Cultural Catholicism in Cajun-Creole Louisiana

By Marcia Gaudet

Introduction

New Orleans musician and jazz legend Louis Armstrong was asked by a reporter if jazz was a form of folk music. His legendary reply was, "Pops, all music is folk music. I ain't never heard a horse sing a song." It might be said, as well, that all religion is folk religion. We do, however, recognize the differences between official doctrine and actual practice, particularly those "views and practices of religion that exist among the people apart from and alongside the strictly theological and liturgical forms of the official religion" (Yoder 1974: 2-15). Unofficial religious customs and traditions are certainly a part of Roman Catholicism as it is practiced by Cajuns, Creoles, and other groups in southern Louisiana who also practice the official, organized religion.

Don Yoder and other scholars agree that folk religion does not oppose a central religious body, but represents unofficial practices and ideas that have a dynamic relationship to official religion. As Amanda Banks notes, folk religion "includes those aspects that are often unsanctioned or not canonized by an official religion but are practiced as part of the religious experience" (Banks 1998: 216). Leonard Primiano, who feels that "folk" is a marginalizing term that sets it in opposition to "official" religion, has proposed the term vernacular religion instead for this type of religion, i.e., "religion as it is lived: as human beings encounter, understand, interpret, and practice it" (Primiano 1995: 44). As Primiano points out, even members of the religious hierarchy themselves are believing and practicing vernacularly (44-46). The "folk" are us.

In southern Louisiana, however, cultural Catholicism may be a better descriptive term, both because it avoids the possibly marginalizing connotations of "folk" and because it signifies the pervasive influence of non-official Catholicism in this region.

Southern Louisiana, unlike other areas of the South, is a place where Catholics are the norm, a region of cultural Catholicism-not only a religion as it is lived and practiced, but also as it affects the cultural beliefs, practices, worldview, and identity of the majority of the people. In the culture of the Cajuns and Creoles, the sacred and secular are often conflated. The Church and its rituals are central in the life cycle and throughout the calendar year-evident from Mardi Gras (certainly at the secular or profane end of the continuum) to All Saints Day (where the sacred is more privileged). The unifying potential of cultural communion and sacramental renewal is present in the rituals and secular sacraments of Louisiana's Cajuns and Creoles. An emotional connection with the cultural rituals as well as the official sacraments has colored their vision of the world.

Cultural Catholicism in Louisiana is not only a matter of theology. It is based on the traditional interactions and rituals of the Cajuns, Creoles of color, and others of European Catholic heritage-people who shared not only a common religion, but also a common region, heritage, and language distinctively different from the rest of the country.

My use of the term "cultural Catholicism" is not intended in the way that Kieran Quinlan uses it, distinguishing among Catholic novelists, "some of whom are 'cultural Catholics,' others true believers" (1996: 9). My use is based rather on the ideas of folk belief scholar David Hufford who uses the term to include both sacred belief and secular worldview and practice (Hufford 1994). Hufford stresses the cultural importance of Catholic tradition and devotional practices. He recognizes that some sacramentals are officially taught (like the rosary or the sign of the cross) and others are unofficial, what might be called "folk sacramentals" (such as the use of holy water, blessed candles, and blessed palms to protect a house during storms). Like the official sacraments and sacramentals, folk sacramentals are shared with a large community of people (1985:194-198).

In the introduction to God's Peculiar People, Elaine Lawless defines the folk church in contradistinction to the institutional church, and she focuses on folk religious practices in the context of Pentecostal groups who "establish themselves as a distinct folk group-through language and codes of behavior, and significantly, through dress codes for the female members . . . ." (Lawless 1988: 6-7). Cajun and Creole traditional religious practices do not, in themselves, set off those who practice such things as a separate folk group. Folk elements co-exist with official religion and the official sacraments and sacramentals are adapted and modified through traditional beliefs and practices. They incorporate folk elements without rejecting long standing official practices and beliefs. Lawless asks in relation to Pentecostals the critical question: "what in this religion is traditional—i.e. what is being passed down from generation to generation, or from group member to member, in an informal, largely oral manner?" (4). Cultural Catholicism among Cajuns and Creoles certainly has a wealth of traditional religious practices, but they function in conjunction with standardized official religion, not as part of a separate folk religion. In addition, cultural Catholicism in south Louisiana includes non-Catholics who participate in secularized Catholic rituals and who share some influences on their world view.

