Sacred Sounds in Baton Rouge Churches, Synagogues, Temples, and Mosques

By Maureen Loughran

We do it from the heart to edify God's holy name. . . . We all enjoy and do it from the heart, not for fashion or show.

—Joseph Anthony, Greater St.

James Men Singers, Baton Rouge, La.

Baton Rouge is typical of many cities of the South, in that church, irrespective of denomination, is an important facet of everyday life, especially on Sundays. There can be found churches dedicated to Christian faiths, whether that be Baptist, Presbyterian, Catholic or Orthodox. Synagogues, mosques and Buddhist temples also provide spiritual guidance to the population of the Capital City. This fieldwork project was an attempt to document sacred music traditions in Baton Rouge, and particularly the song leaders or music directors at various religious institutions. The project also developed a focus on chanted religious expressions (whether considered musical by the denomination or not), from Greek Orthodox chant to recitation of the Qur'an. The following essay explores the different ways in which religious institutions in Baton Rouge support musical traditions within their organizations, including religious denominations less dominant in the Southern spiritual landscape.

Chanters and Reciters: Islamic, Orthodox and Buddhist Traditions in Baton Rouge

The most basic form of ritual can be found in the recitation of religious texts. In some communities, this recitation is expressed musically through chant. In others, like Islamic cultures, music is a secular endeavor and therefore not an appropriate term for describing the rendering of holy words into speech. In Baton Rouge, you can find various approaches to the recitation of sacred texts in Christian churches, Jewish synagogues, Buddhist temples and Muslim mosques.

Qur'an Recitation

At the Masjid Al-Rahman campus of the Islamic Center of Baton Rouge, the recitation of the Qur'an is a central facet of the education of their youngest members. Each Saturday, the mosque holds a Qur'an and Taribiya School for children as young as pre-school age. Taribiya School involves the teaching of manners and values, while in the Qur'an recitation class, students learn not only how to recite the Qur'an but also spend time discussing the text they are reciting. Dr. Ömer Soyal, an assistant professor of computer science at Louisiana State University, directs the school to address both manners and religious recitation because as he says, "Islam is all about the true belief and the good manners. It's the complete package" (Soysal 2016). And while recitation may imply that the material is to be memorized, Dr. Soysal insists that the goal is instead to provide understanding. By learning how to recite the text, the student begins to uncover the meaning of the text. Memorization aids in understanding and provides a structure to practice of religious faith in everyday life.

A visit to the school at Masjid Al-Rahman is reminiscent of any after-school program you might find at a community center or church hall. Parents drop off children, varying in ages from pre-school to middle-school, who pile into the all-purpose room, finding friends and digging through lunch boxes before gathering into lines for their classes. The student recite a prayer in both Arabic and English affirming "I am a Muslim." Then, they move to their respective classrooms where they learn different aspects of Islamic traditions. In one of the middle school classrooms, the students sit at two tables, girls on one side, boys on the other. The class is led by Dr. Soysal's son, Hanif, who is a student at LSU. That day, the class was learning the 104 surah or verse of the Qur'an. Hanif started the lesson by reciting part of the verse, which the students would repeat, step by step until the entire surah had been recited in Arabic. If the students were confused by the text or having trouble with pronunciation, Hanif would say the verse with deliberate emphasis, slowly speaking the text with the student. Once they had confidence with speaking, the students would listen to Hanif recite the verse with melodic emphasis and they would repeat.

Dr. Soysal reminds us that while recitation may sound like it has a melodic element to it, the recitation of the Qur'an is not considered to be a musical event. In fact, there is a clear division between the music as secular and recitation as sacred. He explains:

We avoid music traditionally because of the way it is used. Abused, actually we'd say. But definitely there is a rhythm in the Qur'an that effects the heart actually. Because if you listen to a reciter, from reciter to reciter you will see the difference, the effect on your heart. . . . Really, the Qur'an has its own type of rhythm. Especially rhythm that touches the heart. (Soysal 2016)

Suleiman Suleiman, a graduate student at LSU and a native of Saudi Arabia, is considered by Dr. Soysal to be one of the best reciters of the Qur'an in Baton Rouge currently. Suleiman grew up in Medina, one of the most holy cities in Saudi Arabia, and home to many students of the Qur'an and their teachers, known as sheiks. Suleiman's father was one of these teachers, and Suleiman began studying with his father at a very young age. Suleiman explained the process:

I started with a little bit each day, but it had to be every day. So every day with my father I would sit for two or three hours in the afternoon and he would, like, teach me the small verses, small surahs. Once I went into first grade, . . . I had a schedule every day. So in the morning I would go to school, and then come back in the afternoon and rest a little bit and then around this time or even before that, 4:00 pm every day I would go to a nearby school. So I went through stages sometimes for several years I used to go to a school that was only for Qur'an. It was an evening school, an everyday evening school. They would only teach Qur'an there. Like it was a huge school, twenty classrooms, 20 sheiks, and each sheik had about 20 students. So I was part of those classes for about six or seven years. For those six or seven years, I memorized about half of the Qur'an or a little bit less. (Soysal 2016)

Suleiman eventually was able to memorize the entire Qur'an by the age of 13. For him, the fact that the text was already in his native language, helped him to memorize the text. For the children learning to recite the Qur'an in Baton Rouge, they have a new language they need to conquer as well as trying to memorize a complex and long text. Their teacher, Hanif Soysal, stressed the importance of knowing what it is that you are memorizing. "I'm not a hafiz, someone who has memorized the entire Qur'an, by far," said Hanif. "But for me, when memorizing, I memorize specifically. . . . I'm not going in any specific order, but I like to memorize those verses that spiritually mean more to me. And because they do that and because I know that they mean, it's much easier to have them memorized. It's helpful." (Soyal 2016)

Another teacher at the Masjid Al-Rahman, Nafes Hakim-Khiry Furqan is an American raised in the Islamic tradition. He echoed much of the opinions of Hanif and Suleiman about learning how to recite and then memorize the Qur'an. In our conversation, Nafes reminded us that learning to recite the Qur'an is not just for the sake of learning the text. The recitations have a specific role during one of the most important moments of the Islamic year. As Nafes comments:

We're encouraged throughout the year to recite from the Qur'an so that we won't forget it. Or so that we won't . . . our skills won't deteriorate. And it's like with anything. If a singer doesn't sing for a while, they have to take more time to rehearse before they do it. . . . If you stay out for a while, you'll have to take a long time to warm up before you are good at it. So anything that involves recitation memory, muscle memory. It's encouraged to practice that throughout your life. Even if it's just thirty minutes a day, so that you won't forget it or get worse at it. But we do have a set time of the year when it's really important, we get out as much as I can, as much as we can and that's during Ramadan. The month where we fast.

Ramadan is the holy month in the Islamic calendar which celebrates when the Qur'an was first revealed to the Prophet Mohammed. During the month of Ramadan, followers fast during the day for thirty days, and break the fast at the end of the month with a celebratory feast called Eid al-Fitr. Not only is the Qur'an essential to the celebration of Ramadan, its structure reflects its use during the month. The Qur'an is divided into 30 sections, called juz'. These 30 juz' allow for the Qur'an to be recited daily within a month's time. According to Dr. Soysal, Ramadan is a time of training the self, and practicing the recitation of the Qur'an aids in this training. He adds:

But on the other hand, Qur'an itself, we call it the shifa, healing for hearts. It heals the hearts. We cannot say that it heals like medicine, it heals your spirit. That's why Ramadan also when we increase the reading the Qur'an the way it is supposed to be heals our spirit. Also so we learn how to control ourselves and we heal ourselves. We take care of ourselves spiritually reciting the Qur'an. (Soysal 2016)

Greek Orthodox Chant

In the Greek Orthodox community, recitation of holy texts and prayers takes on more musical connotations in their liturgies. The Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church in Baton Rouge is very small, but they have a devoted and active community of congregants. On a typical Sunday, two or three chanters are at the front of the church near the altar leading the service and the congregation in what sounds like ancient prayers. And as Father Anthony Monteleone, the leader of the church, commented, the chants are ancient in both their texts and their melodies:

In Orthodox spirituality and tradition, the liturgy is literally making heaven present on earth. It is literally the union of heaven and earth. And what plays a very important part in this experience is the chant. . . . Music, chant, on one hand, it transforms prayer. It transform prayer into song, and that song transports us from earth into heaven or heaven unto earth. With Orthodox being mystical and practical, once it's over, you go out and do what you got to do. But you carry that song in your heart which has been chanted as we hear it with roots two thousand years old. (Monteleone 2016)

