PANEL 1

A Better Life for All: Traditional Arts of Louisiana's Immigrant Communities

A Traveling Exhibit from the Louisiana State Museum

In collaboration with the Louisiana Division of the Arts Folklife Program. We regret that the exhibit is no longer available for traveling.

PANEL 2

A Better Life for All: Traditional Arts of Louisiana's Immigrant Communities

For centuries, people have made their way to the Bayou State, known for its hospitable climate, welcoming feeling, and plentiful opportunities. The state map abounds with names like Manila Village and Côte des Allemandes (German Coast), revealing a history and heritage interwoven from many cultures. As new immigrant communities take root, Louisiana blossoms.

Generations of immigrants have come to Louisiana for economic, educational and professional opportunity, political freedom and safety, or even a sense of adventure. Whatever their reasons, most come seeking a better life while bringing an abiding love of their native culture, nourished through traditional practices. Whether part of everyday life or special occasions, time-honored foods, music, dance, crafts, and rituals anchor people in a new home and add to our state's cultural abundance.

PANEL 3

A Taste of Home: Cultural Foodways

A portable form of knowledge, foodways are among the first and most lasting cultural traditions to be established in a new home and maintained by future generations. Ethnic grocery stores and restaurants are often the earliest signs of new cultural communities, as people long for a taste of home and require special ingredients for native dishes. These businesses become community gathering places, and an entry point for others to discover new neighbors. The heart of family and community celebrations, traditional foods bring comfort to daily life. For some, their cultural cuisine may become a source of income or a way to raise money for a community cause.

She who wants to be married must do pita."

-Hasan Stranjac, husband of Emira Stranjac, Baton Rouge

Pita pastry, a hallmark of Bosnian cooking, is among the traditions Emira Stranjac has maintained in her Baton Rouge home since 2000, when her family arrived as war refugees. While pita-making was a prerequisite for marriage in Emira's generation, her daughter learned to make this delicacy simply because she enjoys eating it. The Stranjacs raised their family in the U.S., where their children have better opportunities than in Bosnia. Although Emira sees her daughter as an "American girl," cooking and other cultural traditions keep the family connected to their homeland.

Below: Fresh from the oven: Bosnian pita pastry. Photos: Jon Donlon, 2007

"We always, [in] our culture, use the corn. It's the base for everything."

-Diana Gay, Ruston

Diana Gay's Guatamales embody her journey from Guatemala to her adopted home in Ruston, where she married a Louisiana native in 2000. As a child, she learned the day-long process of tamale-making from her mother, but it wasn't until she lived in the U.S. that Diana made tamales, or chuchitos, regularly. Following in her mother's footsteps, she rises early on Christmas mornings to make 100-200 tamales. Throughout the year, she makes them for her family, for sale to others, and at educational demonstrations.

One of the largest immigrant communities in Louisiana, the Vietnamese began settling in New Orleans soon after the Vietnam War ended in 1975. Tet, the Vietnamese Lunar New Year, is the most important holiday, marking the beginning of spring. In New Orleans, Tet remains a time for family reunions and material and spiritual renewal.

The Legend of Bánh Chung

Three thousand years ago, when King Hung Vuong VI of ancient Vietnam grew old, he gathered his sons, announcing he would bestow his throne to the one who brought him the most delicious food. The princes traveled far and wide seeking the rarest, most delectable foods. The older sons got help from their mothers, but the youngest son received little advice because his mother was dead. One night in a vision, a fairy taught him to make bánh chung and bánh dày. He presented them to his father, explaining that the square, green bánh chung symbolizes the earth and the round, white bánh dày symbolizes the heavens. Impressed by the inherent wisdom in this simple food, the king gave his youngest son the throne.

PANEL 4

Culture in Motion: Dance Traditions

Folk dancing is a cure for nostalgia.

-Guiyuan Wang, Yang Guang (Sunshine) Chinese Dance Troupe, Baton Rouge

Dance traditions flourish in immigrant community life at private family celebrations, nightclubs, and large-scale public festivals and performances. Some dances are vernacular or popular traditions, such as Latino salsa or ballet folklorico. Others are folk dances, like Greek dancing done at weddings and other festive occasions, or classical or court dances such as Indian Bharatnatyam. Deeply rooted in history, traditional dances impart public and private statements about cultural heritage and values, bridging the different worlds in which immigrants live. According to Guiyuan Wang, "Every performance is a package of the traditional music, clothing, life style, customs, aesthetics, and symbols of a people in their regional, social, and natural settings."

Moving Between Worlds: Filipino Tinikling, New Orleans

As far as the social heritage, [we have] had to preserve it as Filipinos. We had to be successful in the general population and also to remain part of the smaller community. It is a balancing act between the public and private life. The thing that would symbolize the Filipinos might be the tinikling—the dance between the bamboo sticks, learning to move in and out of the two worlds with good grace, courage, and humor.

