Table of Contents

Folk Regions

Three Ethnic Perspectives

Folk Music of the Florida Parishes

People of the Florida Parishes

In Retrospect

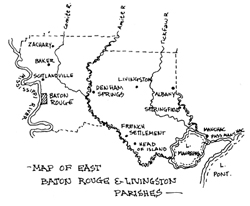

East Baton Rouge and Livingston Parishes

By Joyce M. Jackson and Maida Owens

Linking East Baton Rouge and Livingston parishes is awkward, despite the fact that the two are the closest of neighbors. East Baton Rouge, however, is predominantly urban, comprising many diverse ethnic groups, and Livingston Parish, mostly rural, seems more a microcosm of Louisiana itself: Anglo-Scotch-Irish north of U.S. 190, and culturally heterogenous to the south of that highway.

The original inhabitants of Baton Rouge and probably Livingston were the Houmas Indians, who were driven south by the Tunicas in the early 1700s, but little remains of the Indian culture other than material artifacts and place-name. Culturally, any Indian folklife is a recent reintroduction or revival.

Baton Rouge was first settled in 1763 as a British military outpost, and remained culturally British American, even during Spanish rule from 1779 to 1810. Although Indian trading posts and hunters had been along the Amite and Natalbany Rivers since the mid-1700s, the first communities did not appear until late in the eighteenth century. These communities depended upon the rivers for transportation and focused on the swamp occupations and farming. Springfield, on the Natalbany River, was settled some time before 1800 by Americans. French is rarely spoken in Springfield. Port Vincent, on the other hand, was French speaking, even though it absorbed many Germans, Spanish, and Canary Islanders. A group of Acadians arrived in French Settlement in 1810, but other ethnic groups also settled there. The northern half of Livingston was only sparsely settled until the mid-1880s.

Gates, a small community between Denham Springs and Port Vincent, saw the intermingling of the French Catholics and the "American" Protestants. Marriages between the Anglos and French were common from early on, so that most families include both Protestants and Catholics. The same mixture was true with the languages. Both French and English were spoken in homes, and many individuals were bilingual. Occasionally, a spouse would learn the other language after marriage.

By the early 1800s, several ethnic groups lived in Baton Rouge: Anglo Scotch Irish, Spanish, Canary Islanders, French, and a few Blacks. In addition to the small town of Baton Rouge, the parish contained several smaller farming communities. The area south of Highland Road was farmed by Germans from Pennsylvania known as the Dutch Highlanders. To the north and east of Baton Rouge were farming communities of Anglo-Scotch-Irish--Baker, Zachary, the Plains, and Greenwell Springs—that depended on cotton farming. When the boll weevil destroyed the cotton crop in 1905, many farmers switched to dairy cattle and livestock. Dairy farming remains prevalent in the northern part of East Baton Rouge Parish.

Before the Civil War, both Baton Rouge and Livingston had small Black populations. This still applies to Livingston, but Baton Rouge has become more racially balanced. During Reconstruction, Blacks migrated from plantations to Baton Rouge, establishing a sizable community in Catfish Town along the Mississippi River. By 1880, Baton Rouge was 59 percent Black, but this percentage dropped to 39 percent by 1920 with the absorption of other ethnic groups.

During the late 1800s, Louisiana actively encouraged the migration of farm workers through national recruiting and advertisements. Officials preferred farm workers of northern European ancestry from nearby states and were often frustrated when the diverse ethnic groups did not want to stay on the plantations. Italians came in large numbers during this time, but many bought farms or moved into the towns and set up their own businesses. Louisiana differs from other parts of the United States in that its Italian population is nearly all Sicilian.

During the late 1880s and early 1900s, logging was greatly expanded, and Livingston Parish enjoyed an economic boom. Logging had existed on a small scale since early settlement, but now large companies moved into Livingston, cutting virgin pine in the north and cypress in the south. Towns such as Holden, Doyle, Livingston, and Walker began as logging camps. Reforestation was not attempted by the large companies, and the land was sold. In many cases the cleared plots became truck farms.