Sacraments and Sacramentals

Patricia Rickels's 1965 Louisiana Folklore Miscellany article, "The Folklore of Sacraments and Sacramentals in South Louisiana," deals with elements of folklore in Catholicism and focuses on the idea of the sacramental. It presents "a sampling of these para-ecclesiastical beliefs and practices, focusing on certain of the sacraments and sacramentals" (Rickels 1965: 27). Because of a lack of organized religious instruction and insufficient numbers of priests until the early 20th century, "certain naïve interpretations of complicated and subtle theological doctrines were developed . . ." (29).

While Canon law establishes a relationship between godparents and godchild that prohibits marriage between a godchild and a godparent, Rickels points out that other taboos have also been established through folk practice. One of these is that a godmother should not ask her own godchild to serve as a godparent to one of her children. This taboo is still known by Catholics in South Louisiana, but is probably not as generally observed as it was in the past. Other beliefs and practices that Rickels mentions, such as the taboo against sewing the baptismal gown on Friday or the belief that the baby must cry during the baptism ceremony, no longer seem to be important.

Rickels also notes that Catholic dogma at that time (1965) taught that unbaptized souls were excluded from Heaven and consigned to limbo. She points out the traditional belief in Louisiana that unbaptized souls wandered about as cauchemar (nightmare). It should be noted that though limbo has been discussed by theologians, the Roman Catholic Church has no official position on the subject of limbo. Cauchemar no longer seems to be directly associated with unbaptized infants, but the concept of cauchemar is still fairly well known.

Rickels defines sacramentals as "certain actions or things which have been blessed by the Church, in the hope that God will grant special graces to those who make use of them. They include the sign of the cross, holy water, blessed candles, palms, ashes, and oils; scapulas; vestments; medals; crucifixes; rosaries, prayers, and some other actions and objects" (33). She points out that these are often used for magico-religious purposes, rather than from the purpose intended by the Church. She notes, for example, that her informants used holy water to sprinkle around the bed at night (to ward off evil spirits) and to sprinkle around the house (to ward off storms).

Rickels says that blessed candles are "another sacramental widely used in the household rituals" to cure illnesses and to stop storms (35). Blessed palms that are blessed and distributed on Palm Sunday were also widely used in Catholic Louisiana to protect the house, particularly during bad weather.

The cross-either the sign of the cross or a material cross-was often used for religio-magical purposes. Again, it was believed to be important as a way of warding off storms or stopping rain. Making a cross out of two matches and then lighting the matches to stop the rain was a popular practice at one time. Rickels also mentions uses of the Rosary, in addition to its typical use in counting prayers (39). It was sometimes hung around the neck of sick children. In the 1980s, I heard the advice given in South Louisiana that putting a rosary around one's neck while flying would "keep the airplane from falling" from the sky.

Rickels says that special formulas for prayers were often used for special purposes, by repeating them a certain number of times or performing certain actions while saying the prayers (39). She also points out that certain prayers, when written down, were used as amulets (39).

Rickels states in conclusion to her 1965 article that "most of the traditions I have described are rapidly dying out" (42). While it is certainly true that these beliefs and practices are not as prevalent as they once were, folk Catholicism is not totally a thing of the past among Cajuns and Creoles. In fact, it is hardly possible to over estimate the influence of traditional Catholic practices and beliefs on Cajun and Creole culture. In a 1978 article, Rickels noted that the church's "sacraments and sacramentals, rituals, festivals, and observances of the ecclesiastical year, as well as its doctrines (sometimes imperfectly understood), provide a rich source of folkloric belief and custom. All aspects of life are permeated by this influence: the stages of life from birth to death, household routines and culinary practices, planting and weather lore, folk medicine, superstitions and taboos" (Rickels 1978: 246). For many Cajuns and Creoles, this continues to be true.

