Mardi Gras and the Media: Who's Fooling Whom?

By Barry Jean Ancelet

Journalists routinely travel far and wide to report on what's happening in the country and the world. Their human interest pieces are all the information most of the public has on other people and their culture. Yet reporters often lack the kind of ethnological background to understand the cultures they encounter. Consequently, they frequently produce interpretations considered inaccurate by concerned folklorists and community members, interpretations which misinform their viewers, listeners and readers. This paper examines popular media coverage of the south Louisiana prairie Mardi Gras celebration arid some of its unusual (and erroneous) interpretations as a case study of intercultural misunderstanding.

Though issued from the same liturgical tradition as its counterparts in New Orleans, Rio de Janeiro, and Nice, the Cajun Mardi Gras differs substantially from them. Rooted in the medieval European fête de la quêmande, the course de Mardi Gras is related to other ceremonial begging traditions like Christmas caroling and trick-or-treating in which a procession of revelers travels through the countryside bringing their performance, with them to various homes and requesting a gift in exchange (Ancelet 1980; Lindahl 1984; Spitzer 1987; Ancelet 1987). The Mardi Gras riders seek ingredients for a communal gumbo served at the end of the day. The most interesting gift is a live chicken which the riders catch themselves despite their costumes and varying states of inebriation. They sing and dance, display their masks and costumes, and play roles ranging from the clown to the outlaw, all activities fueled by the ritualized consumption of alcohol. At the end of the day they return to town to eat the fruits of their labor and to dance in a masked ball which ends the festive period and ushers in Lent, traditionally a season of fasting and sacrifice.

Some celebrations retain surprising primitive and medieval survivals. In Kinder and Iota, for example, participants pretend to whip each other with rolled burlap sacks while walking through the countryside. In earlier years, because concealing identities behind masks conferred impunity on the riders Mardi Gras often became a day of reckoning, so often that in the 1940s the celebration was suspended. It was revived in Mamou in the 1950s with strict rules which gave absolute authority to a capitaine and his assistants in order to contain the ritual chaos. The controls established by Paul Tate and Revon Reed in Mamou have served as a model for numerous communities throughout south Louisiana which have revived their own versions of the Mardi Gras. In Mamou and Church Point, the oldest and largest of the revivals, there may be as many as 200 to 300 masked and costumed horsemen who charge farmhouses at full gallop when the Capitaine waves a white flag to signal that a family has agreed to receive their visit.

For the outsider the Cajun Mardi Gras is exotic, colorful and picturesque. Because of its obvious "quaintness," the Cajun Mardi Gras attracts many journalists and documentary filmmakers looking for local color stories (e.g. Blank 1972; Blank 1973; Brunot 1974; Goldsmith 1975; McCallum 1980; Audet 1982; Spitzer and Duplantier 1984). Unfortunately many who visit the Mardi Gras are simply fascinated with the strangeness of it all. They often do not seek out background information to help understand and subsequently explain the underlying complexities. Even if they do, they usually are so blinded by the surface glare that they forget whatever they learned by the time they get back to their word processors or editing rooms. Consequently they usually portray the Mardi Gras only as a surreal procession of masked drunks falling all over themselves, chasing chickens, and sometimes maiming the chickens and themselves in the process.

Media coverage of cultural events is already difficult because of time limits and deadlines (Fishman 1980:34-37). Reporters invariably need to describe the historical and cultural background of an event in a line or two. Journalists readily agree that the combination of deadlines and target audience levels don't allow for the preservation of nuances and complexities, especially in the area called "soft news" (71-72). Reporters often cut off interviews with statements like "That's enough, really. Nobody's going to understand all the details" and "We can only cover the broad strokes." An NBC camera operator working on a story on two 1986 National Heritage Award recipients paraphrased the standard line from network headquarters: "Not too much of that stuff. We don't want to put the audience off. We just need enough offbeat to syncopate the real news. A little bit of that goes a long way, you know." It is difficult to avoid stereotypes and oversimplification in any folklife coverage, and Mardi Gras, which is designed to invert reality and mock the observer, only compounds the problem.

