Keep Your Mind and Your Hands Busy: Expressive Dimensions of the Lone Quilter

By Susan Roach

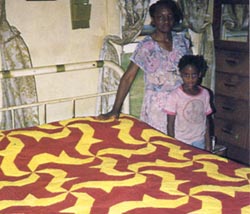

Traditional quilters have often been stereotypically depicted as producing quilts communally in quilting bees. Although urban senior citizens' centers, church groups, and homemaker clubs sometimes organize group quilting especially for fund-raising or festivals, for the most part the quilts made in rural North Louisiana today are pieced and quilted by women working alone. I studied a number of "lone" quilters in Louisiana from 1979 to 1985, and my sample of over thirty such white, Protestant women, aged fifty-three to ninety-three, who learned quilting in a traditional family context in rural North Louisiana, provides data on the development of their quilting skills and the place of this folk art through their lives.

All these women grew up in the North Louisiana hill country region in the north central and western parishes of the state and remained close to their birthplaces. This upland hill country of North Louisiana was settled mainly by Scotch-Irish descendants, primarily Baptists and Methodists, in the mid to late 1800s. These highly religious Protestants, like other Calvinists, believed in self-reliance, hard work, thrift, and improving one's condition in life (Leyburn 1962:322). Today the area still strongly adheres to its roots in evangelical fundamentalist Protestantism, which, no doubt, keeps the area conservative and slow to change. One informant, Doris Nolen from Vernon Parish, expressed her consciousness of how this conservatism originated in her own behavior: "It was in the family; we just do traditional things. We are country hill people, and we just more or less do things the older ways."

Mainly, these rural people were historically self-sufficient farmers. Although today rural citizens are, of course, mainstream consumers, they still grow a large part of their own food and continue traditional food preservation. Given the hard labor required by subsistence farming, their Protestant work ethic, and the difficult economic times of these women who lived through the Depression, it is not surprising that they were not strangers to hard work. Imprinting this work model even more indelibly on their minds was the fact that their mothers were role models for seasonal action, typified in the following description:

Mama always believed in keeping somebody busy and she kept busy herself. You had gardening in the spring and canning in the summer, and in wintertime you quilted and pieced scraps, and we sewed our garments then sometimes.

Often both women and children helped out in the field. In most cases, however, especially for women who had to provide quilts for their families, quilting was not neglected but had its own season, as Hilda Gentry of Grant Parish explains: "I worked in the fields just like a man in the summer and spring, but when fall and winter came, well, that's when I pieced scraps all the time." Sometimes women also piece at night year round, but most insist, even today in the era of air conditioning, that it is too hot to quilt in the summer.

Today these rural women tend to follow this seasonal regimen until they are no longer physically able to continue their outdoor work or until their husbands no longer farm. Some even past the age of eighty continue to have small vegetable and flower gardens. Generally, as they get older they tend to spend more day time on their quilts. More active younger women such as Opal Madden, who has school-aged children, care for their families and help out with the farm and garden during the day and work on quilts at night and in the few spare moments found during the day.

In addition to these seasonal

and daily rhythms of quilting, there is a larger rhythm of quilting

in the life cycles of these women. This rhythm becomes evident

when the life histories of these women are examined to determine

how quilting expertise is developed and used through their lives.

The general pattern of quilting experience among this group can

be divided roughly into four stages, which, interestingly, parallel

the four developmental phases of the old-time fiddlers' lives

discussed by Jabbour (1982:144). Jabbour found that the artistic

development of old-time fiddlers began with the fiddlers' learning

to play from ages seven to fifteen in the first stage, learning

the finer points of the art from fifteen to thirty in the second

stage, going through a more or less dormant phase in their middle

years when they dealt with work and family responsibilities,

and going back to fiddling with greater intensity from ages fifty-five

to ninety, when their fiddling flourished. Although the ages

of these quilters' development differ slightly from the fiddlers',

a similar rhythm exists. Their first stage of learning quilting

took place as early as four and lasted until about age fifteen.

Learning to make quilts in the context of family was a gradual,

informal process.

Girls began learning by simply stitching pieces of cloth together. Piecing of quilt tops was learned before quilting, beginning with simple "string" or "Nine Patch" patterns. A few women who could not remember not knowing how to quilt may have begun piecing at age four or earlier. As Nova Mercer, of Jackson Parish, jokingly put it: "I was born with a needle and thread in my hand instead of a silver spoon," a statement which refers to a very early knowledge of sewing and also to a life of work instead of leisure. Mittie Weldon, of Union Parish, who does remember learning to piece on a "string" quilt described her experience:

Before I was old enough to go to school, my mother cut out a square of paper, and she'd put in two pieces of cloth on it, and she wrapped a cloth around my middle finger. We wrapped it real tight so my needle wouldn't stick me and that's the way I'd push my needle. Of course, I'd make long stitches going in and out sewing those two pieces together.

