from southern France. Motivated by peculiarities of environment, changing need, and technological innovation, the skiff evolved into a myriad of variations.

The Lafitte skiff is particularly important in the Louisiana shrimp industry today. The construction of World War II P.T. boats in Louisiana inspired Louisiana boatbuilders to produce this shrimp trawler in the 18 to 35 foot class by adding a fantail transom, culling board, ice hold, and outrigger to the P.T.'s semi-V hull design, great sheer and flare in the bow section, and powerful inboard engine. Larger trawling skiff, 40 to 55 feet or more in length, are still built of cypress or Spanish cedar blanks.

A recent American introduction, the South Atlantic trawler, was brought in by Florida fishermen in 1937 after shrimp were discovered in deep water off the coast of Louisiana. These large boats, often 50 feet or longer with deep hull and forward cabin, are now commonly build of wood or steel along the Louisiana coast. Canots, the general French term for a ship's auxiliary craft, typically had rounded hulls, lug sails, an hour-glass transom, and a shallow keel. The canot sailed into the twentieth century as the famous New Orleans oyster lugger. After 1912, as the gasoline engine replaced the sail, the motorized oyster boats retained the name lugger and a hull design similar to the ancient canots.

This discussion barely introduced the complex and fascinating world of traditional Louisiana watercraft. The solid, historical tradition of boatbuilding in Louisiana is presently alive, viable, and moving into the future. Throughout Louisiana, traditional skills are being applied to a world of new materials, techniques, problems, and solutions.

For more information, the virtual exhibit, The Creole State: An Exhibition of Louisiana Folklife has images of these watercraft and other occupational crafts.

Wildfowl Carving

Wildfowl carving, also known as duck decoy carving, is widespread throughout Louisiana. This traditional craft has moved from being practiced solely in folk communities into mainstream communities. Many folk carvers conduct workshops and train new carvers from both within and outside of folk communities. As a result, it is difficult to decide if an individual is actually a folk craftsmen, revivalist, or contemporary craftsman. The carvers illustrate the difficulty of applying abstract categories to individuals. To complicate the matter even more, the craft is still evolving. Individuals are extending the traditional boundaries of the craft, researching the characteristics of exotic fish and fowl and their habitats. The carvings become personal artistic statements.

Even though crafts begin as functional objects, the functional value can become secondary to the aesthetic value. The tradition of duck carving in Louisiana is an example. The first duck decoys were originally crude facsimiles intended to attract flying fowl for hunters. But "as New Orleans Creole carver Charles Hutchison has commented, 'In the old days we used to catch birds with decoys, nowadays we mostly catch men'" (Spitzer 1985:135).

A variety of carving styles are found in Louisiana. Those following the older tradition carve ducks in a style and manner not intended to be realistic. Many are sleek without individual feathers indicated, and either have a natural finish or are painted in certain color combinations such as black and white. More recently, carvers are creating more realistic images of a wider variety of wildfowl. Some carve or burn each feather and paint the decoys realistically. Today, native and exotic water fowl, shorebirds, birds of prey, songbirds, and hummingbirds are carved life-size, half-size, and miniature. Full-size carvings may be in groupings, or placed in carefully researched habitats. The miniatures may be used as jewelry, and come complete with a stand which both protects the delicate items and creates an appropriate habitat. Some carvers also carve Louisiana's saltwater and fresh water fish, crawfish, exotic tropical fish, and other animals native to Louisiana. Native Louisiana tupelo gum and cypress are the most frequently used woods although basswood and other hardwoods are occasionally preferred.

For more information, the virtual exhibit, The Creole State: An Exhibition of Louisiana Folklife has carvings in the Decorative Crafts and Occupational Crafts sections. Contemporary and Revivalist Craftsmen.