Ritual Traditions of Maria Lopez: From Mexico to Louisiana

By Susan Roach

Introduction

The small north Louisiana town of Bernice in Union Parish, with a 2009 population of 1629, has become home to a small community of families from the rural state of San Luis Potosi in south central Mexico.

Thanks to the efforts of Maria Lopez, this community is able to experience and maintain many of their native traditions. Now a 40-year old wife and mother of three children, Maria Lopez had left her small village of Villa Juarez, Mexico, with her young son to join her husband in the mid-1990s. When she arrived, she found no familiar rituals from her country; consequently, she slowly began to produce some on her own by drawing on her specialized knowledge she had gained from her experiences. Along with being a full-time cook at Sonic fast food drive in, she produces and directs traditional sacred rituals and creates the crafts and food that decorate and celebrate these events native to her home country.

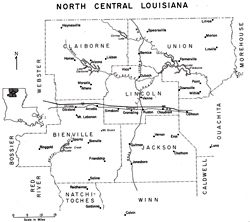

Regarded by her community as an organizing force that brings that community together for sacred occasions, Lopez works closely with other Mexican families in her neighborhood and the nearest Catholic churches Our Lady of Perpetual Help, located in Farmerville, about 15 miles away and St. Thomas Aquinas Catholic Church in Ruston, about 25 miles away. Her documented traditions include rituals such as home altars for saints, the Easter Passion of Christ/ Stations of the Cross Passion play, and quinceañeras; paper and needle crafts (crochet, piñatas, etc.), church and party decorations, and handmade clothing; sacred music; and foodways.1

Interviews with Maria Lopez and the observation of her multiple genres of private and public rituals and their associated crafts and foodways reveal that she had acquired this knowledge of tradition through informal observation and imitation of others in her family and community who practiced these traditions. In other words, she acquired what could be termed "lay knowledge" in the folk tradition. The research reveals the complexity of her lay knowledge and her strong sense of identity and heritage.

While we cannot examine Maria Lopez's whole corpus of knowledge here, we can explore some of her rituals connected to her Catholic belief system, the rituals of Mexican folk Catholicism, related secular rituals, and crafts associated with these rituals.2 These rituals and their crafts include home altars, the enactment of the Passion of Christ (the last hours of life) and rites of passage masses such as quinceañeras and the celebrations (fiestas) following these masses. We can also explore how she learned to perform and modify these rituals to fit her new community, and how she represents and transmits them to her family, community, and the public.

Learning Traditions from the "Organizers" and Other Ritual Specialists

Certainly, not everyone has the knowledge or competence to be able to perform as a ritual specialist who is recognized throughout a community. This deep knowledge, typically, is acquired by only a few people who have an innate interest in learning this type of knowledge. Acknowledged by her community for her artistic abilities in crafting, cooking, and singing as well as organizing large-scale productions, Lopez is an active bearer of these ritual traditions. Knowledgeable community members had identified Lopez as the "main organizer" of events in the Mexican community in Union Parish and facilitated our initial interview with her.

In explaining how she acquired her deep knowledge of ritual, Maria Lopez began by recounting her childhood experience in Villa Juarez. She recalled that in the town where she lived, each year three women were appointed to serve as organizers for the church activities, and they changed every year. Lopez always worked with all the different organizers. She explains: "I always liked to do it. When I lived in Mexico, when I was eleven years old, I would always help them do everything. I would always go up there [asking], 'Would you like me to do something, help you in something?' I always like to help and do whatever I could" (Lopez 29 August 2010). Thus while she was helping, she watched and internalized all she saw and heard, filing it away for future use. One year, her mother was one of the three organizers, so young Maria helped her out using her prior knowledge learned from the other organizers. When others in the community admired her work and asked for her help with their own events, she volunteered eagerly, thus gaining even more experience.

