The Folk Etymology of the Fais Do-Do: A Note

By Joshua Clegg Caffery

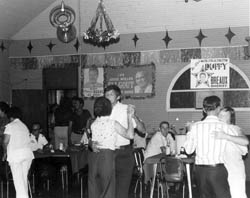

By most accounts, the term fais do-do (with do pronounced dough) , in contemporary Louisiana parlance, refers to a public dance of some sort, often one held on a Sunday afternoon, usually involving an accordion and fiddle-led band and lyrics sung in vernacular Louisiana French. Indeed, the fais do-do is one of the first things visitors to French Louisiana learn about, along with a quaint story about how the expression evolved out of the practice of aged relatives lulling babies to sleep in the parc aux petits, a room reserved for sleepy infants in the back of Louisiana dance halls (like a cry room in Catholic church, but meant to isolate the baby from the noise, rather than to isolate the grownups from the babies' noise). I have heard this explanation given countless times, and I admit to even using it myself in the past, for lack of a better one. But where does this explanation come from, and is it correct? It certainly makes for a good story, and it makes sense (in a way), but there other possibilities. In this note, I argue that the familiar sleeping baby definition is most likely a folk etymology, and I offer an alternative hypothesis for consideration.

Like much folklore, the sleeping baby etymology of the fais do-do is usually reported as anonymous hearsay, even in books, articles, and scholarly reviews. This definition has become so ingrained that writers (much less tour guides) feel no compunction to cite a source for this information, and hence it is related as apodictic truth (for instance: Hallowell 2003:76; Karlin 2009:138; Mitcham 1992: 15; Gutierrez 1996:467). Surely, we might ask, Alcée Fortier or some other eminent nineteenth century folklorist figured this out long ago, and it has rightfully become accepted as fact? As it turns out, however, this is not exactly the case. Rather, it seems that writers, folklorists included, have uncritically accepted the etymology as given by community scholars and informants (see Lindahl et al. 1997: 148 for an example of the etymology gleaned from an interview and presented by the editors as fact). These sources, however, are simply repeating the same apocryphal explanation known by almost anyone who lives in Southern Louisiana. The originator of this explanation, however, remains anonymous, despite its popularity. Sometimes the matter is complicated by a link to the song "Fais Do-Do, Minette," one of innumerable French songs that include the injunction, "fais do-do." Sometimes the mother lulls the baby to sleep, sometimes an elderly grandmother or Creole nanny. In other words, the scene, which seems almost drawn from a late nineteenth-century local color feature story, is both variable (in the telling) and anonymous (in its origins)— common marks of folklore.

Does this explanation truly make sense, though? To some extent, it seems very plausible, even probable. These words do occur in songs that were well-known at one time, and mothers and grandmothers to this day "do-do" their babies to sleep ("do" from "dors," stemming from the imperative of dormir, to sleep). It is quite a leap, however, from an action done to soothe a baby, to an adult activity so very different from soothing a baby. Parents put babies on hush mode at any number of locations using such techniques: the home, of course, the homes of relatives, or (as I said before) church, or while riding in the back of a car. Would it have been as likely to designate Catholic mass the "fais do-do," because babies are tranquilized in a sequestered baby area meant for the same purpose? Mothers "do-doed" and continue to "dodo" their babies constantly, without regard to location. As the saying goes, there is nothing as wonderful as a sleeping baby, and a public dance is only one of a practically infinite series of desirable slumbering baby situations. In my own experience, babies tend to like the ambient noise of public places, particularly public places filled with fairly loud, rhythmic pulses, and it strikes me that a baby would be as likely to "dodo" on the dance floor as in an isolated baby area. When asked what they would be doing over the weekend, did young adults once really say, in so many words, we're going to "make the baby go to sleep"? Possibly.

There is another explanation, however, that has been overlooked. In various folk dancing traditions throughout America and Europe, the contra dance call/step dos-à-dos, from the French meaning "back to back," gave rise to a diversity of vernacular terms. For instance, in Western square dancing, dos-à-dos transmuted into "dosado," and remains a popular dance step and call to this day. In fact, www.dosado.com is the central online hub for contemporary Western square dancing. Similarly, in English, "dos à dos" became "do si do," a familiar call retained in a number of Anglo-American folk songs and dance traditions. In all cases, the call means virtually the same thing: approach your partner and circle around each other, back to back. Contra dance, particularly in the form of quadrille, was as popular in Southern Louisiana as it was in Western, New England, and Appalachian dance traditions, and it antedated the more contemporary Cajun/Creole accordion-driven, two-step and waltz dances more familiar to modern observers (in Louisiana Creole, the word was kadril). Early "Cajun" musicians, such as Dennis McGee, not to mention many early Creole jazz musicians, cut their teeth playing for quadrilles before the more simplified couple dances took over (Daigle 1972; Fiehrer 1991; Szwed and Morton Marks 1988). My alternate theory is that "fais do-do" was a vernacular Louisiana French expression, derived from a call, based on "dos à dos." It would be strange if no vernacular Louisiana version of "dos àdos" existed, to begin with, even though vernacular descendants from the French exist in Western and Appalachian traditions. In other words, "dos à dos" is such a basic and common call in the broader world of vernacular and creolized contra dance that it generated a host of descendants—why not a Louisiana cognate? Furthermore, when seeking to derive an etymology for "fais do-do" as a Louisiana dance event, it simply makes much better sense. If "fais do-do" derived from a dance step/call, as I suggest, to "faire do-do" would have simply meant to "go dancing," and probably even conjured the image of the back to back dance that the name derives from.

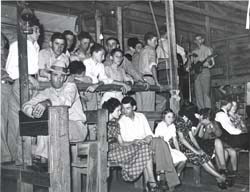

There remains much to be said about this topic, and certainly both etymologies could have overlapped. The striking disparity between the two meanings of "fais do-do" may have struck adults as amusing and even convenient. When lulling a little one to sleep before a night out dancing, when asked where they were going and what they would be doing, perhaps "fais do-do" was the perfect answer: an honest consolation to a sleepy child and a code word for the festivities about to ensue. At the very least, we should consider that there is more to the story than babies dozing in the dim lamplight of rural dance halls.

Sources

Anon. Western Square Dancing - DOSADO.COM. The Premier Internet Portal to Western Square Dance Clubs and Square Dance Callers. Square Dance Music. http://www.dosado.com/.

Cruikshank, George. 1817. Dos à dos: accidents in quadrille dancing. A drawing.

Daigle, Brenda. 1972. Acadian Fiddler Dennis McGee and Acadian Dances. Attakapas Gazette 7.

Fiehrer, Thomas. 1991. From Quadrille to Stomp: The Creole Origins of Jazz. Popular Music 10 (1): 21-38.

Gutierrez, Paige. 1996. Review: [untitled]. The Journal of American Folklore 109 (434): 465-468.

Hallowell, Christopher. 2003. People of the Bayou: Cajun Life in Lost America. Gretna: Pelican Publishing Company.

Karlin, Adam. 2009. New Orleans City Guide. 5th ed. Footscray Vic. London: Lonely Planet.

Lindahl, Carl, Maida Owens, and Renée Harvison, ed. 1997. Swapping Stories: Folktales from Louisiana. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi in association with Louisiana Division of the Arts, Baton Rouge.

Mitcham, Howard. 1992. Creole Gumbo and All That Jazz: A New Orleans Seafood Cookbook. Pelican Publishing. Gretna: Pelican Publishing Company.

Szwed, John F., and Morton Marks. 1988. The Afro-American Transformation of European Set Dances and Dance Suites. Dance Research Journal 20 (1): 29-36.