-Marina E. Espina, New Orleans, first female president, Filipino-American Goodwill Society of America, and founder, Asian Pacific American Society

Filipino sailors and navigators began arriving in Louisiana in the 1760s. They adapted seafood–harvesting skills to fishing and shrimping and established "stilt villages"—an architectural tradition adopted by other wetland communities. The last of these, Manila Village, was destroyed in 1965 by Hurricane Betsy. Filipinos continue to emigrate to Louisiana, making them one of the state's oldest and newest populations.

Cultural Heartbeat: Greek Dance, Shreveport

Shreveport's Greek community arrived in response to a series of historical events, beginning with the Greco–Turkish War in the early 1900s, World War II and the Greek Civil War in the mid to late 1940s, and the invasion of Cyprus in the 1970s. Second–generation community member Georgia Booras recalls, "Greek dance was just something you learned within your family. Whether it was a wedding or a baptism or any kind of family celebration, Greek dancing was just always part of it." The community began sharing their dance traditions at public festivals in the 1970s. Today, Greek dance remains the heartbeat of family parties and an expression of cultural pride.

A Balance of Grace and Strength: Chinese Folk Dance, Baton Rouge

New Orleans' Chinatown dates from the 1880s. Following the U.S. ban on Chinese immigration (1882 to 1965), more recent Chinese immigrants have come to Louisiana for educational and professional opportunities. The Yang Guang (Sunshine) Chinese Dance Troupe of Baton Rouge performs folk classical and ethnic dances, connecting performers with their roots, while promoting intercultural communication and understanding in their new home.

PANEL 5

Notes to Live By: Musical Traditions

For many of these Cuban immigrants, the only possession they could bring [to Louisiana], like a precious gem, was their culture and music.

-Tomás Montoya González, sociologist, Santiago de Cuba

From lullaby to hymn to national anthem, music carries people home. It is among the easiest traditions for immigrants to share with the broader community, especially in Louisiana, where music figures prominently on the cultural landscape. The state's vibrant musical terrain is fertile ground for fusion and exploration. The improvisational spirit of jazz-Louisiana's own indigenous musical tradition, itself a blend of influences-embodies the sense of creative adaptation that immigrants embrace to navigate life in a new home.

Garifuna Rhythms of Change and Continuity

The Garifuna sing their pain. They sing about their concerns. . . . We dance when there is a death. It's a tradition [meant] to bring a little joy to the family, but every song has a different meaning. . . . The Garifuna does not sing about love. The Garifuna sing about things that reach your heart

-Rutilia Figueroa, Garifuna elder, New Orleans

The Garifuna of New Orleans are descended from Nigerians who escaped slavery and lived freely among the Carib and Arawak peoples of St. Vincent during the 17th and 18th centuries. In the late 1800s British colonial authorities banished the Garifuna to the Honduran island of Roatán, where they adopted Catholicism and the Spanish language, while retaining their Afro-Caribbean roots. Encompassing multiple generations, the Garifuna in New Orleans began arriving in the 1960s, when political and economic instability at home and the city's strong trade relationship with Honduras brought many to the area for work.

I had the pleasure of sharing my Garifuna culture, and it was very interesting to integrate the Garifuna music with other cultures here in New Orleans, to share in community making. To share in music, in rhythms with other cultures . . . It was a marvelous form of excellence. It makes me realize that we can shine in this place that is New Orleans.

-José Dolmo recalling drumming with local band, Ecos Latinos (Latino Echoes), at the 2008 New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. José came to work on reconstruction following Hurricane Katrina.

QR TO VIDEO OF GARIFUNA DANCE

A Universal Language: Indian Music

Since the 1960s, Indians have come to Louisiana for educational and professional opportunities, with the largest communities in Baton Rouge and Jefferson Parish. Presenting and performing India's classical arts enriches and strengthens the community. Throughout Louisiana, Indian youth are nurtured in their cultural arts through dance schools and music training.

Sitarist Mrs. Meera Seth performs "Bhupali" on sitar, a 25-string lute with a gourd body and wooden neck. Like jazz, Indian classical music is improvised, taking a unique shape in each performance, depending on the circumstances and environment in which it is played. An oral tradition, it is typically passed down in formal teacher-student relationships.

QR TO THIS AUDIO CLIP OF MEERA SETH

PANEL 6

Of Hand and Heart: Crafts and Material Culture Traditions

Crafts and material culture traditions take root less readily in a new country than other art forms. From yarn to hand tools, the lack of necessary specialized materials is an obstacle, although this can lead to creative improvisation. Some artists find that items like handmade shoes or clothes or baskets, once part of life or livelihood in their native cultures, are rendered unnecessary by manufactured goods or a different lifestyle. Even so, the process and pride of making things by hand may in itself be enjoyable, even meditative or healing. Especially evocative of home, material culture traditions take on new value and meaning in a new country.

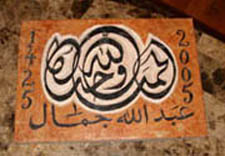

Written in Stone: Arabic Calligraphy and Carving, Baton Rouge

In Palestine calligraphy is in high demand, with many uses, both sacred and secular. In 1990, Ayman Zaben apprenticed in his home country to a calligrapher and stone carver, then combined these skills, carving professionally for mosques, cemeteries, and homes. In Baton Rouge, he machine-cuts stone slabs for his factory job. His hand-carving and calligraphy are gifts he shares with his family and mosque.

