The Public and Private Domains of Cajun Women Musicians in Southwest Louisiana

By Lisa E. Richardson

Until the women's movement brought gender issues into the limelight, the course of music history was often presented as an exclusively male domain. Women's role in creating, shaping, and performing music was largely overlooked. But within the past twenty years, women's music that was previously unknown to researchers, or undervalued and taken for granted by cultural insiders, has increasingly piqued interest. This rediscovery has yielded some unexpected and illuminating results for all involved.

The traditional music of Southwest Louisiana's Cajun culture has also exploded into national attention within the past twenty years. Although most of the publicly accessible music is composed and performed by men, some Cajun women participate both in the private, home-based musical tradition and in an increasingly audible public side.

The Private Domain of Cajun Music

Since the time of the Grand Derangement when the Acadians were expelled from Nova Scotia, there have been French Louisiana songs and ballads which were sung, usually unaccompanied, for pleasure within the home among family and friends. Older relatives taught these songs directly to the younger generation, or children picked them up as they were performed as entertainment during family soirées. These include songs that recall the terrible hardships of the trip from Acadie, social drinking songs, call-and-response children's songs, and humorous epics about the various predicaments of romantic love. These "home songs" are basically a separate repertoire from Cajun dancehall music, although some dance band pieces naturally cross over into the private domain.

Various aspects of home songs, such as their rhythmic subtlety, subject matter or length, make them more appropriate for intimate performances than for performances with a band at large gatherings. For example, many of these songs are in modes other than the usual major or minor, or may change mode mid-song—something a band does not usually do. Since these were usually solo performances, singers could take rhythmic liberties and stretch out or quicken a phrase according to their feelings. These were songs to be listened to rather than danced to, so the poetry was in some cases more elaborate and descriptive and the songs were often longer than their counterparts in the dance repertoire.

One genre of traditional songs provided a link between the dance band and home songs: the "reels a bouche," similar to Celtic "mouth music." These were tunes that were sung to accompany round dances during Lent when instrumental performances were not allowed. The verses and meters of these pieces are generally simpler than those of the home music, but they are still a more private mode of expression than the dance hall numbers.

Both home songs and round dance songs were orally transmitted. The only people who learned these pieces were those who had the opportunity to hear them in person repeatedly, usually from a relative. In this way, the songs were given a kind of personal ownership within families. For instance, Tante Emedine might sing the epic love song "Isabeau," one or two musically inclined nieces might learn it, and although other versions may exist, no one outside of the extended family would know it in quite the same form. The shared knowledge of these songs acted as a glue which strengthened family and cultural bonds.

Although women dominated the home music repertoire, it was not always exclusively their domain. Older performers in their 70s and 80s have cited many examples of men enthusiastically joining in the singing of home songs, although not as often as women. Unfortunately, members of this older generation of singers were rarely documented during their lifetimes. Today, however, some men, like Sullivan Aguillard of Oberlin, continue to sing traditional ballads and help to keep the tradition alive.

Social pressure has played an important role in women's performance of music. Cajun men have always had the option of public performances without risking much social stigma. Women, on the other hand, have usually been emphatically discouraged, in both subtle and overt ways, from bringing their musical talents into a public arena. This may be one reason that the home songs flourished particularly among women as an outlet for artistic expression. Cajun women have, more often than not, chosen to express their musicality in the most socially acceptable manner available to them, among family and friends.

These home songs provided both entertainment and a way of reciting oral history. With the advent of mass media, however, these purposes began to fade in importance. Unlike dance music which thrived along with the phonograph and radio, home songs' popularity declined as technological advances offered new possibilities for entertainment in less time-consuming, less energy-taxing ways. Only as these songs have teetered on the edge of extinction have they begun to receive the attention they deserve.

Up until around the 1930s to 1950s, the home songs and the dance hall songs existed as complementary repertoires within the culture — the home songs acting as an ancient base anchoring Cajun culture in the past and providing some material upon which modern Cajun composers could draw. It seems this anchor is slipping away with each passing generation. Perhaps these songs are no longer relevant to modern life in the context in which they were originally performed.

Some notable women performers, however, have continued the tradition of home music, sometimes bringing their songs into the public arena through recordings and performances at festivals. For example, the late Lula Landry of Abbeville had an incredible repertoire of home songs, most of which she learned before the age of 15 from her Tante Olympe who would sing to Lula during their catechism lessons. Lula was a musical sponge and could learn a piece on first hearing no matter who or what the source was. In fact, her husband's big band used to use her as a human tape recorder when they went to clubs to hear other bands. On the way home, Lula would sing the tunes that they had heard that evening to the members of the band, and in this way they could learn new pieces without having to invest in sheet music.