The important events in the lives of Cajuns and Creoles took place and continue to take place in the church-baptism, marriage, funeral. The church was and continues to be a binding force in the community-and, in fact, often defines the community.

The sacramental nature of Cajun-Creole Louisiana seems to include (indeed, to embrace) secular rituals and celebrations, along with the sacred, as part of cultural Catholicism. The Cajun-Creole brand of Latin Catholicism is characteristic of South Louisiana. Cultural Catholicism, like any complex tradition, continues to evolve to meet changing contexts and needs.

According to Rickels (1965), "the younger generation of Catholics tend to be orthodox and intellectual about their religion" but there are also para-ecclesiastical beliefs and practices that remain, not in opposition to official Catholicism but as an accepted part of Catholic culture in Louisiana (1965: 42). Some are clearly peripheral, practiced or believed by only a small number of Catholics. Others continue to be a central part of everyday life and belief.

Novena to Saint Clare, Statue of Saint Joseph, Saint Medard's Day

A peripheral practice, for example, is the personal publication of the Novena to Saint Clare nine days in a row in the Lafayette daily newspaper, The Advertiser. This has gone through several cycles, particularly popular in 1995 and 1996. The novena consists of saying nine Hail Mary's and the following prayer for nine days in a row: "May the Sacred Heart be praised, adored, glorified and loved today and everyday throughout the world forever. Amen." The instructions, included in the newspaper ad, are then to publish the prayer in the newspaper on the ninth day with the belief that "your request will be granted whether you believe or not" no matter how impossible it may seem. This novena is now on several web sites on the internet as well, though I could find none from Louisiana. One of the web sites instructs, "Ask Saint Clare for three favors, two impossible, and say nine Hail Mary's and the following prayer for nine days with a lighted candle."

Some of the practices may even be called whimsical. For example, there is the popular practice of using statues of Saint Joseph, buried up side down in a yard, to assure or hasten the sale of a home. It is unclear where this practice originated, but it is definitely known and practiced in southern Louisiana. I have been told that some realtors keep statues of Saint Joseph in their offices in case a client requests one. One of my students told me about a new homeowner in Lafayette getting a call from the former owners, asking them to dig up the statue that had been buried in the yard. This practice is known in other areas of the country as well. Since Saint Joseph was a carpenter as well as the Patron Saint of Families, it seems fitting that he should have a role in the sales of homes.

There is also the belief among the older generation of Cajuns that if it rains on June 8th, Saint Medard's Day, it will rain for forty days. Saint Medard was a sixth century French bishop, and this belief among the Cajuns is analogous to the weather forecasting beliefs about Saint Swithin's Day (July 15) in England. This is certainly still known in southwestern Louisiana as well as near New Orleans. A few years ago, a television weather reporter in Lafayette presented a version of the weather prognostication beliefs associated with June 8th but instead of relating those beliefs to a saint's legend, he gave the spelling as "Samidar," a phonetic spelling of the French pronunciation of Saint Medard.