Children were not expected to conform to the aesthetic standard of small stitches until they had had much practice. Although many began basic piecing at the age of five or six, they did not quilt on their mothers' frames until several years later. Young girls might play at quilting, taking a few stitches on their mothers' quilts, which would usually be taken out, or as in the case of Lucy McGee, of Rapides Parish, they might make doll quilts. Mrs. McGee remembers making her own small frames to quilt her doll quilts when she was nine. This is somewhat early to begin quilting even in a miniature fashion; however, some girls, of course, were more competent at sewing earlier. Typically, around the age of thirteen, the girls began helping their mothers with the family quilting. In many cases, quilting was put off until this age because the girls had to work in the fields when they were not in school. As in the case of Mittie Weldon:

I guess I have been about thirteen when I first begun to quilt, 'cause we lived on a farm and I worked in the fields with my daddy and my brothers and I wasn't at the house to do any quilting.

Also the height of the quilting frames, adjusted for an adult, as well as the difficulty of the quilting stitch, which demands strength in the hands and arms, may have prohibited much quilting before the age of greater body growth and coordination. During this learning stage, girls learned quilting basics through their family models until they were able to perform well enough to help their mothers provide quilts for cover.

The next stage of the quilter's development began when she was on her own. Usually this stage is marked by marriage; however, in some cases teenagers were forced into a place of responsibility before marriage. Consequently, it is difficult to pinpoint an age when this second phase of development might begin. Also some women married earlier than others, while others who married later might not have been as motivated to develop their skills. For example, Hilda Gentry, at age fourteen, lost her mother, leaving Hilda to care for her father and younger siblings. Hilda had never put in a quilt alone, but she had helped her mother many times; so her determination, along with her experience of watching and helping her mother quilt, enabled her to accomplish the difficult task alone. Because she had to care for a large family, cooking, washing by hand, and working in the fields, she learned at an early age to make quilts that would last. She followed her mother's model of quilting in "shells" about one-half inch apart with coarse "ball thread" regardless of how fancy the pattern or how brilliant the colors. She continued this method of quilting which she notes no one else in the community did exactly like she did. She believed that the extra quilting strengthened the quilt, making it last longer.

Although many women may have approached their marriage with several quilts for their hope chest (often made with family help), just after their marriages the women often made a number of quilts to use in their new homes. Frequently, these were what they termed "fancier" quilts than their mothers had made. Several quilters, on looking back at their early quilting experience with their mothers, see it as teaching them only the basic rudiments of quiltmaking and none of the finer points, such as keeping the quilting stitches small and quilting "fancy" motifs. Both Minnie Lee Graves and Opal Madden of Lincoln Parish, did not admire their early family quilts; Mrs. Graves said that she and her mother did not really quilt; they only "basted," meaning they did not do the tiny stitches on their everyday quilts. Opal Madden did not actually learn very much about quilting in a frame from her mother because they usually tacked their quilts instead of quilting them. However, both Mrs. Graves and Mrs. Madden became interested in what they term"fancy" quilting by watching their rural neighbors quilt. With the help of these new neighbors, the two young married women began to add "fancy" quilting to their repertoire of "everyday" quilting. Often, as in the case of Opal Madden and Eva Colvin, a new family member, such as a mother-in-law, was an encouragement to develop quilt-making skills. Usually, a new baby in the first few years of marriage also called for a fancy "baby quilt" or "crib quilt." With the appearance of children, though, quilting could be slowed down considerably, with the responsibilities of raising a family.

During the next stage of the women's life cycle, which falls during the middle years from approximately age thirty to fifty, depending on the age of marriage and the birthdates of her children, if any, most women made fewer quilts than they had during the previous years. These were usually either supplementary, everyday quilts for cover or gifts marking occasions such as relatives' marriages or births. The older women in this sample who raised large families during the Depression, of course, had to make more quilts. In the case of the younger women interviewed, who were raising their families in the 1950s ad 1960s, fewer quilts were needed, since electric blankets had come into vogue. Opal Madden, however, is an exception to this rule because she has consistently made around one quilt per year since she started quilting again after her marriage. Also, she does not use her quilts except on special occasions when she may put one out on a bed "for show." She does, since her husband prefers them, but she uses old ones her mother-in-law made for this purpose. With one son still in elementary school and farm work to help with, Mrs. Madden cannot spend as much time as she would like on her quilting. By entering her quilts in local and state fairs and being recognized by her Homemaker Club, Opal Madden has become a community celebrity, a fact that probably makes her more involved in her quilting than most women in this middle period. It will be interesting to follow her development after her last child leaves home, through the fourth stage, which in other quilters has been their most prolific.

