Explore Louisiana's New Populations

Introduction

Chinese

Cubans

Filipinos

Garifuna

Germans

Guatemalans

Hondurans

Indians

Japanese

Laotians

Latinos/Hispanics

Mexicans

Middle Eastern Muslims

Nicaraguans

Thai

Vietnamese

Shreveport - Bossier City

Other Articles on Louisiana's New Populations:

These articles were written through initiatives other than the New Populations Project.

The Many Faces of the Bayou State: New Populations in Louisiana

By Maida Owens and Laura Marcus Green

We live in an era of mobility, in which people move easily from place to place, connecting with family and friends around the world with the touch of a fingertip. The relocation of individuals, families, and cultural communities across the globe can seem almost as instantaneous. The world feels ever smaller, as people leave their homelands to settle in new locations vastly different from their countries of origin. Many of us are descended from such courageous pioneers. For several centuries, political upheaval, economic hardship, or a sense of adventure have driven people from their home countries to a place long known as the Land of Opportunity—the United States.

Louisiana is growing more diverse, as people from around the world make the Bayou State their home. Often referred to as new populations or newcomers, the state's immigrant communities have come from throughout the world. The majority are from Asia and Latin America. The largest communities hail from Vietnam, Honduras, Mexico, Cuba, India, Germany, the United Kingdom, and China. Significant numbers also come from Palestine, the Philippines, Nicaragua, Guatemala, Korea, El Salvador, Japan, Columbia, Pakistan, Nigeria, Laos, and Thailand. Louisiana's largest African community is from Nigeria. Some of Louisiana's immigrant communities represent the national majority of their homeland, as in the case of many Chinese. Others constitute trans-national cultural groups, ethnic communities such as the Garifuna from Honduras, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and Belize, or the Mayans from Mexico and Central America.

Some immigrant groups have come in successive waves, replenishing ties to the home country. Filipinos, for example, were among Louisiana's earliest settlers, with some Louisianans being seventh generation Filipino. New generations of Filipino immigrants continually arrive, to the present day. Similarly, New Orleans' Chinatown formed in the 1880s. However, the U.S. prohibition on Chinese immigration from 1882 until 1965 created a cultural disconnect with the more recent influx of Chinese immigrants coming to the United States, many to attend universities. Croatians from the Dalmatian Coast have been coming to Louisiana continuously since the early 1900s. Typically, the men come to the U.S. to work in the oyster industry, and then often bring over their wives and families to join them.

Other immigrant groups have come to Louisiana much more recently. The Vietnamese began arriving after the fall of Saigon in 1975, during the Vietnam War. Laotians came to Louisiana in the 1980s. Some immigrants have come as groups, while others arrived as individuals or small family units. Some communities continue to bring new spouses or other family members from their homelands. Some immigrants arrive as highly trained professionals who are fluent in English. Others speak only their native languages and did not pursue a formal education in their homelands. Yet the cultural knowledge they bring from their native countries may be the equivalent of an advanced degree or professional apprenticeship.

Demographics Among Louisiana's New Populations

According to the 2000 United States Census,1 2.59% of Louisiana's resident population is foreign-born. This figure includes some residents who have become U.S. citizens. Most foreign-born residents live in urban settings, with the greater New Orleans Baton Rouge areas having the most significant number of immigrant communities. Jefferson Parish—encompassing the Metairie, Kenner and West Bank communities near New Orleans—has a population base of 7.48% foreign born, making it the state's most culturally diverse district, with the largest concentration of almost every immigrant community in Louisiana.

While 36 out of 64 mainly rural parishes recorded one or less percent of immigrant residents, there are notable exceptions. Vernon Parish, with Fort Polk in Leesville, is 4.13% foreign-born. In this case, many military personnel married foreign-born spouses, who then brought their families to live in the U.S. Several other rural parishes across southern Louisiana have culturally diverse communities, but otherwise, most immigrants living in rural communities are Mexican.