In 1978, when the New Orleans Mardi Gras was threatened by a police strike, ABC sent a 20/20 crew to cover the story and the producer discovered an interesting twist in the fact that the prairie Cajun Mardi Gras was unaffected by the New Orleans strike. This eventually developed into a story which was given the catchy title, "The Mardi Gras They Couldn't Stop" (Brim 1978). The producer met with local sources during her initial research trip to get some background on the celebration. She also described the "story" as they saw it from New York. I met with her at length to explain the cultural and historical significance of the Mardi Gras and the place of the Cajun course du Mardi Gras in the larger scheme of things. After several days, I was confident that I had succeeded in getting her to reconsider this cultural event on its own terms without hauling in preconceived notions from New York. But. by the time the correspondent and crew flew in later, the producer had tossed aside most of what she had learned and at once became the leader of a journalistic safari into Cajun country.

On Sunday the crew went to Church Point to film that town's version of the Mardi Gras and predictably incurred the wrath and ridicule of the riders by getting in the way of the procession and asking obvious questions. At one point, having arrived late at the house with the longest driveway and consequently the most dramatic charge, they even requested that the Capitaine redo the charge, not only disrupting the natural course of the day but also breaking a rule of broadcast journalism not to stage events. At the same time the crew apparently found it difficult to throttle back on their usual hard news approach and misapplied investigative journalism on an unsuspecting cultural event. Much of the piece centered on the heavy use of alcohol during this rite of passage. Instead of telling the cultural story of the Mardi Gras, the piece became a sort of Mardi Gras-gate story which focused primarily on the bizarre distortion of reality created by the juxtaposition of masks and alcohol with real people and examined the country Mardi Gras as a durable (read obstinate) counterpart to the New Orleans party in jeopardy.

Even the most respected journalists are not immune from coming in with a ready-made story. In 1977 two separate NPR crews came to the Mamou area to cover the Mardi Gras. One worked with folklorist Nick Spitzer to cover the black Creole run around Duralde for Folk Festivals, USA. The other covered the Mamou run for All Things Considered. With enough time to develop the kinds of subtleties that the folklorist provided, the first report was satisfying in depth and accuracy. The second crew, on the other hand, "seemed to be looking for sound bites to illustrate a story they had basically developed by the time they arrived, based on the usual expectations of wildness and the laisser le bon temps rouler phenomenon. Basically they had a two or three minute package in mind and spent the whole day listening to the celebration through their earphones" (Spitzer 1985).

Moreover, the All Things Considered crew apparently forgot that they were trying to work during play, which often puts journalists at odds with Mardi Gras participants. A female member of the second crew was especially riled by the macho nature of the Mamou celebration when at one point a band of masked horsemen surrounded her and forced her off the road. Spitzer later noted that she failed to consider that she was, first, a woman in a men's ritual and, second, an outsider asking probing questions during an insiders' ritual. The riders couldn't all articulate a response in her terms, so some had used their horses to communicate their feelings (Spitzer 1985).

A recurring problem among journalists covering the Mardi Gras is that they often don't seem to understand that they are being put on, in the very spirit of the day when they ask questions of the participants whose role for the day, they seem to forget, is to play the fool. In 1975 a crew called TVTV using experimental portable videotape cameras covered the Mamou Mardi Gras for a documentary called "The Good Times Are Killing Me" (Goldsmith et al. 1975). At one point the TVTV crew asked a group of children who were waiting for the Mardi Gras riders' return to town, "What kinds of things do you eat around here?" It is important to understand that Cajuns have parried scrutiny with irony and humor for generations. Practical joking is an integral part of their culture and they will go miles out of their way to put each other on (Ancelet 1984a:107; Ancelet 1984b: 182-186). And outsiders fare no better (or worse), whether they understand it or not. Armed with a question about what they eat on any day of the year, many self-respecting Cajun kids would have jumped at the opportunity to play with its asker. Remember too that this is Mardi Gras day, on which playing the fool is not only acceptable but expected. True to their cultural heritage and to the spirit of the day, those children in Basile spouted off a litany of foods that they felt would be bizarre and disgusting to outsiders, including squirrel heads, crawfish, and frogs.