Using and Sharing Lay Knowledge of Hispanic Traditions

By the time she was married at age 21, Maria Lopez's expertise in her village was established. Even after she moved to her husband's village, often she was called back to her home village to organize events. She recalls on one occasion just one month after she had given birth to her first child, people from her village came to get her to help with her cousin's quinceañera. Her cousin bargained for her help: "I'll take care of the baby for you, but you have to help with my quinceañera, also to do their hair and everything" (Lopez 29 August 2010). This example makes it evident that even during her youth, her growing lay knowledge was highly valued in her community and family.

Upon coming to Louisiana a few years later, she brought a rich understanding of her Mexican regional traditions. During her first years in Bernice, the number of families was too small for larger celebrations and rituals. She reports that in those years, the community celebrated the birth of Jesus in La Natividad on December 24 and December 25 at midnight when Christ's birth was celebrated, and a piñata was provided. As the years passed and the community grew, she helped organize additional ritual celebrations. Her 15-year-old daughter Juanita explains:

When she got here, she was one of the first ones to get here and bring in Hispanic [traditions], and she started doing all the Hispanic traditions that she had seen in Mexico, so she brought them here, and then they started doing them, and they all came to my mom saying, "You know how to do more, so I want you to help us to do them." So everybody just comes to my mom, and she will help them (29 August 2010).

In addition to sharing her knowledge with her family and immediate community, she has shared her traditions with schools and festivals. For example, teachers in local schools have asked her to demonstrate piñata making. Also in 2009 at the Natchitoches Folk Festival, she and her friend and neighbor Teresa Turrubiartes were programmed as a team to demonstrate piñata making, crochet, and gorditas (a thick corn cake filled with meat). Their children went to assist with translation. The next year Maria Lopez and her family happily participated again. When asked why she continues to share her knowledge and help with rituals, she responds, "With all the people that come to me, I could just not say no to them. . . . . It's just something that comes into me, inside me, telling me, "You can do it; you can help them out; so just do whatever you can" (Lopez 29 August 2010). She gladly shares a repertoire that ranges from private sacred celebrations to public sacred and secular rituals. Lopez's crafts associated with the various rituals she organizes draw on her knowledge of and materials left from past events. When planning her decorations, Lopez may incorporate leftover craft materials and recycle artificial flowers from previous celebrations to cut down on the expense. Sometimes she may be reimbursed for her expenditures or paid a small fee for handmade items. These crafts range from elaborate handmade dresses for special occasions and quickly made costumes to decorative assemblages used as centerpieces and party favors to crocheted doilies and crocheted covers for various objects. She designs and makes piñatas and other decorations for community birthday parties, baptisms and presentacions and quinceañeras, including decorations for the mass and the table centerpieces made with tiny plastic dolls, lace, and Styrofoam bowls for the fiesta following the mass.

For example, for one quinceañera mass in Farmerville held for twin sisters on June 15, 2007, Mrs. Lopez was in charge of planning, preparing, and installing the decorations. With the help of three friends, and some of their children, she decorated the Our Lady of Perpetual Help Catholic Church the day before the mass. Inspired by quinceañera decorations she had seen on a recent trip to Mexico, Lopez handmade her own unique garlands. To carry out the twin's white and blue color scheme, she hand cut white paper flowers which she strung together with thread encased with blue straws. She attached the garlands to the center of the ceiling and sides of the church with tape to create three arches. The same strings of flowers were draped in a continuous chain on the sides of the last one-fourth of the pews. At one point the garland string broke and had to be repaired, but Lopez quickly improvised a solution, illustrating her ease in coping with issues. When the last garland was too short to reach all the back pews, Lopez was prepared with extra paper-cut flowers, string, and straws to lengthen it. The children helped by taping small bouquets of blue and white artificial flowers at the top of the pews. Lace panels centered with blue and white bouquets of flowers, her last decorative touch, were hung on the front wall behind the altar.

For many of these events Lopez and her husband make some of the food, such as gorditas and barbecue, which is cooked in the traditional outdoor pit. For the party following this quinceañera mass, Lopez's husband spent the whole night before the event cooking the barbecue. Considered a good cook in the community, Lopez herself frequently provides food for ritual events. For more information on the Martinez quinceañera, see XV Años Celebration.