Yard Grottoes

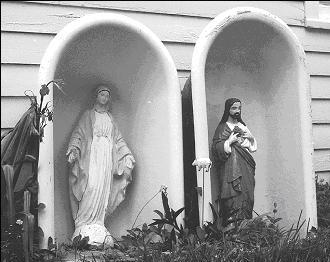

Yard grottoes (small religious shrines) honoring the Virgin Mary, the saints, and Jesus, particularly the Infant Jesus of Prague, are still extremely popular among Cajuns and Creoles throughout southwest Louisiana. Various settings are used to display the statues and various materials are used to construct the grottoes-including grottoes fashioned from half of an old-fashioned bathtub in Basile and various other places. There is a double "bathtub grotto" in Thibodaux, where both halves of the bathtub are used, one with a statue of the Virgin and the other with a statue of the Sacred Heart (see Figure 1). More typically, grottoes are homemade of brick, stone, or wood designed to protect and partially enclose a religious statue. Yard grottoes are sometimes part of a complex of yard decorations that include both sacred statuary and secular sculptures. One yard in Choupic, Louisiana, has a Virgin in a front yard display that includes several pink flamingoes.

Figure 1. Yard Grotto in Thibodaux.

There are a remarkable number of yard grottoes throughout southern Louisiana. They seem to be especially popular among older women who often plant flowers near the grottoes. While most grottoes are in the front yards of homes, visible from the street, it is unusual to see a front yard grotto used as a place for prayer. Some families choose to build a grotto in the back yard for a more private place of devotion. Families who construct a grotto or simply have a statue of the Virgin Mary in their front yard are making a public statement of their Catholic faith, and they are typically devout, practicing Catholics. I have also been told that having a grotto in the yard will keep proselytizers of other faiths away.

Yard grottoes, particularly statues of the Virgin, are not unique to Cajuns and Creoles, but seem to be a part of heavily Roman Catholic expressive cultures. For example, Joseph Sciorra has documented the large number of yard shrines and sidewalk altars in New York City's Italian American neighborhoods. He says, "Thus, the Sacred Heart and the Immaculate Conception keep company with concrete stableboys, stucco dwarves, plastic cartoon characters, and a menagerie of artificial flamingos, ducks, rabbits, and deer" (Sciorra 1989: 185). Sciorra also includes a photograph of a shrine to the Blessed Virgin Mary built around a discarded bathtub in Brooklyn (reminiscent of shrines found in rural Italy), thus suggesting an aesthetic of yard shrines much like those in southern Louisiana (187).

Traiteurs

Roman Catholicism has consistently emphasized a relationship between healing and the power of prayer. Traditional healing has always been associated with belief as well. Among Cajuns and Creoles there is the continued use and popularity of folk healers or treaters— called traiteurs —who believe their gift of healing is a blessing from God and an integral part of their Catholic faith (see, for example, Daigle 1991). Traiteurs are faith healers who sometimes use herbal medicine as well as prayers and rituals to heal. They can be compared to the Mexican curanderos or the "pow wow" healer of the Pennsylvania Germans. Traiteurs can be male or female, and they have various beliefs about how they obtained their power to heal. They do not advertise, and they do not charge a fee. All believe that they are intermediaries of God and that their Catholic faith is essential to their power to heal. They use special prayers as well as blessed candles, holy water, or religious objects and gestures (especially the sign of the cross). Typically, they are not in conflict with physicians, but treat those ailments (usually none life-threatening) that are not worth going to a physician to treat—or that physicians have been unsuccessful in treating, e.g. warts, arthritis, asthma, a pulled muscle. Most traiteurs have other full–time jobs or work at home. For example, Mr. Lousay Aubé of Meaux is a retired high school teacher who has treated people in his community and others who drove from Lafayette for his treatments. Mr. Aubé is a "broad spectrum" traiteur, treating for many different ailments. He is also a devout Catholic, and like most traiteurs, sees no conflict between his powers to heal and official Catholicism.

