Introduction to Delta Pieces: Northeast Louisiana Folklife

Map: Cultural Micro-Regions of the Delta, Northeast Louisiana

The Louisiana Delta: Land of Rivers

Ethnic Groups

Working in the Delta

Homemaking in the Delta

Worshiping in the Delta

Making Music in the Delta

Playing in the Delta

Telling Stories in the Delta

Delta Archival Materials

Bibliography

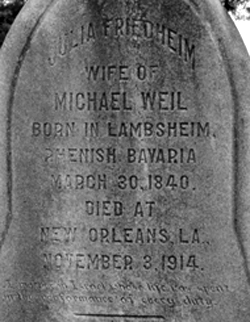

Jewish Folklore in Northeastern Louisiana

By Ben Sandmel

At first glance, Jewish folklore might seem to be an unlikely subject for presentation at a folklife festival in northeastern Louisiana. One reason is that the region does not have a large Jewish population. In addition, Judaism is a religion rather than a cultural or ethnic identification, and so any folklore found among a specific group of Jews is neither universal nor generic, but instead reflects such other factors as occupation, socio-economic level, or country of ancestral origin. For example, many foods that are thought to typify secular "Jewish cooking"--such as gefilte fish, borscht, etc.--actually reflect the broader food traditions of Eastern Europe. Jews who immigrated to America from other areas are not necessarily familiar with or fond of these dishes.

The practice of Judaism in America does not vary significantly from one part of the country to another, so no religious customs, beliefs or liturgical music can be considered unique to Louisiana. There are, however, some small but notable cultural variations which can be categorized as folklore. For instance, some Louisiana recipes for Jewish ceremonial food show the distinct influence of American southern cooking. One example is matzoh balls. These are made from matzoh meal, which is the unleavened flour used to bake the matzoh wafers that are eaten instead of bread during Passover. No observant Jew will eat any leavened bread or baked items during this holiday period. In most parts of America matzoh balls are served in soup. Although matzoh ball soup has become a popular year-round item in restaurants, in private homes it is usually only served at Passover.

But recent fieldwork shows that some Louisiana Jews do not regard matzoh balls as a special Passover dish. Caroline Masur, a Monroe resident who was raised in the predominately Cajun town of Napoleonville, in Assumption Parish, recalls that "when my father's bourré club came over to play cards, my mother always served them matzoh balls." Jean Mintz, a lifelong resident of Monroe, says, that "we served our matzoh balls as a side dish with gravy. They tasted a lot like dressing. We didn't put them in soup." Louis Caldwell, a current resident of West Monroe, offered this matzoh ball recipe:

Ingredients: 2 eggs, 2 tablespoons of oil or chicken fat, 2 tablespoons chicken broth, 1/2 cup matzoh meal.

Whip up the liquids, then stir in matzoh meal until it is just barely wet and refrigerate for 20 minutes. Form balls and drop them into boiling chicken broth and boil for 20 - 25 minutes.

It seems likely that further research will reveal additional instances of Jewish folklore in North Louisiana, especially in terms of recipes and craft traditions. It also seems likely that the majority of such folklore will be quite similar to that found in other Jewish communities throughout America with a few regional variations.

But there are other aspects of Jewish life in Louisiana which do not conform to the national norm; namely, the basic experience of being born and raised into Judaism in a part of the world that is outside the Jewish mainstream, and perceived by other Jews as such. In America, both Jews and non-Jews alike to tend to think of American Jews as residents of large cities, usually in the northeastern states. Many northern Jews are quite surprised to learn that Jewish communities exist in southern towns such as Monroe and have done so for generations. Accordingly, the most significant Jewish folklore to be found in northeast Louisiana may not be folklore per se, but rather the oral histories of the region's Jewish citizens, of which a brief sampling follows.

"I'd say that being Jewish is a pretty remote thing around here," comments 37 year-old Louis Caldwell, who was born in Vicksburg, Mississippi and raised in Tallulah, in Madison Parish. "I realized that early on when the kids in the neighborhood walked to church and we had to drive to Vicksburg to go to Temple. And I definitely encountered some prejudice and anti-Semitism. Kids at school would tell me I was going to be burned in hell, and they'd asked me why I killed Jesus. I didn't know how to respond. They'd also insist that I was rich and had buckets of money buried in the back yard, and I could never convince them otherwise. People were even more confused because I have an Anglo-Saxon last name."

"When I was young," Caldwell continues, "it was all verbal abuse, nothing physical. But in high school people would call me 'Jew' or 'dirty Jew' in a really derogatory voice. I defended myself quite adamantly then, and I was ready to scrap in a heartbeat if it was necessary, and sometimes it was. But in our Southern culture all you basically have to do is kick somebody's butt and then you have respect, and from then on you get along just fine and it's cool."

"Another thing I remember, Caldwell says, "is that we were starved for Jewish culture. If a production of 'Fiddler on the Roof' came to Jackson, Mississippi, we'd go see it every time. In my teens, I would go to a lot of National Federation of Temple Youth events around the South, so that I could meet other Jewish kids and learn about my culture. I'm raising my kids to be observant Jews, and I hope eventually they'll do the same." [Caldwell is also actively involved in another form of regional cultura l expression--African-American blues music--and will perform at the Louisiana Folklife Festival as the piano player with Tallulah blues guitarist Rufus "Rip" Wimberly.]

"It absolutely does take a lot of effort to maintain a Jewish identity in a town like Monroe," Jean Mintz recalls. "When I was growing up here, my twin sister and I often felt excluded, so it was good that we had each other. We went to Sabbath school on Saturdays, so we had to miss things like Girl Scout activities. And at that time, there were certain organizations and places like high school sororities and the country club where Jews were not admitted. Our mother taught us 'if you do not have res pect for your religion, then no one else will.' I was proud of my religion and when I grew older I knew that I wanted to marry within my faith, which I did."

"I never encountered any prejudice or anti-Semitism growing up in Napoleonville," Caroline Masur says. "Everyone was friendly. I had lots of Cajun Catholic friends, and sometimes I'd go to catechism with them. I was totally accepted. I'd have to say that there is prejudice in Monroe, just like there is in other places; I think David Duke's recent campaign for governor raised people's consciousness and made them aware of how much of that there is just below the surface. It made them see things more realistically."

"Something that concerns me," Masur says, "is that there doesn't seem to be much future for a Jewish community in Monroe. People don't turn out for cultural events, you have to be very careful that whatever you plan doesn't clash with a football game or a Halloween party or whatever. And Jewish kids are not staying here to raise their families. The best thing that's happened in the area is the opening of the Henry S. Jacobs camp over in Utica, Mississippi. They present a lot of cultural programs that my husband and I attend."

If North Louisiana's Jewish community is not flourishing at present--then it is all the more important that further research be conducted. This will preserve what exists and perhaps stimulate fresh interest in it. There is plenty of Louisiana Jewish folklore and oral history yet to be documented.