Country Chameleons: Cajuns on the Louisiana Hayride

By Tracey E. W. Laird

Cajun musicians and country musicians have exchanged musical ideas at least as early as the late 1920s, when records by both first became widely available. Both Cajun and country artists began incorporating elements from the other style into their own musical repertoires. For example, the early 1930s recordings of Cajun musicians Joe and Cleóma Falcon include Cajun French translations of Carter Family songs like "I'm Thinking Tonight of My Blue Eyes" and "Lu Lu's Back in Town." Leo Soileau recorded "Personne m'aime pas," translated from the song by Jimmie Davis, "Nobody's Darlin' But Mine." Some Cajun bands began adapting country instruments like the electric steel guitar and the trap drum set, which by the 1940s were standard alongside the traditional fiddles, guitars, accordions, and assorted percussion.

Cajun music gradually made its way to the ears of mainstream country musicians, beginning with the first commercial Cajun release, the Falcons' "Allons á Lafayette" in 1928. But it would take nearly two decades before a South Louisiana musician received wide notice. Guitarist, fiddler, and singer Harry Choates was born near Rayne, Louisiana, but lived much of his life in Port Arthur, Texas, where he moved to work in the oil industry. There he became a regional favorite in honky-tonks throughout Southwest Louisiana and in the Texas region known as the "lapland" (for the overlap of Cajun culture there). Choates' 1946 version of "Jole Blon" was a huge regional hit, and his influence extended up into North Louisiana and beyond. (The earliest version of this song, called "Ma Blonde est partie," appeared on record in 1928 by the Breaux brothers, Amédé, Ophé, and Cléopha, in-laws of Joe Falcon.)

Choates inspired other country artists, including the late Roy Acuff and the legendary pianist and singer Moon Mullican, who was also from the lapland. Later in 1946 Mullican released "New Jole Blon." This song was based on the Choates version, but because Mullican did not understand French, he replaced the original lyrics with things like "possum up a gum stump." Mullican tried to build on the popularity of this song with the lesser-known follow-up, "Jole Blon's Sister."

This process of musical borrowing and exchange continued in 1948 with the beginning of the Louisiana Hayride in Shreveport, Louisiana. The Hayride was North Louisiana's forum for country music during the postwar era. Broadcast from the Municipal Auditorium over the 50,000-watt station KWKH, the Louisiana Hayride launched some of the greatest careers in country music from 1948 until 1960. It blasted throughout north and south Louisiana, as well as more than twenty-five other states, and gave numerous musicians their first national exposure. In fact, KWKH nurtured so many successful country music careers that it came to be called the "Cradle of the Stars."

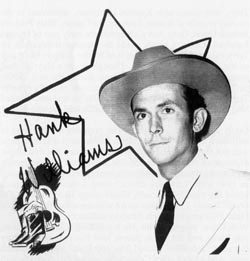

Known for its experimental attitude and its openness to artists who stretched the boundaries of country music, the Hayride introduced to the nation some of country music's most unique and influential voices: Hank Williams, Webb Pierce, Kitty Wells, Elvis Presley, George Jones, Johnny Cash, Jim Reeves, Johnny Horton. A wide variety of artists appeared on the Hayride stage—from honky-tonkers to crooners to rockabillies—so that KWKH played a part in shaping or popularizing a number of styles, all within the context of a country music radio show. Among the variety of artists who appeared on the Hayride were musicians from South Louisiana who played pure Cajun songs or country songs that reflected the musician's Cajun roots.

A handful of highly-respected Cajun musicians graced the Louisiana Hayride stage from time to time. One of the most commercially successful of these south Louisiana musicians was Jimmy C. Newman, who first appeared on the Hayride in June 1954 and went on to spend 43 years on the Grand Ole Opry. Born in 1927 on the prairies of Big Mamou, Louisiana, Newman began his professional music career in 1946, as singer in a band that played country and some Cajun music in clubs around Bunkie, Louisiana. With this band, led by fiddler Chuck Guillory, Newman made his first recordings in 1946, singing mostly Cajun songs in his native French patois.