It is difficult to generalize about the various immigrant communities in Louisiana. Each of their situations is unique. Yet in spite of their diversity, most immigrants have come for similar reasons: economic, educational or professional opportunity, or political freedom and safety. The state's hospitality industry is a draw, bringing a multicultural work force to find employment in casinos and resorts, while universities and medical centers throughout the state have attracted many international community members who come for educational and professional development. Louisiana's recent natural and manmade disasters also account for demographic shifts. Following Hurricane Katrina, a large number of Latino immigrants arrived in coastal areas to assist with clean-up and rebuilding. Likewise, the 2010 oil spill off the Louisiana coast brought Latino workers to assist with clean-up operations. As this work dwindles, new opportunities beckon people to the state's inland areas to seek employment in hospitality, agriculture, and other industries.

It is also difficult to accurately determine the size of many immigrant communities. For example, since Hispanics are included in reports on race, more information is available about their demographics. However, these statistics do not address the details of people's culture or nationality. The U.S. Census does not include many nationalities in its report, Ancestry Profile 1: First and Second Ancestries Reported. The most useful report for ascertaining national identity is the U.S. Census document, Ancestry Profile 3: Place of Birth for the Foreign-Born Population,1, which is published in the third year of each decade. This report does not include the children and grandchildren of immigrants who self-identify as part of these communities. However, it does give a sense of a community's cultural demographics by providing a count of its foreign-born residents.

The Cultural Communities and Where They Live

The Vietnamese are the largest immigrant community in the state. Most parishes, especially across south Louisiana, have some Vietnamese residents, with the largest concentration being in Orleans and Jefferson Parishes, followed by Baton Rouge. The largest Latino community is from Honduras; here again, most are in the greater New Orleans and Baton Rouge areas. Mexican residents live in most parishes throughout the state, both urban and rural. While their numbers have dramatically increased in recent years, some communities have been here for decades—in particular, in Forest Hill in Rapides Parish and Bernice in Union Parish. Indian residents live in all urban centers of the state and many rural communities, with the largest numbers in Baton Rouge and Jefferson Parish. Cubans concentrate in the greater New Orleans area and Baton Rouge. Germans, Canadians, and those from the United Kingdom are primarily in urban and suburban parishes. Chinese live predominantly in urban areas, with smaller communities in rural areas. Many of the state's immigrants from Western Asia are displaced Palestinians who have settled in primarily urban areas.

Filipinos, Nicaraguans, Koreans, Salvadorans, Japanese, Columbians, Pakistanis, Nigerians, and Panamanians all concentrate in the greater New Orleans and Baton Rouge areas. French foreign-born live primarily in southern Louisiana's urban areas. Others from Thailand, Trinidad & Tobogo, Jamaica, Venezuela, Costa Rica, Brazil, and several Eastern European countries also concentrate in urban areas. One exception is the Laotian community near New Iberia, which is primarily a rural area.

Art Forms and Traditions Maintained by New Populations in Louisiana

The New Populations Project revealed much about Louisiana's immigrant communities and the remarkable array of cultural traditions that they have maintained here. These include foodways, dance, music, crafts, community celebrations, and rites of passage. Traditional arts gather immigrant communities together, while offering them a means of sharing their cultural heritage with the broader populace. Traditional arts highlight our cultural distinctiveness, often illuminating worlds within worlds, for the cultural enclaves they reveal.

Some folk arts are practiced by many within an ethnic community. Traditional cooking, for example, represents a form of portable and enduring knowledge. People tend to prepare the cuisine of their native country or region long after they arrive in a new home, passing favorite recipes down through families. Other cultural traditions are more specialized and are maintained in the hands of individuals who may be among the only people in their community to carry the torch for future generations. Individual folk artists often bring joy to others through their expertise, while fulfilling a vital service in the social, spiritual, or political lives of their cultural communities. These roles become especially important in diaspora, when people are far from their home countries.

Foodways are always the traditions most resistant to change. We definitely are what we eat and immigrants will go to extreme lengths to continue eating their traditional foods. Many have home gardens that provide produce not found in chain grocery stores. Ethnic groceries are among the first businesses to open, once there are sufficient residents in a community to support them. Restaurants closely follow. Foodways documented by the New Populations project include Nicaraguan tamales, Mexican celebratory foodways, Vietnamese cánh phuong (phoenix wings) for Tet, German bread, Greek Orthodox ritual foods, and Bosnian bread.

Dance is often retained in immigrant communities because it figures into community celebrations and provides opportunities to gather socially. Dance costumes are often important private and public statements about cultural heritage. Some dances may be vernacular or popular traditions, such as salsa or ballet folklorico. Others are folk dances, such as those performed by the Hellenic Dancers of St. George in Shreveport, or classical or court dances such as Bharatnatyam, a form of Indian classical dance.

