Crescent City Country: Hillbilly Music in New Orleans

By J. Michael Luster

Mention music and New Orleans and many will think of that city's important legacy of jazz, brass bands, Mardi Gras Indians, and rhythm and blues. Few will recognize the role of country music in the city's musical landscape. But in the spirit of the Country Music Foundation's recent survey of R&B in Nashville, it seems it may be instructive to explore the place of country music in this quintessentially Southern city. In this brief presentation, I will touch on country music from New Orleans, country music in New Orleans, and country music about New Orleans.

"Country music" as a label is often applied retroactively to the mixture of early stringbands, vocal music, and related forms that existed primarily in the South in the days prior to commercial recording. Few descriptions of these forms have been uncovered from early New Orleans. The few exceptions include the recollections of Jelly Roll Morton as recorded by Alan Lomax in 1939. Morton described the Black and Creole serenading stringbands active in the City prior to 1900 and the vocal quartets that sang spiritual numbers primarily for funerals and wakes. He also singles out the work of one Kid Ross, an outstanding white player of hot piano in the Storyville district around 1910. Unfortunately, no recordings of New Orleans music exist prior to 1917 when the white players who made up the so-called Original Dixieland Jazz Band recorded "Livery Stable Blues" for Victor.

With the boom in the recording of vernacular music that followed came the first country music recordings made in New Orleans. I am indebted here to the exhaustive discography of New Orleans recording sessions compiled by Ron Sweetman. The first session held in New Orleans was done by the Okeh Record Company in March of 1924, recording four jazz bands, a blues singer, and a black vocal quintet singing "Give Me That Old Time Religion." The first identified country music recording session in New Orleans is from April, 1927, the first of several sessions there by the Leake County Revelers of Sebastopol, Mississippi. They preceded by several months the historic sessions by Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family at Bristol, Tennessee.

Rodgers had actually spent a great deal of time in New Orleans before he ever entered a recording studio. Beginning as early as 1920 he was a frequent visitor to the city while he worked as a brakeman on the New Orleans and Northeastern Railroad on its regular run from Meridian, Mississippi, to New Orleans. He may have visited the city even earlier and would have been attracted to city's mix of music and the sporting life. One of his earliest recordings was an original piece "My Little Old Home Down in New Orleans" from June of 1928. Rodgers recorded "Hobo Bill's Last Ride" in New Orleans in 1929 and a year later recorded with the city's best-known native son, trumpeter Louis Armstrong, and his wife pianist Lillian Armstrong in one of the earliest integrated recording sessions.

On April 27, 1928, the Leake County Revelers again entered a makeshift New Orleans studio and recorded their version of "Make Me a Pallet on the Floor," a song that was a staple among New Orleans musicians black and white since the days of Buddy Bolden. On that same day, another page of country music history was made. The first ever Cajun record was made there by Joe and Cleoma Falcon with "Allons a Lafayette." New Orleans would become the leading city in the recording of rural Cajun music, much of it heavily crossed with the flavors of Western Swing, like the 1930s recordings of the Hackberry Ramblers and Happy Fats.

Western Swing, another posthumously applied musical term, is dated by some to the 1929 recording debut of Bob Wills which coupled a fiddle breakdown with a cover of Bessie Smith's "Gulf Coast Blues." Wills was especially fond of New Orleans jazz, and he played and sang in a manner that drew heavily on New Orleans style and repertoire. As he and his band the Aladdin Laddies (later the Light Crust Doughboys and then the Texas Playboys) developed their sound in the dance halls and radio studios of Fort Worth, they drew heavily on jazz material including "St. James Infirmary," "Basin Street Blues," "Jelly Roll Blues," and " The Darktown Strutters Ball." While this hybridization was in many ways pre-figured by Jimmie Rodgers, for Wills it accelerated when he teamed up with fellow jazz lovers Durwood and Milton Brown in the years between 1930 and 1932. The Brown brothers left the Light Crust Doughboys in the year 1932 and formed what is considered the first true Western Swing band, Milton Brown and His Musical Brownies. Among the band's hallmarks were the use of jazz soloing, including the first electric guitar, and a repertoire that drew heavily on New Orleans and other jazz material.