Harris McCullough moved to the town of Livingston in 1920 to work for Lyons Lumber Company as conductor on a log train. By 1931 Lyons finished cutting all the pine and closed down its operations. Harris McCullough recalls, "I was raised on a cotton farm up in Mississippi. I knew how to make a living out of the ground. So when the job cut out . . . and the Depression hit, I went and bought me a pair of good mules. [I] had a few cows at the time and the cattle kept building and building. . . . I used to kill fifteen, twenty hogs every winter. I'd make sausage and fifty pound cans of lard. . . . How could you starve a man to death doing that?" The McCulloughs also had chickens and fig, pear, and persimmon trees, in addition to their truck farm. Firewood came from the nearby forest, while blackberries, mayhaws, and mushrooms grew in the fields. McCullough would occasionally sell a calf if the family needed cash, though store purchases were limited to flour, sugar, coffee, and rice.

The major ethnic groups in Livingston Parish are English, Irish, German, French, and Blacks. A group of Hungarians purchased some of the cut timberland near Albany in 1896. Their relatives joined them and formed the community of Hungarian Settlement. (See Hungarian Folklife in the Florida Parishes of Louisiana.)

In 1909, a hurricane blew down most of the white oak trees in Livingston. The Lewis Werner Barrel and Stave Company sent in work crews to make staves from the felled wood. These work gangs were predominantly Slavic, and several of these men married local women. These families moved on with the company traveling from one job site to the next. The company folded when Prohibition cut the demand for whiskey barrels, whereupon many men who had married Livingston women returned there to live.

The early 1900s marked an economic turning point for Baton Rouge. In 1909, Standard Oil, now Exxon, located a refinery north of Baton Rouge. The local economy grew increasingly stronger even during the Depression. The petrochemical industry became a major employer in Baton Rouge, and large numbers of workers flooded into the city for jobs. From farms and small towns in both Louisiana and nearby states came unskilled and semiskilled workers, both Black and white. From further states came the skilled workers and professionals of diverse ethnic backgrounds. Communities to the north of Baton Rouge, such as Baker and Zachary, flourished because workers could take the train to the industrial plants.

Today, the petrochemical industry, two universities, and state government provide the city's core of employment. Livingston also benefitted from Baton Rouge's growth, since, with improved roads, it attracted many commuters. Some were able to maintain a balance between folk trades and income from a mainstream job.

During and after World War II, the Baton Rouge economy boomed. The chemical industry expanded, and retail, construction, and services followed suit. The continued migration of workers from small towns and farms brought many different ethnic groups to Baton Rouge; this latest wave included Cajuns.

As Baton Rouge developed, ethnic groups did not cluster in homogeneous neighborhoods. Settlement was based on economic stratification, not ethnicity. Thus, Italians, Cajuns, Anglos, Orientals, and others lived side by side within a neighborhood.

The one exception to such ethnic mixing is the Black community, which has largely stayed segregated in three areas: Eden Park, Scotlandville, and the area between Louisiana State University and downtown.

The major ethnic groups in Baton Rouge are the Anglo Scots-Irish, Cajuns, Italians, and Blacks. The 1980 census records large numbers of Germans and Irish, but for the most part they have assimilated into the larger American culture. Many other groups live in Baton Rouge in smaller numbers. The Indians and the early settlers of Baton Rouge (French, Spanish, and Acadians) have blended into the larger culture and do not remain ethnically distinct. The 1980 Census lists considerable numbers of American Indians, Asian Indians, Mexicans, Cubans, Chinese, and Vietnamese. Almost 98,000 people in Baton Rouge list their ancestry as other than the fifteen major groups recorded by the census. Many may be foreign students at Louisiana State University or Southern University who are temporary residents. Others may be instructors or graduates who have taken jobs in Baton Rouge and have joined the community.

The majority of Blacks who live in Baton Rouge today have personal roots or family ties in surrounding rural towns such as Zachary, Denham Springs, Pride, Port Hudson, Baywood, and Greenwell Springs. These were, and still are, areas of intense concentration of Black folk tradition, because the majority of the families were basically self-sufficient.