Bonne Mort Society

The Bonne Mort Society of Carencro, Louisiana, a pre–Vatican II relic, is still active in a small, primarily Cajun, Catholic church parish in southwestern Louisiana. In a recent Louisiana Folklore Miscellany article, Julie Landry says that the Bonne Mort (literally "Good Death") Society of Saint Peter's Catholic Church in Carencro was founded in 1906 by a French priest who was then pastor of Saint Peter's. According to Landry, "the original name of the organization was the Bona Mors Confraternity. . . founded in Rome in 1648 by Friar Vincent Carafa, the seventh general of the Society of Jesus, apparently to help people to prepare for death from the plague that swept Europe so often in that century" (Landry 1998: 4). The organization's charter limited the founding of chapters to Jesuit church parishes. Landry also found that Friar Grimaud, the founder of the local group, was indeed a Jesuit, and Carencro was a Jesuit mission in 1906. The Jesuit historian at Saint Charles College in Grand Coteau, Friar Rogge, was "as astounded as the diocese archivists to find that such a group was still in existence" (4). Landry reports that according to the president of the Bonne Mort Society, Saint Peter's chapter in Carencro had seventeen–hundred members in 1998. The dues are $2 for a new member and $1 yearly thereafter. The Catholic Encyclopedia says that the purpose of the organization was "to prepare each member, through a spiritually disciplined life and a special devotion to Christ's Passion and the sorrows of Mary, for a peaceful death" (qtd in Landry 1998: 5). Carencro's chapter was authorized by the Archbishop of New Orleans (Lafayette did not have its own bishop until 1918) and its stated purpose was "the deliverance or lessening of the sufferings of the souls in Purgatory through the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass." Several things have changed since the original charter, including an emphasis among members under sixty years of age on the benefits of prayers for the living—not only after death. Officers today are the president and the treasurer. According to Julie Landry, "No elections are held. When one person tires of a position, she hands it to the next willing person" (8).

Pilgrimage Sites

Pilgrimages to sacred sites have long been popular with Louisiana Catholics. In the 1950s and 1960s, pilgrimages to the Shrine of Saint Anne de Beaupré in Québec, Canada, were extremely popular. In the early 1990s, large numbers of Catholics from southern Louisiana made the pilgrimages to Medjugorje to visit the site of the alleged apparition of the Virgin in the former Yugoslavia. There are several sites in Louisiana that are considered sacred by some Catholics, and they have become well–known destinations for pilgrims and tourists. Two of the best known are the tomb of Charlene Richard in Richard and the Shrine to Saint John Berchmans in Grand Coteau.

Charlene Richard, a young Cajun girl who died of leukemia in 1959, is regarded by many in south Louisiana as a saint. Thousands have made pilgrimages to her grave in Richard, Louisiana (a small farming community 35 miles northwest of Lafayette), though there has been no official recognition or investigation by the Catholic church. Because of the beliefs associated with Charlene, she has become what might be called an uncanonized saint— also known as a folk, local, or indigenous saint.

While local devotion to many folk saints began during their lifetimes because of religious work or healing, this was not the case with Charlene. Unlike many other folk saints, Charlene had not been the object of devotion or a folk heroine during her lifetime. The stories, veneration, and cult formation regarding Charlene seem to have originated with personal narratives about Charlene told mainly by the nun and priest who attended her at Our Lady of Lourdes Hospital in Lafayette during the days before her death. Stories of her bravery in the face of certain death and her "offering up" of her suffering for others soon spread, with tales of miraculous intercession for both healing and temporal favors. The cult of devotion to Charlene formed quickly and her grave in Richard, Louisiana, became a pilgrimage site.

The effect of print and the media on this folk saint's legend is evident. By August 1989, the thirtieth anniversary of Charlene's death, thousands were visiting her grave every year, some individually, others in organized tours. At that time over five–hundred thousand prayer cards with a "Prayer to Charlene Richard" had been distributed and an organization, Friends of Charlene, was formed. Since then, thousands have made pilgrimages to Charlene's grave in Saint Edwards Cemetery in Richard, and the highway, previously designated with only a number, has been named Charlene Richard Highway. People continue to leave ex voto on Charlene's grave, and many light votive candles, still very popular in rural areas of south Louisiana and available in the church, to Charlene. The beliefs, stories, and local devotion to Charlene reflect a basic worldview of the culture of the Cajuns and Creoles in south Louisiana. Though people disagree on whether Charlene is really a saint, in times of need they are quite willing to pray to her— just in case she is a saint. This is typical of the practical attitude of Cajuns about life in general. They certainly think of themselves as followers of official Catholicism, but they see no problem or conflict in also availing themselves of the less official beliefs and practices of folk sacramentals (See also Gaudet 1994).