Country songs influenced Newman from his early childhood, when he and his brother Walter listened to old phonograph records by the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers, and to the Grand Ole Opry on radio on Saturday nights. By the late 1940s and early 1950s Newman started experimenting with a mainstream country sound. He acquired a songwriting contract from Acuff-Rose, which led to a deal with Dot Records. Newman's first major hit, "Cry, Cry, Darling'" in 1954 reached the top five on the country chart and led to an invitation to join the Louisiana Hayride. Newman's country hits continued, including "Daydreamin'," "Blue Darlin'," and "God Was So Good" in 1955, and "Seasons of My Heart" in 1956. Like so many Hayride artists before him, he left Shreveport to join the Grand Ole Opry in 1956, and continued to chart songs, the biggest of which, "A Fallen Star," crossed over to the pop chart as well.

During his two-year stint at the Hayride, most of Newman's repertoire was mainstream country; the one exception was the song "Diggy Liggy Lo," which was a Cajun melody given words in English. After switching from Dot to MGM Records in 1958, Newman began experimenting with blending Cajun and country styles. In 1961 and 1962, respectively, he recorded "Alligator Man" and "Bayou Talk," both country songs that recalled the singer's Cajun roots. In 1964, Newman recorded for Decca his first album of Cajun music in almost fifteen years, called Folk Songs of the Bayou Country, which featured acoustic instruments only, and included Rufus Thibodeaux on fiddle and Shorty LeBlanc on accordion. Since that album, Newman has performed as an ambassador of Cajun musical culture in places like the Wembley Festival in London and the Smithsonian Festival in Washington D.C. At the same time, Newman continued to excel as a performer of mainstream country, with hits like "DJ for a Day," "Artificial Rose," "Back Pocket Money," and "Louisiana Saturday Night."

In 1970, Newman recorded an album for the small label La Louisianne, which included the first song in Cajun French to become a gold record, "Lache Pas La Patate" ("Don't drop the potato"). Largely ignored in most of the United States, this song was a hit in South Louisiana and French Canada, especially Quebec. In the late 1970s, Newman put together a band called Cajun Country that included his son Gary Newman, fiddler Rufus Thibodeaux, and accordionist Bessyl Duhon. His band still performs on the Grand Ole Opry today. And his repertoire has come full circle. With the exception of his biggest country hits, Newman's band performs "about 99 percent Cajun" these days.

Another Cajun musician who made waves throughout the world of country music was fiddler Doug Kershaw. Along with his brother Rusty, Doug Kershaw appeared on the Hayride from 1955-56. Together, the Kershaws created a frenetic blend of Cajun and rockabilly, which they carried to the Wheeling Jamboree in West Virginia in 1956 and to the Grand Ole Opry in 1957. The brothers then joined the Army for a couple of years, and returned in 1960 to record their biggest hit as a duo, "Louisiana Man." They recorded a few more hits together in the early 1960s, including a version of "Diggy Liggy Lo" and "Cajun Stripper." In 1964, they decided to split up their partnership.

Doug Kershaw emerged as a solo performer, beginning with an appearance on the television debut of the Johnny Cash Show in 1969. Throughout the 1970s, Kershaw, alternately known as "the Ragin' Cajun" and "the Cajun hippie," continued melding together Cajun music and rock 'n' roll through his fierce fiddle style—with the instrument cradled in his armpit—that delighted audiences as much as his velvet suits and wild stage antics.

Other Cajun musicians appeared on the Louisiana Hayride, each concentrating for the most part on mainstream country, but sometimes recalling their South Louisiana roots. These artists attest to the long-standing rapport between Cajun and country musical styles, both vital genres that easily adapt to one another. Singer Thibodeaux "Tibby" Edwards, for example, appeared on the Hayride from 1952 until 1958, when he joined the Army. Despite Edwards's Cajun ancestry, he most often performed honky-tonk music more reminiscent of Hank Williams or Lefty Frizzell. Yet, he demonstrated his flexibility while on the Hayride, recording in several styles during the 1950s—honky-tonk, rockabilly, and Cajun. Commercial success came with two rockabilly releases in 1955, "Flip, Flop, and Fly," and "Play It Cool, Man, Play It Cool." Edwards' Cajun release also sold well, "C'est Si Tout," which was co-written by Leon Tassin.