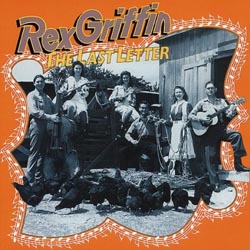

Beyond its Texas base, this reflected New Orleans music (coupled with that of Jimmie Rodgers) seems to have been especially popular in Alabama and Louisiana. Rodgers imitators abounded including New Orleans' Jerry Behrens and Quitman, Louisiana native and future governor Jimmie Davis. One of the most influential was Alabaman Rex Griffin, who relocated to New Orleans in the years following the tragic death of Rodgers. Griffin began broadcasting over the 100,000-watt radio station WWL that blasted up the center of the nation carrying a mix of hillbilly music and patent medicine advertisements. Among Griffin's most influential recordings was "Everybody's Trying to Be My Baby," (later covered by western swinger Roy Newman, rockabilly architect Carl Perkins, and in 1965 by the Beatles). Others included "The Last Letter," and his 1939 remake of "Lovesick Blues" a recording that would be copied closely a decade later by fellow Alabama-to-Louisiana migrant Hank Williams. In addition to Griffin, others who traveled to New Orleans to perform and broadcast in the new jazz-inflected country style included Hank Penny, Curly Fox, and the Shelton Brothers all of whom joined Lew Childre on WWL in disseminating the music via its strong clear channel. Shortly before his own tragic death, Milton Brown traveled with his band to New Orleans and recorded forty-nine sides including versions of "Keep Knockin' (But You Can't Come in)," "Mama Don't Allow It," and "Sadie Green (the Vamp of New Orleans)." Had he not been killed in an auto accident six months later, it might well have been Milton Brown and the Musical Brownies?with the keening electric steel guitar of Bob Dunn?who would be remembered as the kings of western swing. Tellingly, when the Brownies again entered a studio to record after their leader's death, it was Jimmie Davis (who would literally reign over Louisiana's country music in the 1940s) that took the lead vocals on "High Geared Daddy" and "Honky Tonk Blues."

As the 1940s dawned, ten-year-old Harold Cavallero was rolling a tire down the street with a stick when he was about to have his own encounter with the keening steel guitar. As he tells the story, a man drove up and asked if he wanted to play a guitar. Harold thought he was going to give him one on the spot but it turned out the man was rounding up customers for Roger Filiberto who was teaching lessons at Werlein's Music Store on Canal Street. Filiberto would go on to literally write the book on the electric lap steel guitar and the electric bass first for Gibson Guitars and then for Mel Bay instructional books and would teach countless players both directly and indirectly before his death at the age of 94 in 1998. In 1941 he was offering a year's worth of lessons to youths like Cavallero, and at the end of the year they got to keep the guitar. Cavallero proved an apt student and by the time he was thirteen he was a working professional playing at Betty's Tavern on Decatur Street. By the following year he was playing on radio station WJBW with fiddler and bandleader Danny Powell, who had some four or five country bands working around the city of New Orleans.

World War II was on and New Orleans had become the most important shipbuilding city in the world. One shipyard alone, that of Andrew Jackson Higgins, accounted for 63% of all boats in use by the US Navy in 1943. The company had grown from just 50 employees in 1937 to 1600 by 1941. These new employees came from Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama, Texas, and northern Louisiana and with them came a strong interest and opportunity for country music to the point that, as one disgruntled jazz fan wrote, that hillbilly singers and Irish tenors threatened to displace jazz entirely. By 1944 a country-music fueled campaign landed Jimmie Davis in the Governor's Mansion. People liked to tell how he brought his horse into the building, marking the first time there was a whole horse in the Governor's Mansion.

One of the laborers who came to New Orleans to work the shipyards was Werly Fairburn from Folsum, Louisiana, up above Lake Pontchartrain. Fairburn worked at the Higgins Shipyard, joined the Navy, and trained as a barber on his return to New Orleans after the war, later landing a program as "The Singing Barber" on WJBW. He later moved to WWEZ as "The Singing DJ." Meanwhile, station WDSU had begun a weekly Dixie Barn Dance hosted by one Uncle Roy. The program was a showcase for the city's burgeoning cast of hillbillies and singing cowboys. One of the local stars in 1947 was fourteen-year-old Betty Owens, later to become the featured vocalist with the Dukes of Dixieland, illustrating again the sometimes fluid boundaries between musical forms. Harold Cavallero had joined the house band on the Dixie Barn Dance in addition to his active work in the nightspots that featured hillbilly music along with other fare. There were names like the Silver Star, the Ali Baba, the Cadillac Club, the B & T, the Rainbow Lounge, the Fun House, the Gay Paree and many more. He tells of playing a regular Sunday afternoon gig at the Moulin Rouge across the river in Algiers and sticking around to listen to jazz pioneer Papa Celestin who performed after them. On another occasion, he slipped in backstage at the Municipal Auditorium and had the chance to meet a singer named Hank Williams. It was April 6, 1951, and the bill also included Lefty Frizzell and the Callahan Brothers.