The Academy of the Sacred Heart in Grand Coteau was founded in 1821, the second oldest school west of the Mississippi River. It has remained in continuous operation as a school for girls. According to the Catholic Church, it was also the site of a "miracle" in 1866. A young novice, Mary Wilson was seriously ill. According to a Saint Landry Parish Tourist brochure, "She offered a novena to John Berchmans, a Jesuit priest from Belgium who had died at an early age. She was cured after having a vision of this priest, and subsequently this "miracle" led to his canonization." The Shrine of Saint John Berchmans, erected at the place where the miracle occurred, is opened to visitors. Mary Wilson died at Grand Coteau in 1867 and was buried in the graveyard on the grounds of the Academy. Her grave is also a popular pilgrimage site (see Figure 2). Both the Shrine of Saint John Berchmans and Charlene Richard's grave are listed in The Top 50 Tourist Attractions of Cajun Country (Angers and Sullivan, 2001), listed as "The Miracle of Grand Coteau Site & Academy of the Sacred Heart" (31) and "Tomb of Charlene Richard, 'The Saint from South Louisiana'" (18).

Figure 2. Mary Wilson's grave marker in graveyard at Academy of the Sacret Heart, Grand Coteau.

Another site in Louisiana that is believed to be sacred by some Catholics is the Shrine of "Our Lady of Tickfaw" in Tickfaw, Louisiana. The site of an alleged apparition of the Blessed Virgin on March 12, 1989, on the property of Alfredo Raimondo near Tickfaw (1 1/2 miles from I–55, about 50 miles north of New Orleans), it is located in an area of Louisiana that is primarily Protestant, not the French Catholic Cajun/Creole area of southern Louisiana. While it reportedly draws thousands of pilgrims each year, it does not seem to be a popular pilgrimage site for Cajuns and Creoles from southwestern Louisiana.

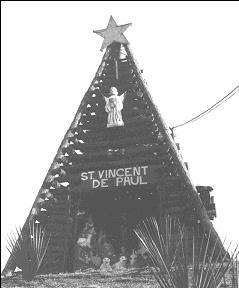

Saint Vincent DePaul Bonfire

The tradition of lighting Christmas Eve bonfires on the levees of the Mississippi River between New Orleans and Baton Rouge has been popular since at least the late nineteenth century. A more directly religious dimension to the bonfires began in the late 1980s with the building of bonfire pyres incorporating a creche. The nativity figures are placed inside the pyre and removed before the bonfire is lit on Christmas Eve. The most significant of these is the Saint Vincent DePaul Bonfire, built each year since 1990 in Lutcher (see Figure 3). Saint Vincent de Paul is the patron of charitable societies, and many Catholic churches have a collection box in the back of the church for charitable donations. Saint Vincent de Paul was born in France in 1581. He worked with the poor in Paris, and founded the Daughters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul (sometimes called Sisters of Charity). The Saint Vincent de Paul Society continues to work for the benefit of the poor. It is interesting to note that Daughters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul have served as nurses, caretakers, and administrators at the National Hansen's Disease Center (originally the Louisiana Leper Home and later the National Leprosarium) since 1896, two years after it was established, in Carville, Louisiana. Carville is also on the Mississippi River, about 25 miles north on Gramercy. Though the hospital at Carville was officially closed in 1999, there are Daughters of Charity who remained there to run the Carville Trautman Museum, dedicated to documenting the history of Carville and its people.

Figure 3. Saint Vincent de Paul bonfire crèche, Lutcher.