Sacred Designs of Hospitality: Indian Rangoli

The rangoli is auspicious as an invitation to the goddess [Lakshmi] . . . a way to honor and welcome all visitors to the home. The rangoli also is created for important family occasions such as weddings for much the same reason, to attract beauty and luck into the lives of the new couple.

-Jayant Jani, Indian Association of New Orleans leader

Rangoli are pictorial or geometric designs made of colored powders or ground chalk, sometimes paint, often incorporating natural materials such as colored rice, turmeric, ground chili, dried dal (lentils), or flowers. The designs are usually circular and symmetrical, and can represent the endless nature of time, the circle of life, or paths of celestial bodies. Women create rangoli outdoors, near the entrance to a home or temple for holidays such as Divali (the Festival of Lights) and other special occasions.

New Year, New Beginnings: Vietnamese Tet, New Orleans

Midnight between the last day of the old year and the first of the new embodies the meeting of winter and spring, of hunger and plenty, and of death and life. Actions that increase good luck or ward off bad luck are emphasized, and correct behavior is followed to begin the new year well. More than a New Year's celebration, Tet is a joyous occasion honoring family values and the cultural community. People gather to enjoy special dishes, watch performances by popular singers and lion dance troupes, and experience the excitement of the first day of the year.

PANEL 7

Life's Seasons and Rhythms: Community Celebrations & Rituals

Often encompassing multiple traditions, celebrations and rituals reflect what is most valued in a culture. Even as they assimilate to life in Louisiana, immigrant communities continue to mark religious observances, commemorations of political or historical events, seasonal or agricultural celebrations, new year's holidays, and personal rites of passage. Public festivals allow immigrants to share their culture with the broader community. Rituals often effect a transformation, marking the passage from one year to the next, from single to married, from youth to adulthood. All such occasions transform ordinary places and time into something extraordinary, if only for a few hours or days.

A Beautiful Leave-taking: Muslim Bridal Henna Parties

In Louisiana's larger cities, Muslim mosques serve multicultural immigrant communities as both a spiritual and cultural gathering place. There is no Islamic culture per se, but rather an Islamic way of life, rich in cultural traditions that vary based on people's native country and ethnicity. Among diverse Middle Eastern Muslim cultures, henna parties figure into pre-wedding rituals. Amid music, dancing, and a traditional meal, the bride and her female family and friends receive henna decorations for the next day's festivities.

Songs to Make the Bride Cry

QR TO AUDIO - TURKISH SONG

Audio: Neslihan Hoover of Bossier City sings "Arda Boylari (The Arda River Narrows)," from her childhood repertoire at henna parties in Turkey. "Arda Boylari" tells the story of a young woman who drowned herself in the Arda River on the eve of an arranged marriage to someone other than her true love.

Passage into Womanhood: Mexican Quinceañera

Since the 1980s, Bernice, a small rural town in Union Parish, has become home to a growing Latino community, many of whom came from the south–central Mexican state of San Luis Potosí for agricultural or poultry processing work. Among the cultural traditions that Mexican immigrants have transplanted from their home country is the quinceañera, an elaborate celebration marking a girl's 15th birthday. The quinceañera begins with a special Catholic mass, followed by a reception featuring live music, dancing, and food.

PANEL 8

A Lot to Learn From Each Other . . . .

A Better Life for All is based on documentary folklife fieldwork conducted as part of the Louisiana Division of the Arts Folklife Program's New Populations Project. From 2005 to 2012, researchers reached out to our state's immigrant and refugee communities to identify and document their traditional arts. Delve deeper into this cultural treasure trove by visiting the New Populations website for essays about the project:

QR link to www.louisianafolklife.org/NewPopulations

QR link to The Many Faces of the Bayou State: New Populations in Louisiana (http://www.louisianafolklife.org/LT/Articles_Essays/newpops.html)

Wimol Harwell of the New Orleans Thai community remembers: My mother began to teach me how to make the krathongs when I was five or six years old. It is important to me because I love the traditions and culture of where I come from. I do not want to lose our traditions, and I want to be able to show people these days. I think people have a lot to learn from each other.

The Louisiana Division of the Arts Folklife Program and the Louisiana State Museum gratefully acknowledge the support of the National Endowment for the Arts, which made the New Populations initiative possible. Thanks also go to the researchers whose work provided the basis of this exhibit and illuminated the state's vibrant immigrant heritage, including:

Kathleen Carlin, Jocelyn Hazelwood Donlon, Laura Marcus Green, Maida Owens, Susan Roach, Amy Serrano, Allison Truitt, Guiyuan Wang, Laura Westbrook, and Daria Woodside. Many other researchers, photographers, and community members participated in the New Populations Project from 2005 to 2012.

Most of all, appreciation is due the traditional artists and community members who so generously shared their knowledge and time and the beauty of their cultural traditions.

Curators

Laura Marcus Green, Guest Curator

Maida Owens, Director of the Louisiana Division of the Arts Folklife Program

Exhibition Designer

Nalini Raghavan