The African American Toast Tradition

By Mona Lisa Saloy

As evidenced in print and music, African Americans boast a lively verbal art tradition that includes tales, toasts, and adventures of bad guys who confront and vanquish any adversary instantly and guiltlessly. From Reconstruction to the jazz age through today, this boasting tradition has been a uniquely urban phenomenon.

"Toasts" are performed narratives of often urban but always heroic events. For many Blacks, both performers and audience, hearing about or performing the winning ways of the central character becomes as creative a release as Black music. Toasting is today's continuance of an oral tradition, but many contemporary toasters read their complicated and elaborate versions from a text. As with any oral tradition, many versions of the same toast exist. The toast is a dynamic performance within the Black community of recognizable and popular central characters. They are performed in bars, libraries, community centers, and even college campuses. However, less explicit toasts are performed by anyone at any time for entertainment.

A toast well known in any large American city with a significant Black population is "Shine and the Titanic." This toast relates the heroic efforts of an old Black stoker to warn of the ship's impending disaster, but when ignored, he strives to save himself. The Titanic sank on its maiden voyage in 1912, during the Jim Crow days when Blacks were not allowed as passengers.

Toasts are typical of other Black traditions, such as quilting and gospel, in that improvisation is highly valued. Therefore, one will find many different versions of any toast; many use profane street speech. This version of "Shine and the Titanic" heard by the author in Oakland, California, has been edited for publication.

In toasts, historical accuracy is not considered important. For instance, although in reality the Titanic sank in April, in the ballad it sinks in May. Audiences expect, accept, and appreciate the toaster's improvisations.

As is common in toasts, a narrator describes Shines's successful exploits, while Shine directly addresses the captain, his daughter, and the whale. Shine, the black stoker and hero of the toast, repeatedly warns the white captain of the impending disaster and humbly gives updates on the sinking ship. Even though Shine is ignored, hustled, and chased by a whale, he remains confident of his ability and determination. It is Shine alone who can save the day.

Shine and the Titanic

It was a hell of a day in the merry month of May

When the great Titanic was sailing away.

The captain and his daughter was there, too,

And old black Shine, he didn't need no crew.

Shine was downstairs eating his peas

When the . . .water come up to his knees.

He said, "Captain, Captain, I was downstairs eating my peas When the water come up to my knees."

He said, "Shine, Shine, set your black self down.

I got ninety-nine pumps to pump the water down."

Shine went downstairs looking through space.

That's when the water came up to his waist.

He said, "Captain, Captain, I was downstairs looking through space,

That's when the water came up to my waist."

He said, "Shine, Shine, set your black self down.

I got ninety-nine pumps to pump the water down."

Shine went downstairs, he ate a piece of bread.

That's when the water came above his head.

He said, "Captain, Captain, I was downstairs eating my bread

And the . . .water came above my head."

He said, "Shine, Shine, set your black self down.

I got ninety-nine pumps to pump the water down."

Shine took off his shirt, took a dive. He took one stroke

And the water pushed him like it pushed a motorboat.

I'll give you more money than any black man see."

Shine said, "Money is good on land or sea.

Take off your shirt and swim like me."

And Shine Swam on.

Shine met up with the whale.

The whale said, "Shine, Shine, you swim mighty fine,

But if you miss one stroke, your black self is mine."

Shine said, "You may be the king of the ocean, king of the sea,

But you got to be a swimming son-of-a-gun to out-swim me."

And Shine swam on.

Now when the news got to the port, the great Titanic has sunk,

You won't believe this, but old Shine was on the corner damn near drunk.

As popular a toast as "Shine and the Titanic," "The Signifying Monkey" is an animal tale that occurs in many versions. The following is a child's version of this popular toast.

The Signifying Monkey

The Monkey and the Lion

Got to talking one day.

Monkey looked down and said, Lion,

I hear you's a king in every way.

But I know somebody

Who do not think that is true--

He told me he could whip

The living daylights out of you.