Some dance traditions are associated with private holiday celebrations, including garba, raas, and dandiya, which are performed at the Hindu Navaratri celebration. Others figure into public performances, either at festivals such as the Asian Pacific American Society's Asian Heritage Festival in New Orleans, or in more formal theater productions, such as the Yang Guang (Sunshine) Chinese Dance Troupe. Other dance traditions documented among Louisiana immigrant groups include Japanese minyo, as well as Cuban son and Filipino pandanggo sa ilaw dance.

Music is, of course, important to practically any culture and is found in many settings from festivals to concert halls, and from religious settings to private family celebrations. Musical traditions were documented in Louisiana at such events as Indian classical music concerts and Latin music festivals and dance clubs, among others. Traditional artists who shared their heritage include a Guatemalan guitar duo, Mexican church choirs, and Cuban musicians. Honduran music, Garifuna drumming, Turkish traditional song, and songs sung to the Blessed Mother for La Purisima-a significant spiritual and cultural celebration on the Nicaraguan calendar-are among the musical traditions documented for the project.

For several reasons, craft traditions and material culture are perhaps the least likely art forms to be maintained among immigrants living in diaspora. Even if they know how to make things that were one part of life in their home culture, people are often too busy to do crafts as they adjust to a new home. Also, occupational art forms like tailoring or shoemaking that were a necessity in some people's home countries are considered luxuries in the U.S., where people tend to buy inexpensive, manufactured versions of these items. Many material culture traditions require specialized materials or tools that may be difficult to impossible to find in the United States. Those immigrant traditional artists seeking to earn money from their work may find that it is difficult to compete with the market for imported crafts. Because of these factors, items made back home are often more highly valued by immigrants living in the U.S., and the role of crafts may change in the new setting. In spite of all these considerations, some do continue to make crafts, especially those associated with ritual or holiday celebrations.

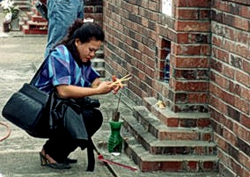

Crafts and material culture traditions documented in Louisiana include Palestinian stone carving, Mexican piñata making and ofrendas (home altars), Chinese paper folding and knotting, Laotian altar offerings, Vietnamese altars, Hindu rangoli and garland making, Thai krathongs used for Loy Krathong-Festival of the Floating Lotus, Vietnamese lanterns for Tet Trung Thu, Greek Orthodox iconography, and Laotian architectural woodcarving. Women's handwork traditions are often retained in the home. Handwork traditions documented for the New Populations project include Mexican crochet, Croatian embroidery, Honduran needlework, Greek embroidery, and Palestinian cross stitch.

Community celebrations and rites of passage are often maintained because of their importance to community identity. Most cultural events include multiple traditional art forms, including music, food, and often dance or crafts. Community celebrations documented for the New Populations Project include Chinese, Vietnamese, Laotian New Year celebrations, Nicaraguan La Purisima and La Griteria, and Vietnamese Autumn Festival Tet Trung Thu. Rites of passage documented include Cuban birthday parties, Mexican quinceañera and baptism ritual celebrations, and Vietnamese Autumn Festival Tet Trung Thu.

Conclusion

The United States is often called a "nation of immigrants" and a "melting pot." Each generation of immigrants brings its own ingredients to the stew. American culture is made up of many flavors that find their way into the mainstream cultural repertoire, be it through sampling new fare at ethnic restaurants, exploring world music, donning internationally inspired clothing, or stepping out to dance styles like salsa and Bollywood. For ethnic and immigrant communities, these traditions are a powerful thread connecting them with their cultural roots. Even though the cultures mingle and influence one other, each maintains traditions uniquely its own. With each cultural group that arrives, Louisiana's tapestry of cultures is enriched.

Some New Populations articles have field reports that are available upon request. These are indicated by an asterick * in front of the expanded list of titles above.

See A Better Life For All: Traditional Arts of Louisiana's Immigrant Communities, a virtual exhibit.

Footnotes

1. 2000 United States Census, Ancestry Profile 3: Place of Birth for the Foreign-Born Population. Louisiana.