Because chant is so central to the liturgy, the Greek Orthodox calendar is even shaped by chant. Each week of the liturgical year is marked with a tone, which is the initial tone for all the chants in the liturgy that week. During specific liturgical seasons, such as Lent, the tone's sound will reflect the mood and meaning of the season. There are eight tones in total which are cycled in succession through the year. Father Anthony related the tones to the ancient Greek tones described by Plato in the Republic. These tones can evoke a different mood and express or underline meanings found in the texts being chanted. In total, the tones and the liturgy all revolve around the Easter liturgy and the theme of Resurrection, which Father Anthony described as "the liturgy of all liturgies." He explained by reading a hymn that would be recited in the Fourth Tone:

The content, the meaning in English. 'The joyful news of your resurrection was told to the women and disciples of the Lord by the angel. Having thrown off the ancestral curse and boastingly told the apostles, Death has been vanquished. Christ our God has risen, bringing to the world great mercy.' You have in this hymn, in a nutshell, Eastern Christian Greek Orthodox worship. Because at the heart of our worship is the celebration of the Resurrection. . . . So consequently, the traditions in the Eastern Orthodox Church in the liturgy itself every Sunday, emphasize, emphasize, emphasize the joy and even the triumph in the joy of the Resurrection. Not only in the world to come, but in the world now. . . . This is the hymn sung in Greek in the fourth tone. And you may note it should indicate a mixture of joy and triumph together, which is Resurrection. (Monteleone 2016)

On a recent Sunday at Holy Trinity, a group of three chanters led the congregation in celebrating, Orthodox Sunday, the first Sunday of Lent in the Orthodox calendar. The chanters sang for almost the entire two hour service. Their role is to lead the congregation in the singing of the liturgy, chanting the prayers, litanies, and responsorial hymns. As Jaycob Warful, a chanter at Holy Trinity noted:

There's really nothing that we sing that is off-limits for the congregation to sing and ideally we could have as many people singing as possible. It's been estimated in many different places that the liturgy is made up of 4/5ths of hymns. And all of those hymns should be sung by the entire congregation. But all of those hymns, as we are discussing with the litanies, the responses, those things are very repetitive specifically to encourage more people to engage because the more familiar they are with them, the more likely they are to engage. (Lacraru and Warful 2016)

There are hymns or special songs that the chanters will chant during some liturgies, and during these times, the chanters are usually the sole singers, only because the congregation may be less familiar with the hymns being lead. Noticeable during many hymns is the way in which the chanters sing. One chanter may take the melody line, which the congregation may also sing, while another chanter will sound a drone note underneath. This drone note, called the ison, is sung by the lead chanter and helps to keep the congregation and the other chanters within the range of the musical mode for the chant.

When asked how the chanters learn to sing, the answers reflect the nature of life as a musician in a small community, and in the age of technology. Most members of the congregation at Holy Trinity have grown up with the tradition, and as Father Anthony observed, "if you want to know what the faith is of the Orthodox Church, apart from the scriptures and the New Testament, you don't have to study great books of theology. You just have to study and know the chants." (Monteleone 2016). Both Emma Lacraru and Jaycob, chanters at Holy Trinity, grew up within Orthodox communities and learned through attending services. Other resources include seminars and workshops taught by the Archdiocese in Atlanta, and online essays on the Archdiocese's website. Emma noted that in her native Romania, the conservatory where she studied even had a special section where musicians could specialize in Byzantine music in all its complexity.

Each Greek Orthodox Church also has a special hymn that is attached to that particular church. It is sung at nearly every liturgy, and will relate to the name of the church, whether that is a saint's name, or Patriarch or one of the three holy hierarchs. For Holy Trinity, their song is a hymn of Pentecost. And while chant is essentially meant to be a congregational hymn, the role of the chanters is still an important position within the service, as Jaycob pointed out:

Most of the service is composed of the hymns, so the chanter is going to be the primary individual responsible for doing that, and historically it's been an office that people are appointed to and ordained to, almost the lowest level of ordination through which individuals would go who were rising up through the ranks by their chanter and then maybe deacon, then priest and so for. So it is a very important position because it really keeps the rest of the congregation on track, as I has said, with the part that they meant to play. Once again, reiterating that ideally everyone would be singing but the chanter is the one who is meant to lead them in that singing, so yes, it's very important. (Lacraru and Warful 2016)

The appointing of chanters in this small church is done by recruiting strong singers from the congregation. That is how it happened for both Jaycob and Emma. An elder chanter at Holy Trinity heard Jaycob singing in the pews, and asked him to join the chanters. In turn, Jaycob recruited Emma to chant because of her strong musical background. By leading the congregation in prayer, chanters in the Greek Orthodox Church celebrate and nurture a tradition that is thousands of years old, as well as help to build a new and growing community here.