A New Orleans toaster, Christopher Wilkinson, defines the toast as a mostly male event. Wilkinson is aware that some women and men are often offended by versions including profanity, negative views of Black women, or sexual explicitness. However, he feels that most men find a release and celebration in the heroic deeds of the central character in the toast. The toaster relates to Shine's fantastic heroic feats. In the case of the Signifying Monkey, a continuously grueling verbal duel is in process with the little but clever Monkey instigating, taking knocks but getting up like a champ. Blacks celebrate the uplift the accomplishments bring, however fanciful. He/Shine was the hero; the Black man wins for a change. In a society imposing siege upon Black men (there are more Black men in prison than in college), toasting becomes a creative and liberating experience. In toasts, a Black does the "top talking" and the winning. As a result, the toast tradition has survived as a folk event because it provide s cultural identification and reinforcement for participants.

For this year's festival two New Orleans toasters will be presented: Arthur Pfister and Christopher Wilkinson. Christopher Wilkinson, born in New Orleans but raised in Bunkie, is a toaster in the more traditional sense. His training was strictly verbal from another toaster. Wilkinson learned some toasts by heart and presents them with a lot of heart. He performs "Dolomite", "Shine," and a version of the "Signifying Monkey." As a family man and sanitation worker in New Orleans, Wilkinson's performances are usually for family, friends, and associates. They tend to be male, since as he says most women, especially in Catholic/Baptist New Orleans, are often offended. Christopher Wilkinson will deliver a lively and entertaining, but self-censured, performance.

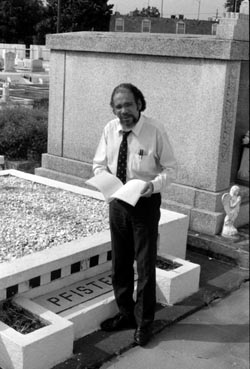

On the other hand, Arthur Pfister is a working professional who teaches English for the Urban League in New Orleans. Pfister performs his own New Orleans version of "Shine and the Titanic," and he composes his own toasts such as "The Ballad of Billy Bob" and its X-rated counterpart "The Ballad of Nigger Bob." Pfister is also a poet and fiction writer born in New Orleans at Charity Hospital, he adds. He is the author of a published volume of poetry, Beer Cans, Bullets, Things, and Pieces with an introduction by Amiri Baraka. He is an editor, speech writer, graphic designer, and professor who received a Master of Arts in Writing from John Hopkins University and a Bachelor of Arts degree in Journalism from the State University of New York. Pfister is also a former Writer-in-Residence at Texas Southern University. His works have appeared in Farhari ("pride" in Kiswahili), The American Poetry Review, The Minnesota Review, and others. He received a Discovery Grant from the National Endowment of the Arts, and he served as visiting poet at Northeastern University's Afro American Studies Center.

An unusual quality of Pfister's is his appeal to audiences with any lecture, speech, poem, or toast. Arthur Pfister is a well-known performer on radio, television, at community centers, libraries, and cultural events. His is an ongoing contribution to African American oral and literary traditions.

Both Wilkinson and Pfister regard themselves as tradition-bearers, and their communities revere them as toasters as well. They enjoy performing toasts, and intend to keep this tradition alive.

To date, important research on versions of Shine and the toast tradition is available (Jackson 1974, Abrahams 1970). But additional research is needed to answer questions about this oral tradition. Some questions for this year's audience to consider are: How widespread a tradition is toasting in Louisiana? Does toasting occur in rural areas in this state? Are toasters found outside New Orleans in smaller cities? Are there women toasters? Do these toasters predict a change in the toast tradition? If so, what changes should we expect? Will media ever replace the need to toast?

Perhaps, this year's presentation

of the toast tradition in Louisiana will not only document the

occurrence of this continuing dynamic tradition, but may attempt

to address these issues.

Sources

Abrahams, Roger D. 1964. Deep Down in the Jungle, Negro Narrative Folklore from the Streets of Philadelphia. Hatboro, Pennsylvania.

Abrahams, Roger D. 1970. Positively Black. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Jackson, Bruce. 1974. Get Your Ass in the Water and Swim Like Me. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Levine, Lawrence W. 1978. Black Culture and Black Consciousness, Afro-American Folk Thought From Slavery To Freedom. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Saxon, Lyle, Edward Dreyer, and Robert Tallant editors. 1988. Gumbo Ya Ya, a

Collection of Louisiana Folktales. Gretna: Pelican Publishing Company. (originally published in 1938.)

Shine and the Titanic, The Signifying Monkey, Stackolee, and Other Stories from Down Home. San Francisco: The More Publishing Company, 1970.