The last stage of development runs from about age fifty or so onward until physical infirmities prohibit quilt-making. The popular revival of interest in quilting running from the late1960s until the present does coincide with this increase of quilting activity among these particular traditional quilters; however, for most of them, the revival has had little effect on their work other than providing a greater, more appreciative market for their quilts and offering a wider variety of quilt patterns readily accessible in popular magazines. One traditional quilter, Nova Mercer, has been more influenced by this revival than the other quilters, claiming that she had only learned to make "fancy" quilts just a few years ago from books and magazines. She was most proud of the quilts she had copied almost exactly from covers of McCall's Quilting Magazine; yet she claims she prefers to piece the string quilts best. Although her quilts are inspired by popular books, her construction techniques remain highly traditional, the main difference being that she takes more time and care with her fancy quilts than she did with her later quilts, probably because she consciously collects fabric, usually scraps from friends, remnants, and occasionally large pieces from fabric shops. Mrs. Mercer, who took up more quilting during this time of her life because of restricted activity due to reasons of health, sells some of her quilts, but prefers to keep them as heirlooms for her children, a common phenomenon.

The increase of quilting activity among traditional quilters in this phase is, no doubt, stimulated by the family events which traditionally call for a gift such as a quilt. At this time in their lives, the women might have children getting married, then births of grandchildren, and later marriages of these grandchildren-all events which traditionally require a quilt to mark the occasion. Even women who do not quilt themselves often piece tops and pay other women who quilt for the public to quilt them so that they will have a quilt for each of the grandchildren when they get married. Several of the women in my sample have quilted for the public, but of these Minnie Lee Graves and Mittie Weldon have done the most. In their eighties, they quilt fifteen to twenty quilts per year, for a modest price of thirty-five to fifty dollars per quilt, depending on the size of the quilt and the amount of the quilting wanted. Both used the money to supplement their small retirement incomes, and Mrs. Weldon also used part of her money to make larger church contributions. Mrs Artie Lindsey, of Bienville Parish, uses the money she gets from quilting and from selling an occasional quilt to buy gifts for her grown children. Giving away and selling her quilts, she likens herself to the shoemaker's wife and children who had no shoes: "I'm the quilt-maker and I don't have a decent quilt to cover the bed."

Since the income from quilting is so small, it seems unlikely that economics is a prime reason for quilting, especially at the time when the women are growing older and health may be failing. Actually, except for failing eyesight, poor health seems to have little effect on the amount of quilting done by these women. They continue, in spite of arthritis, heart problems, and cancer. Doris Nolen, for example, to ease her angina, quilts standing up at her frame, and eighty-two year old Minnie Lee Graves was away from her frames less than three months after major surgery. Mrs. Graves explains it: "I have to have something to keep busy." Most voice the same feeling about not wanting to "sit and hold my hands." Mrs. Mozelle Durrett, of Lincoln Parish, reaffirms this and gives a reason why: "I always had to have something to keep busy and that [quilting] was a way to keep busy. I think a lot of people would be better off if they did do that." Her maxim harks back to the Protestant ethic with its abhorrence of idleness and its evils, but it also points to a need to stay mentally active. Quilt-making does provide this mental challenge as well as physical activity, which calms the nerves. It allows for the creativity of the bricoleur at a time when their lives may be emptier with children gone, husbands deceased, and social life limited because of health problems (see Lévi Strauss 1969:17 on bricolage). As Artie Lindsey, of Bienville Parish, puts it: "It just fascinates me that you can take those scraps and put them together and make something beautiful. Now that's me. I've created something. . . . I look at what I make quilts of as something that would have been throwed away because they were just old scraps left from clothes or something." Again it may be said that the thriftiness of patchwork agrees with the tenets of the Protestant ethic, but also it is the basic appeal of transvaluation, the magic of turning rubbish into something valuable and worthwhile (Thompson 1979). However, as Mrs. Durrett explains it, only certain types of rubbish are worth transforming and not all resulting objects are of equal value:

I just like to create things, to make something worthwhile. A lot of people take these detergent bottles and cut out and make something; well, really I don't feel like I've done anything such as that [laughing]. What I want to do is something that is worthwhile to show for what I've done, I guess. There's a woman lives here that takes clocks and she takes these egg cartons and she cuts them up and puts them around them. When she gets through, it's big and she uses clothes pins and all-well, I really don't feel like you have much when you done that because it's not something that will last on, and of course, it's showy, maybe, but it's just not my type. I'll say. . . It does show right now, but it's not lasting.

For the traditional quilter, quilting is a type of folk art which is more worthwhile than popular crafts made from more perishable materials that will not last like the quilt will. The popular crafts will probably have the life span of other popular fads, whereas quilts have been made for generations. Unlike the popular fad crafts, quilts will outlast their makers. It offers her a means to continue the lifestyle of work to which she has become accustomed. She carries on her craft throughout the life cycle, aware that it binds her to the past, gets her through the present, and lasts into the future as heirlooms which will go on to color new lives. Just as she worked seasonally in her garden, the quilt-maker works on her quilts during the winter of her life, her art flowering and warming her spirits.

References Cited

Jabbour, Alan. 1982. "Some Thoughts from a Folk Cultural Perspective," In Perspectives on Aging: Exploding the Myths, ed. Priscilla W. Johnston, pp. 140-44. Cambridge, Mass.: Ballinger Publishing Co.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude. 1969. The Savage Mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Leyburn, J. G. 1962. The Scotch-Irish: A Social History. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Thompson, Michael. 1979. Rubbish Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.