Vietnamese Buddhist Chant

Another community with an equally ancient tradition of chant is the Vietnamese Buddhist community in Baton Rouge. Like with the Greek Orthodox Church, the Buddhist traditional liturgy involves an almost seamless flow of chant throughout the service. The congregation participates in the service by chanting, bowing, praying silently, and listening attentively to the priest during the Dharma talk. In Baton Rouge, a large community of Vietnamese Buddhist worshipers attend the Tam Bao Meditation Temple, where the practice is focused on a Zen Buddhist tradition. While the majority of those who attend the temple are Vietnamese, there are also many Westerners who are able to follow the liturgy through the aid of translation via wireless headphones. Another member of the congregation simultaneously translates the service for those without the Vietnamese language.

The temple is located within a large compound, beautifully landscaped with flowering plants and trees, and situated alongside a courtyard shaded by large live oak trees, from which hang large metal wind chimes. After a Sunday service, the congregation gathers in the courtyard to eat a vegetarian lunch and visit with the monks at the temple. The atmosphere on a Sunday is warm and welcoming. The congregation, also known as the sanga, meets at various times in smaller groups throughout the week, but just like other religious institutions in Baton Rouge, Sunday morning is dedicated to the largest gathering of those who attend the temple each week.

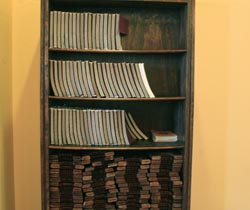

Before the service, members will slowly take their place on the floor, sitting on a round cushion and placed before them, a wooden book holder on which are two books containing the chants, songs and order of service for the temple. The liturgy begins with the ringing of a large bell right outside the door to the temple, alerting stragglers that the service is soon to start. A group of chanters, dressed in grey robes, sit at the front of the temple facing the congregation, and begin a series of chants. The title and page number of the chant is announced, usually in Vietnamese and sometimes in English, and the congregation is encouraged to sing along.

Behind the chanters is the altar space where the Abbot sits, and behind the abbot is a large stone statue of the Buddha. On either side of the altar are two instruments that are played by a designated chanter at specific times during the service. One is a large brass bowl, the chong gia tri that acts like a bell and is both struck and dampened on its rim. It is used to highlight specific moments when the congregation changes to a new chant or shifts to a new part of the ceremony. The second instrument used in the service is a large wooden drum, which is shaped like a fish. One of the chanters will use a large mallet to strike the drum on its dome-like top, usually during the recitation of sutras. The drum is used in a portion of the service when chanting takes on a very deliberate speed, with the drum inciting a faster rhythm to the chant. Before the service begins, however, the speed is slower, and the chants are each led by different members of the chanting group facing the congregation.

Thich Dao Quang, the Abbot of the Tam Bao Temple, explained that the service structure for a typical Sunday as such:

Usually, this is our life, the structure of the Sunday service. I start at 11:30 am Louisiana time. I like to be on time, by inviting the whole sanga, the whole community to sit down and quiet their mind within 10 minutes. And then stand up, we prostration three times. We show love and respect to the Buddha, Dharma and Sanga. Buddha the founder of Buddhism. Dharma, his teaching, teaching of love and compassion. And Sanga, the community in which everyone practice living in peace and happiness. Then, depends, for example, beginning a new service or repentance service, so the chanting is emphasizing about everyone makes mistakes but then everyone has potential to learn lessons from his or her mistakes and move on and make their life better, . . . And also following fifteen minutes chanting maximum, then I prepare a short lesson or sermon you call, or dharma talk within 40 minutes. And the themes of every Sunday depends on what's going on. It's not about what I like to teach but what's going on in the community. And I think that is the most appropriate topic for the community. For example, on this Sunday, I have a thought to offer for the dharma talk, "How to transform the negative karma into positive karma." And following the service, after the dharma talk, people stay together, enjoy the community lunch and do the community work. I see that this is the best way to enrich the brotherhood and sisterhood of the community. So that is the typical service on Sunday. (Quang 2016)

As the Abbot explains, the chanting during the service has a direct connection to the topic of that day's lesson and also to the general teachings of Buddhism. The basis of the chanting comes from different main texts within the religion, which are called sutras. These are the teachings of the Buddha and are chanted during specific times within the service. The sutras are known by names like the Heart sutra, the Lotus sutra, and the Diamond sutra. For the Abbot, he chooses a sutra for the service that will fit with the main theme he will be reflecting upon during the service. Another chant present in the service are mantras, which are short sequences of chant that are recited to encourage meditation. Mindfulness is an important part of the practice and chanting is used as a tool for gaining "bright attention." The Abbot, in particular, mentioned that there is a structure to chant which aids in the attainment of mindfulness. Quang explained it this way:

Phase One, or Part One, you may say that, you're accepting your weaknesses. Second part, this is understanding the weaknesses, if you're not transformed, create more weaknesses in your life, in the community, in the society. So the second part is promises to transform your negative behavior, actions and so forth. The third part is that you believe in yourself. That you have a self confidence that you can do it. You can transform it and then you promise you can contribute back and help the community. That's the powers in all the chanting here I pick. And sometimes I emphasize on the concept of compassion, so all the chanting is become compassion with yourself, compassion with the others, and compassion with all things in your life so that you can get more benefit and also create the good merit.

Chant also has a function outside of the temple service, especially as it is used as a tool for creating good merit. Brother Fred Van, a young monk at the Temple, explained that chanting gives you positive energy and helps you keep mindful in situations outside the temple walls. The important focus is not on memorizing words and reciting them in a mechanical way, but instead a focus on the meaning of the words will bring centeredness and reflection to aid in any situation. As Brother Fred shared:

When you chant with your whole heart, just like singing a song and you understand what the music means and you put your whole heart into it, and the meaning of what you are chanting, like what I just went through, invoking the name of Buddha. If you understand when you are chanting deeply and are full of peace, full of love and full of energy, it brings, it nourish the wholesomeness, that good seed in yourself. It's like, yes I have the ability and today I'm going to conduct my life in that way. It's just a reminder. And when we are going through difficulties in our life, those chants, those evoking certain mantras or certain gathas, it helps remind us, "Ok, let's come back to my breathing. Let's come to my understanding and have compassion for this person." And we do that daily, just like music. If you could just sing that one song that connects with you and awakens you in that moment. (Van 2016)

While the chant helps to awaken the chanter through the words of the chant, the language of the chant can be an impediment, not only in the style of the language but also the terminology. At the Tam Bao Meditation Temple, Modern Vietnamese is the main language used by the sanga. However, many of the original religious texts, the mantras and the gathas (verses used to help breathing in meditation), used more ancient forms of the language. According to the Abbot, these ancient languages are an impediment to understanding for a modern congregation. But the adaptations he makes in the texts not only focus on the language, but also on the content. He shared an example of Buddhist monks who cited the holy River Ganges in India as a specific symbol. The Abbot felt that the resonance of the example would be lost with such a foreign and unknown river used as the important metaphor. His solution was to make the example closer to home, "But how many people here know about the Ganges River? So I just say Mississippi River--that is the language I may prefer." By making these kind of adaptations, the tradition is allowed to continue with resonances that connect the congregation to the lived reality of their everyday lives.

Chanting takes place within other services at the temple, including a special gathering that is called the Forty-Nine day service. At Tam Bao temple, this service is celebrated 49 days following the death of a member of the congregation. That member's family will request the service in order to show respect and love to the spirit of their loved one in the wake of their passing. Quang considers the Forty-Nine day service to be a important part of the grieving process and a way to "transform negative emotions." The family, along with the monks, will meet at a section of the temple dedicated to the ancestors, prior to the Sunday service. The service includes a short period of chanting, during which time the family reflects on their deceased family member. Then, the family will join the sanga for the usual Sunday service, which, in a way, allows them to knit themselves back into the fabric of the congregation. Again, the chant in the different services acts as prayer and the prayer brings attention and mindfulness both to the individual and the community.

In all of these conversations about chant and recitation, the use of the term "music" seemed a clumsy way to talk about sacred language and sacred sounds. In Islamic tradition, there is a complete division between music and recitation. Music is secular, while recitation is sacred. There are musical elements in recitation, but these elements are not conceived of as musical by those who recite. Likewise, in the Buddhist tradition, musical elements are part of the experience of chanting, but chant is not considered to be music. The Abbot at Tam Bao temple reflected on the issue:

When we borrow the language, when we say chanting, different people come from different culture, background, they may have a different perception. But from my personal experience, I can see that chanting is the spiritual food. We need it. Even I practice by myself. I feel that I have a more positive energy after I practice seated meditation and short chanting in the morning. [It] promotes me, motivates me to overcome all obstacles in life. It motivates me to continue my dissertation research! So for me, if you truly understand the language of chanting, that's the powerful spiritual tool you should carry even when you stuck in traffic. Instead of worry, [it is a] great opportunity to chant.