The children on the streets of Basile succeeded in "fooling" the documentary crew. The only problem was that the crew apparently didn't know that they had been "fooled" because they treated this information in their videotape as an anthropological discovery which reinforced their own stereotypes of the Cajuns. The TVTV crew used this information because the media generally perceives that people are interested in how other people are different. Even if they had recorded balancing statements that Cajuns also eat fried chicken and hamburgers, these remarks would likely have ended up on the cutting room floor because how people are the same is not as interesting. But what about the family in Nebraska watching PBS one night and hearing this list of foods with which they are unfamiliar and which they may consider to be grotesque? Did they know that there is "ordinary stuff that was not used because it didn't illustrate the difference between Cajuns and themselves? Did they understand that it was Mardi Gras? Did they understand that Cajuns like to kid each other, and others? Or were they too in turn fooled? And what about the children at the Mardi Gras? They first succeeded in fooling the crew, but were they then fooled when the program aired creating second generation misinterpretations? And who is ultimately responsible for fooling the family in Nebraska? Should the children or other participants be expected to understand these issues, or should it be the journalists whose profession it is to analyze and interpret the facts?

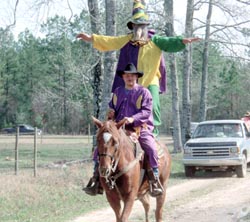

Consider a similar example. In a 1985 article, Time blue highways-style reporter Gregory Jaynes quotes a Mamou Mardi Gras participant as saying, "See that boy dancing on that horse. . . . I never thought he'd be up this morning. Last night he was arrested for parking his horse in the wrong place. He thought he tied it to a parking meter but it was a fire hydrant" (14-15). The reader is not told that dancing on horseback is a common ritual exhibition of skill and machismo among Cajun cowboys during Mardi Gras. The jest about the horse tied to a fire hydrant Jaynes lets fend for itself. Without background information the whole incident comes across as bi-zarre, at best.

After taking a pot shot at the Cajuns' native language ("Cajun French has about as much in common with the French language as a claw hammer has with poetry"), Jaynes quotes another Mardi Gras rider for a "typical" example of Cajun English: "I told him for a job, he ask me no" (15), again assuming that the people he was interviewing were playing it straight when in fact that was exactly the opposite of their intention. They meant to fool him. But, again, who fooled whom? After reading Jayne's column, a woman from Flat Bush, New Jersey, wrote to the editor of Time that she was certainly happy that she didn't live in the Mamou that was described. The reaction to her comment among the folks in Mamou was generally that they were happy too that she did not live there if she couldn't even take a joke. In their minds the joke was on Jaynes and the lady from New Jersey. Among people across the rest of the country who took Jayne's piece at face value, however, it seems clear that the joke was on Mamou. The remaining question is, where do reporters like Jaynes fit between Mamou and Flat Bush?

Even when journalists are in the spirit of things and understand the play involved, they sometimes don't successfully pass that information along to the audience, for whatever reason. For a definition of the Mardi Gras the TVTV crew asked a slightly drunk teenaged participant who offered, "Get drunk and have fun and dance. Get chickens. "That's the meaning of Mardi Gras." (Goldsmith et al. 1975) Now it is certainly not reproachable to ask for the participant's point of view. However, at no time during the documentary did they balance the scales by interviewing Mardi Gras reviver and former Capitaine Paul Tate or current Capitaine Jasper Manual or any other informed source. Nor was the young Mardi Gras rider wrong. He could not be expected to wax eloquent on the deep meaning of the Mardi Gras from his point of view as a young initiate in the tradition.