The late singer/guitarist Allison Theriot, better known as Al Terry, was raised near Kaplan, Louisiana, immersed in the country records of Jimmie Rodgers, the Carters, Riley Puckett, Jimmie Davis, Gene Autry, alongside the early jazz of Django Reinhart. Country music made the deepest impression on Terry, especially the smooth style of Western singers like Autry or the Sons of the Pioneers. Though never a Hayride cast member, Terry was a featured guest during the mid-1950s, performing in a crooning style reminiscent of Eddy Arnold. Terry's biggest hit was "Good Deal Lucille"—a song that reflected his Cajun roots in its mixture of French and English lyrics.

Oddly enough, the performer who probably did the most to introduce Cajun musical style to mainstream country music was not Cajun at all. Hank Williams gained his first major exposure on the Louisiana Hayride, and he had a deep affection for Cajun culture. Even before he rose to national prominence in 1949 with "Lovesick Blues," South Louisiana audiences loved his music, especially ribald songs like "Move It On Over." Jimmy C. Newman spoke with me about the appeal of Hank Williams to French Acadian audiences:

"With Cajun people,

he hit. He was telling it the way it was, you know, and the

Cajun people love that real sincere story in a song. "Jole

Blon" proved that "Jole Blon" was a heartbreak

song. And a lot of other Cajun songs, songs I've done through

the years."

When Williams released "Jambalaya (On The Bayou)" in

1952, it was immediately popular not only with Cajun audiences,

but all over the country. The song was taken from the 1946 Cajun

melody "Gran Texas" by Chuck Guillory (with whom Newman

played). Williams then wrote lyrics with Moon Mullican. Like

Terry's later hit, "Jambalaya" was a hodgepodge of

French and English lyrics set to an Acadian groove, intended

to evoke the spirit and aesthetic of Cajun music while remaining

friendly to a mainstream country audience. The song became immensely

popular and was eventually recorded successfully by artists as

divergent as Fats Domino and John Fogerty.

Not only was one of Williams's best-known tunes derived from a Cajun song, but fellow KWKH-Louisiana Hayride star Kitty Wells, the "Queen of Country Music," is also popularly known for a song written by a Cajun. Crowley-based producer and songwriter J.D. Miller, who recorded Cajun artists like Newman, Kershaw, and Terry on his Feature Records, wrote "It Wasn't God Who Made Honky-Tonk Angels," which Wells popularized in 1952. That same year, Wells left Louisiana and the Hayride, as so many eventually did, for Tennessee and the Opry. Eminent Cajun-country artists came into their fame via the Louisiana Hayride, and other regionally popular performers appeared on the show, including south Louisianians Happy Fats (guitar) and Oran "Doc" Guidry (mandolin and fiddle), as well as fiddler Buddy Attaway, a Shreveport native who performed Cajun classics such as "Poor Hobo," and his own Cajun-style compositions such as "I'm Going Back to Cloutiersville." Even so, the songs "Jambalaya" and "It Wasn't God Who Made Honky-Tonk Angels" just may be the most far-reaching contributions of Cajun culture to mainstream country music by way of Shreveport's Hayride stage.

Sources

Ancelet, Barry Jean. Cajun Music: Its Origins and Development. Lafayette, LA: The Center for Louisiana Studies, University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1989.

Broven, John. South to Louisiana: The Music of the Cajun Bayous. Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing Company, 1987.

Escott, Colin. Hank Williams: The Biography. Toronto: Little, Brown and Company, 1994, 1995.

Green, Douglas B. "Jimmy C. Newman and his Cajun Country Roots," Country Music 7, no. 7 (May 1979): 20, 66, 68.

Malone, Bill C. Country Music, U.S.A.: A Fifty-Year History. 2d rev. ed. Austin: The University of Texas Press, 1985.

McCloud, Barry. Definitive Country: The Ultimate Encyclopedia of Country Music and Its Performers. New York: The Berkley Publishing Group, 1995.

Newman, Jimmy C. Interview with the author. 27 July 1999.

Tucker, Steven R. "Louisiana Saturday Night: A History of Louisiana Country Music". Ph.D. diss., Tulane University, 1995.