In the pamphlet distributed at the bonfire, there is a picture of the bonfire surrounded by children, a history of this particular bonfire's origins, and the personal testimony of Leonard J. Bivonia, who is the organizer and builder of the Saint Vincent DePaul Bonfire. He explains his motivation for building a bonfire to honor Saint Vincent DePaul:

- In December of 1988, I was taking pictures of the bonfires in Gramercy. I noticed that one of them had an opening cut out. Inside was a small nativity scene. When I saw that, an idea came to me.

- I wanted to build one, but on a larger scale. Throughout 1989 I thought about it more and more. In 1990 something said do it. I talked to four other men and decided to build the bonfire. . . . I believed this bonfire belonged in front of a church. At that time I went to talk to my parish priest at Saint Joseph. Because of the problem it may cause with the traffic going to evening mass we decided not to build it there.

- Since I am a member of the Saint Vincent DePaul Society, I asked the president, Pete Roussel, if I could build it in front of his house in Lutcher. The bonfire was built in two or three days. I stayed on the levee for two weeks, playing religious songs and giving out candy to the children. One day something told me to turn around. When I turned around, to my surprise, I saw a beautiful sight. Our Lord Jesus, had put the bonfire in front of Saint Philip Catholic Church, just across the river [in Vacherie]. (Bivonia 1995)

In the pamphlet, Mr. Bivonia also relates an experience in 1990, where a man unknown to him was at the site at 2:00 A.M. Christmas morning, picking up the logs and cleaning the site. He believes this may have been a "divine intervention." There is also a "souvenir" miniature bonfire for sale, modeled on the Saint Vincent DePaul pyre, with a creche inside illuminated with a red light.

Hurricane prayer card

Hurricane warnings for southern Louisiana typically set into motion not only the practical preparations (stocking up on candles, water, food, etc.), but sacramental traditions for protection from danger. These include displaying blessed palms in the house, sprinkling holy water around a house, and lighting blessed candles. There are prayers, as well, for protection from storms, some printed on cards for distribution at the church during hurricane season (June 1 through October 1). The following is from a Hurricane prayer card that John Laudun, a colleague of mine here at the university, brought from Our Lady of the Rosary Catholic Church in Jeanerette, Louisiana (printed on light blue card, two by eight inches):

LET US ASK GOD

TO HELP US

DURING THIS

HURRICANE

SEASONFather, all nature

obeys your command.We ask you to calm

the storms that

threaten our well being.

Turn our fear of the

power of nature into acts

of praise of your goodness.

We pray in the Name of

the Father, and of the Son

and of the Holy Spirit.

AMENMary, Star of the Sea,

Pray for us.

OUR LADY OF THE ROSARY

Jeanerette, Louisiana

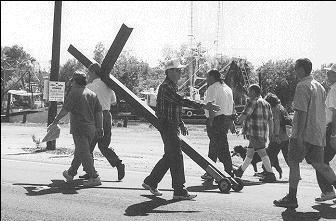

"Living Way of the Cross" in Dulac

The "Living Way of the Cross" is an annual Good Friday procession on Grand Caillou Highway in Dulac, Louisiana. This event involves pastors from three different churches, including the Catholic church, carrying the cross. A notable feature is that the cross has wheels on it, somewhat like "training wheels" on a bicycle, so it glides easily down the highway. The procession begins at a Protestant church and arrives at the Catholic church shortly after the traditional "Way of the Cross" has ended. Escorted by two police cars, it is ecumenical as well as decidedly informal. The priest, dressed informally and (in 2000) wearing a red baseball cap, then carries the cross to the next church. A crowd of about thirty people and a few dogs follow the cross on foot or on bicycles, waving to people along the way and even taking a break to run in Boudreaux's Super Market to buy soft drinks or beer (see Figure 4). In spite of the informality, this is still perceived as a sacred event, and due the same concessions from motorists that are extended to funeral processions or other solemn events, particularly when the procession stops from time to time to observe the "stations" of the cross and to pray. When a car passed the procession, I overheard one elderly woman along the route say, "Some people don't have no respect."