Similarly, Jaynes offered the following assessment of what he learned in Mamou: "The lesson seemed to be: get drunk, hunt chickens, eat well, kiss the dickens out of pretty girls, straighten your deportment the next day, assume your place among your fellow men" (1985:15), this despite talking to Mardi Gras organizer Paul Tate, Jr., who filled him in on the history and development of the tradition during a three-hour session at the Traveler's Cafe on Monday before Mardi Gras. Jaynes apparently passed little of this information on in his report. Tate, who unsuccessfully sued the Washington Post and reporter John Ed Bradley for allegedly misrepresenting him in a similar piece (Bradley 1984), thinks Jaynes was "distracted by other issues which shocked his East Coast liberal sensibilities, like the machismo of it all" (Tate 1985). Indeed he described the fights in much more detail than the costumes or the chicken chase. He seemed particularly preoccupied with the rule excluding women. According to Tate, Jaynes was upset because his girlfriend was not allowed to participate. Tate gave him several reasons including the fact that the women in Mamou were the ones who imposed and enforced the rule. All Jaynes used from that lengthy interview was a joke about the role of women that Tate flipped off as they were adjourning to Fred's Lounge (Tate 1985). In effect, Jaynes used his position at the typewriter to ridicule the culture's internal operatives, having failed to impose his own from the outside. He did not, however, reject the celebration wholesale. By his own admission, the alcohol he drank stained and strained his memory (1985:14).

In one of its early sequences, just after giving a general introduction to Cajun culture, "The Good Times Are Killing Me" presents Louis Landreneau, a young man whose mother is helping him dress as a female nurse, a costume appropriate to the traditional Mardi Gras role reversal (rich and poor, male and female, etc.). Unfortunately the film has not introduced the Mardi Gras yet. The celebration has been cryptically suggested by extreme wide-angle close-ups of a chicken with the Mardi Gras song as a sound-over. Consequently the sequence seems to represent a transvestite being dressed by his mother who calls him Louise. That impression is enhanced for the informal viewer by lines spoken in jest like "My mother always wanted a girl" and "I don't have a girlfriend right now," lines which any trained observer would recognize as Mardi Gras play. It is not until much later, when the Mardi Gras is formally introduced, that the viewer is given a clue that this might be part of a ritual. I wonder if the casual viewer can be expected to make such sophisticated deductions. The motives of the film crew must also be questioned here, especially since Mr. Landreneau protested specifically that he did not want the crew to use footage of him dressing because he feared that people would get the wrong idea (Landreneau 1975).

At another point in their film, this same TVTV crew betrayed its bias with a remarkable question and answer sequence. While following the Mardi Gras riders through the countryside, they happened on a farmer dressed in starched khakis watching the procession while standing by the side of the road in front of his house. Someone off camera asked, "What do you think about this?" leading to the following exchange:

"I've never run Mardi Gras before and if nothing happens, I'll never run."

"Why's that?"

"I don't like that. I'm glad for the ones that like it though. But me . . ."

"Why don't you like it?"

"Because, I don't like to jump around all day like that. Then a fellow's got to drink if he wants to run Mardi Gras and it gets him sick the next day."

"Are you a Cajun?"

"Yeah, that's what I am."

"You don't sound like a Cajun."

"Why?"

"Most Cajuns like to run around and have a . . ,"

"Yeah, most of them like to, but not me." (Goldsmith et al. 1975)

The TVTV crew seemed genuinely shocked to find someone who didn't fit their notion of what a Cajun should be. The very next scene put things back into (their) perspective with drunk riders slurring the meaning of Mardi Gras.