The past fifty years have witnessed a massive migration of rural Blacks to urban Baton Rouge. Going back only as far as 1960, there were 29.9 percent Blacks in the city, which at that time had a land area of 31 square miles. In 1980 there were 36.39 percent Blacks in the city, which had increased to a land area of 61.6 square miles.

Blacks first moved from rural areas to find employment as industrial or domestic workers, or to continue their education. For example, forty years ago in the Zachary, Pride, Greenwell Springs, Baywood, and Deerford areas the only high school that Blacks could attend was Cheneyville High School, which is now Northeast High, and it only went to the tenth grade. So if Blacks wanted a better education, they had to travel to Baton Rouge to complete high school, and then perhaps go on to college.

After obtaining an education or a successful job, some families opted to return to the rural areas and commute every day to work. When several families were asked why they decided to move back to "the country," some of their reasons were as follows: they loved the serenity, there was less crime, they could have large vegetable gardens and raise farm animals, land was cheaper, it was a better environment for raising children, and they liked to hunt and fish. Therefore, many of their reasons for reverse migration were to "get back to basics" and practice the folklife traditions, which were difficult to do in the city.

Those who decided to remain in urban Baton Rouge settled in such areas as Zion City, Bird Station, Eden Park, the Lake, Easy Town, the Bottom, and Scotlandville (also known as "the field," "the avenues," and "the sticks"). These families make frequent trips to the country to visit family and friends and attend funerals, weddings, baptisms, family reunions, and other community gatherings. During these visits, many traditions are constantly reinfused from the relatives and friends who still live in the rural areas. One such reinfusion is the continuing link between the Black folk community and the religious practices of local Black churches, discussed in Music of the Black Churches.

Bibliography and Archival Resources

Berthelot, McCoy and Nora. Interview by Maida Owens Bergeron, French Settlement. March 29, 1984.

Carleton, Mark T. River Capital: An Illustrated History of Baton Rouge. Woodland Hills: Windson Publications, 1981.

Crnko, Gary. Interview by Maida Owens Bergeron, Livingston, March 29, 1984.

Dorman, James. "Striving for Success." A Better Life: Italian-Americans in South Louisiana. Edited by Joel Gardner. American-Italian Federation of the Southeast, 1983, p. 25.

Golden, Melvin, Sr. Killian. Interview, by Maida Owens Bergeron, March 30, 1984.

Harris, Joubert. Baton Rouge. Interview by Joyce M. Jackson, June 1, 1984.

Landry, Annette (Bootie). Baton Rouge. Interview by Maida Owens Bergeron, March 16, 1984.

Livingston Parish American Revolution Bicentennial Committee. The Free State: A History and Place-name Study of Livingston Parish. 1976.

Lollis, Flow. Baton Rouge. Interview by Joyce M. Jackson, April 23, 1984.

McCullough, Harris. Livingston. Interview by Maida Owens Bergeron, March 26, 1984.

McKowen, Chalmers. Lindsey. Interview by Maida Owens Bergeron, February 9, 1984.

Martinez, Leslie and Ruby. Springfield. Interview by Maida Owens Bergeron, March 30, 1984.

Salvaggio, Tony. Baton Rouge. Interview by Maida Owens Bergeron, Baton Rouge, February 16, 1984.

Shanabruch, Charles. "The Louisiana Immigration Movement 1891-1907: An Analysis of Efforts, Attitudes, and Opportunities." Louisiana History, 18 (1977): 213-218.

Shelton, Freddy. Gates. Interview by Maida Owens Bergeron, March 15, 1984.

Simeon, Maudie. Livingston. Interview by Maida Owens Bergeron, March 26, 1984.

U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census. "General Social and Economic Characteristics - Selected Ancestry Groups." United States Census of Population, 1980. Vol. 20-Louisiana, Table 60.

Wall, Allen "Dick." Springfield. Interview by Maida Owens Bergeron, March 30, 1984.

Wicker, Gladys. Zachary. Interview by Joyce M. Jackson, May 13, 1984.