Figure 4. Good Friday "Way of the Cross" procession in Dulac.

Conclusion

Folklorist David Hufford has pointed out the complex relationship between official teachings and semi–official beliefs and practices. Like the official sacraments and sacramentals, such as the rosary or the sign of the cross, there are the other, unofficial actions which might be called "folk sacramentals." Like the official sacraments and teachings, the unofficial actions and beliefs are shared with a large community of people. Though they are unofficial, they exist in tandem with official religion and they are sufficiently well–known and practiced to indicate wide–spread tradition. They express membership in the group, and are often a means of making visible and meaningful what is perceived as the distant, abstract theology of official religion. As Amanda Banks has noted about folk religion, in general, "Integrally connected to group membership, such folk beliefs and practices interpret and give meaning to the dogma and ritual of official religion within the daily lives of practitioners and believers" (Bank 1998: 216). Cajuns and Creoles, in general, are practical people not particularly given to abstraction. While some of the traditional practices of Catholics in Louisiana may seem strange—and even provoke humor at times—they are grounded in a foundation of solid (and often unquestioning) faith. They are a manifestation of commitment to traditions and beliefs of Catholicism as practiced in Louisiana. Cultural Catholicism in Louisiana is clearly not opposed to official Catholicism, but remains a vital and meaningful part of religious practice and belief.

Sources

Angers, Trent, and Dennis Sullivan, eds. 2001. The Top 50 Tourist Attractions of Cajun Country. Lafayette, LA: Acadian House Publishing.

Banks, Amanda Carson. 1998. Folk Religion. In Encyclopedia of Folklore and Literature, eds. Bruce Rosenberg and Mary Ellen Brown, 216–17. ABC–Clio.

Bivonia, Leonard J. 1995. The Saint Vincent DePaul Bonfire: Divine Intervention or Coincidence? np. [privately published pamphlet].

Daigle, Ellen M. 1991. Traiteurs and the Power of Healing: The Story of Doris Bergeron. Louisiana Folklore Miscellany 6 (4): 43–48.

Gaudet, Marcia. 1994. Charlene Richard: Folk Veneration among the Cajuns. Southern Folklore 51 (2): 153–66.

Hufford, David J. 1985. Ste. Anne de Beaupré: Roman Catholic Pilgrimage and Healing. Western Folklore 44: 194–207.

_____. 1994. Ethical Issues in Studying Folk Beliefs and Folk Religion Forum. Presentation at the American Folklore Society Meeting October 22, in Milwaukee.WI.

Landry, Julie. 1998. The Bonne Mort Society of Carencro, Louisiana: A Post-Vatican II Relic. Louisiana Folklore Miscellany 13: 3-13.

Lawless, Elaine. 1988. God's Peculiar People: Women's Voices and Folk Tradition in a Pentecostal Church. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky.

Primiano, Leonard Norman. 1995. Vernacular Religion and the Search for Method in Religious Folklife. Western Folklore 54: 37-56.

Quinlan, Kieran. 1996. Walker Percy: The Last Catholic Novelist. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press.

Rickels, Patricia. 1978. The Folklore of the Acadians. In The Cajuns: Essays on Their History and Culture, ed. Glenn R. Conrad, 240-54. Lafayette, LA: Center for Louisiana Studies.

_____. 1965. The Folklore of Sacraments and Sacramentals in South Louisiana. Louisiana Folklore Miscellany 2 (2): 27-44.

Roberts, Katherine. 1998. Contemporary Cauchemar. Louisiana Folklore Miscellany 13: 15-25.

Sciorra, Joseph. 1989. Yard Shrines and Sidewalk Altars of New York's Italian-Americans. In Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture, III, eds. Thomas Carter and Bernard L. Herman, 185-98. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press.

Yoder, Don. 1974. Toward A Definition of Folk Religion. Western Folklore 33: 2-15.