Finally, the camera and tape recorder themselves are frequently overlooked factors in the relationship between the documenter and the documented. Pointing a lens or a microphone at people often make ordinary folks act and speak in a self-conscious way. Some people feel uncomfortable in front of a camera and clam up. Others ham it up, overreacting for the record. These factors must be taken into account by the serious documenter when editing footage into a final story. TVTV, whose credits also include a special illustrating former President Gerald Ford's supposed clumsiness, may have misapplied their warts-and-all style of journalistic reporting to the documentation of a cultural event. Moreover, pointing a camera at a Mardi Gras rider whose goal is to play is all the cue he needs. This can lead to some very interesting performances, but it should be remembered that they are performances and not to be confused with reality.

An important part of the function of the Mardi Gras, of course, is to turn reality on its ear, making it difficult if not downright impossible to get a clear look at the host culture during this traditional festival. Yet journalists and filmmakers interested in documenting the Cajuns often schedule their visits to south Louisiana so that they will be able to cover the Mardi Gras as part of their research. In the worst cases these are on-the-road journalists who are primarily interested in grist for their "rube story" mills (Edmunds 1985). Even in the best of cases, however, many observers frequently come away with a distorted understanding of the culture in general because they forget to consider that they viewed it through a lens which is designed to distort. Often they base their reports on fascination rather than understanding. Sometimes they are even drawn into the festivities they are trying to observe and have to sift through beer-stained mental notes for information later. They rarely understand enough about the culture to know when they are being kidded and thus indiscriminately record stories meant to amuse. Unfortunately many go on to analyze the Mardi Gras only in terms of this misinformation and apparent foolishness. Those who expand this shaky analysis to use the Mardi Gras as a metaphor for the whole society confuse play with ordinary life and confuse their audiences as well in the bargain. Sadly this approach creates intercultural misunderstanding rather than the understanding we hope for as concerned folklorists.

Sources

Ancelet, Barry Jean. 1980. The Country Mardi Gras Celebration. Attakapas Gazette 15:159-164.

_____. 1984a. The Makers of Cajun Music. Austin: University of Texas Press.

_____. 1984b. La Truie dans la berouette: Etude de la tradition orale en Louisiana Francophone. Doctorat du 3e cycle dissertation. Etudes Creoles, Universite d'Aix Marseille I.

_____. 1987. Mardi Gras. in The Cajuns: Their History and Culture, report lo the Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and the National Park Service 2:87-101.

Audet, Robert. 1982. Mardi Gras Louisiana. Film, 53 min. Cinequip Production. Blank, Les. 1972. Dry Wood. Film, 37 min. Flower Films.

_____. 1973. Spend It All. Film, 41 min. Flower Films.

Bradley, John Ed. 1984, Cajun Mardi Gras: The Native Returns For Raucous Riles. Washington Post 17 March.

Brim, Peggy, producer. 1978. The Mardi Gras They Couldn't Stop. Report on 20/20 News Magazine, ABC Television.

Brunot, Jean-Pierre. 1973. Dedans le sud de la Louisiane. Film, 43 min. Bayou Films.

Edmunds, James. 1986. Personal interview.

Fishman, Mark. 1980. Manufacturing the News. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Goldsmith, Paul et al. 1975. The Good Times Are Killing Me. Videotape, 58 mm. TVTV.

Jaynes, Gregory. 1985. Louisiana: A Mad, Mad Mardi Gras. in American Scene. Time 125:14-15.

Landreneau, Louis. 1975. Personal interview.

Lindahl, Carl. 1984. Bahktin and the Nature of Carnival Laughter. Unpublished typescript.

McCalium, Michael et al. 1980. Soileau Mardi Gras. Videotape, 15 min. Crossover Productions.

Spitzer. Nicholas. 1985. Personal interview.

_____. Zydeco and Mardi Gras. Report to the Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and the National Park Service.

Spitzer, Nicholas and Stephen Duplantier. 1984. Zydeco. Film, 58 min. Bayou Films. Tate, Paul, Jr. 1987. Personal interview.