Williams had come to Louisiana in 1948 from Alabama to play on the state's other great clear channel radio station, Shreveport's KWKH home to the highly influential Louisiana Hayride stage show and broadcast. Williams drew heavily on Louisiana material with such numbers as "My Bucket's Got a Hole in It," his own setting of a ballad-like poem "On the Banks of the Old Pontchartrain," his collaboration with Jimmie Davis on "Bayou Pon Pon," and with Davis's campaign piano player Moon Mullican on "Jambalaya," as well as his career-making cover of "Lovesick Blues"; Williams used the song as a springboard and it propelled him to the Grand Ole Opry and stardom, but by October, 1952, he had slid back to Louisiana and returned to New Orleans for the bizarre spectacle of his marriage to a Bossier City girl at the Municipal Auditorium that required two seatings. He would be dead before the year was out.

After his death, there was no shortage of those who would seek to fill his shoes including such regional talent as Jimmy Swan and Luke McDaniel, and New Orleanian Werly Fairburn. Fairburn recorded some Williamsesque numbers for Jackson-based Trumpet Records (including the "Jambalaya" inspired "Camping with Marie") before he was picked up by Capitol and then by Columbia Records. By then, Harold Cavallero had joined him as steel guitarist and even traveled to Nashville to record Fairburn's "I Guess I'm Crazy," a song that would inspire many cover versions including a posthumous hit for Jim Reeves. They played the Hayride, and Fairburn was asked to join the program as a regular. Cavallero declined to go with him in deference to his family and his steady income day job. He chose wisely, for another charismatic performer had recently joined the Hayride and used it as a base to launch his own national career. That was, of course, the proto rockabilly Elvis Presley and it wasn't long before Werly Fairburn had a rockabilly hit of his own with "Everybody's Rockin'," recorded without a steel guitar anywhere in sight. Cavallero had actually played on the same program with Elvis in 1955 when he had come to Pontchartrain Beach Amusement Park as part of a Hayride package show, but very soon the stripped down rockin' 1950s were the order of the day. Actually the fill-in drummer that day at Pontchartrain Beach was another New Orleans hillbilly turned rocker, Joe Clay who quickly landed his own deal with RCA's Vik label and made it to the Ed Sullivan show before the winds changed yet again.

Harold Cavallero stuck with his steel and worked the clubs and knock-off hayrides of New Orleans and the surrounding countryside. Up above the lake there was the Pontchatoula Hayride, the Big Howdy Jamboree was in Bogalusa, and the Wego Country Opry was over on the West Bank, where many of the country fans had moved as they left the city for the surrounding towns of Metairie, Westwego, Harvey, and Slidell. Just across the state line in Picayune, Mississippi, Byron "B. J." Johnson worked as a deejay, singer, and talent scout for Houston-based D Records. Johnson was the namesake for the Stonewall Jackson hit "BJ the DJ," and many of the New Orleans hillbilly players recorded for him and did occasional sessions at Cossimo Matassa studio, one much better known for its work with rock and rhythm performers like Fats Domino, Little Richard, and Lloyd Price.

There was a small resurgence of interest in country music in the 1960s, and a brief flirtation with country rock in the 1970s, but with the flowering of the New Orleans R&B revival in the mid 1970s the city's country music heritage was largely forgotten. The music had become the marker of a largely departed population. By 1980, the city's white population had shrunk to pre-Civil War levels. New Orleans is now seen as solely an Afro-Caribbean city, the northernmost reach of island-style ease and license. While this is certainly true, what is all but forgotten is that it is also our most Southern city, was once home to thousands of migrant Southern workers, and the natural habitat of much of the music we have come to call country.