Inez Catalon is a Creole woman from Kaplan and is another wellspring of home music with a repertoire and a style completely different than Lula's. Inez learned many of her songs from her mother at the hearth of their home— the same home Inez resides in today. Inez is a chameleon of style. Not only can you hear her mother's heart wrenching voice through hers, but she can also become the voice of Jimmie Rodgers and many of the popular radio stars of the early part of this century. Inez is a vibrant t ell-it-like-it-is character with a wealth of music, jokes, and stories within her.* (Inez died in November 1994).

Other cultures, such as those in Bulgaria and England, have rescued much of their time-honored music from extinction by reinterpreting it for modern society and reclaiming it as their own. Perhaps families no longer have the inclination to entertain each other with song. But the lyrics—about love, pain, loss, struggle, joys—are still pertinent to modern life, and the melodies, with their modal complexities and non-standard meters, are still as beautiful as ever. It is time to unearth this buried treasure. Today, there is an increased interest in women singers and their home-based music. For example, Ann Savoy's upcoming Volume 2 of her series of books on Cajun musicians will focus on women performers.

The Public Domain

Historically, Cajun women have been discouraged from public performance. According to many men and women in French Louisiana, the dance hall stage of the past was not considered a place for "decent" women to be. As has been the case in many other societies throughout time, certain false assumptions and misconceptions have arisen concerning the morals of women who perform in public. There have been exceptions, the most famous of which is Cleoma Breaux Falcon who performed with her husband Joe Falcon from the late 1920s until her death in 1941. She was a curiosity, yet she was considered "safe" since she was with her husband.

Only in recent times have women ventured into the spotlight to be the center of a group's attention on a solo instrument, or even the leader of a group instead of an innocuous part of the whole. Becky Richard, for example, is a young Cajun guitarist and singer from Church Point who has regularly performed with her accordionist father Pat over the past several years. It was actually Becky who was the motivating force behind reviving her father's musical talent. She convinced him to dust off the accord ion in his closet and join her in performing the music of their heritage. Becky has a beautiful, soulful voice and a talent for songwriting.

Cankton accordionist Sheryl Cormier has been a pioneer for the cause of Cajun women's public performance for years. She is a powerful and exciting performer who was a natural on her instrument at an early age, a talent she believes was inherited from her father. In the mid-1980s, she formed the first all women's Cajun band. Since then she has been the leader of a band including her husband, Russell on vocals and their son, Russell Jr. on drums.

Guitarist and singer Ann Savoy, although not a native of Acadiana, is another champion of Cajun music, not only on stage but on paper. She performs across the country at festivals and in clubs with her husband, Eunice accordionist Marc Savoy, and is also the author of the book Cajun Music: A Reflection of a People. The Savoys prefer to perform a style of Cajun music older than the styles used by many of the dance hall bands of today. They usually choose to perform in a trio format of accordion, guitar and fiddle, and avoid electric instruments altogether.

The women performers of Cajun music have struggled with their art - struggled to be taken seriously as musicians and struggled through the suspicions of others. Through this struggle they are paving the way, hopefully, for future women performers to follow the path that they have opened.

Bibliography

Savoy, Ann. 1984.Cajun Music: A Reflection of a People. Eunice, LA: Bluebird Press.

Discography

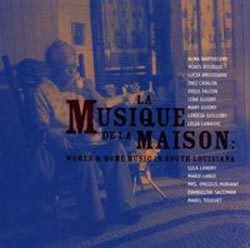

If you would like to hear some examples of home-based music, recordings are available of the following women:

Inez Catalon. On "Zodico: Louisiana Creole Music" (Rounder Records); "Louisiana Creole Music" (Folkways Records). Agnes Bourque. "J'Etais au Bal: Music from French Louisiana" (Swallow Records).

The Hoffauir Family and Others. "Louisiana Cajun and Creole Music 1934: The Lomax Recordings" (Swallow Records). Odile and Solange Falcon. "J'ai Ete au Bal, Vol.1" (Arhoolie Records).

Recordings of women dance hall performers include:

Becky Richard. Several 45's on Lyric Records. An album is due out.

Sheryl Cormier. "La Reine de Musique Cadjine" (Swallow Records).

Ann Savoy. Many recordings with the Savoy-Doucet Cajun Band (Arhoolie Records).

Zydeco recordings of female performers include:

Ann Goodly. "Miss Ann Goodly and the Zydeco Brothers" (Maison de Soul).

Queen Ida. "Queen Ida and the Bon Temps Band in New Orleans", "Zydeco a la Mode" and "Zydeco" (all on GNP Crescendo).