Exporting Mardi Gras

By Barry Jean Ancelet

The traditional Mardi Gras runs of South Louisiana are powerful cultural expressions. The masking strategies, the striking costumes, the ceremonial songs and music, the intriguing begging rituals and intense play, the whippings, the chicken chases, all make for an impressive show. A number of studies have shown how these practices are determined by the communities in which they occur (e.g. Lindahl, Ancelet, David, Brassieur). Indeed, each community's Mardi Gras has its own look, its own moves, its own play, and its own sounds. Mardi Gras makes sense in its own place and in its own time. Take the same people operating with the same strategies on June 3rd and it doesn't work. Take the same people operating with the same strategies, even on Mardi Gras day, to Peoria, and it doesn't work. Mardi Gras is not only the interaction among participants, but also the interaction between participants and the people and places they visit. Hosting visitors from the outside is already a risky proposition. Tourists observing some of the more intense runs can be taken aback by the hard play, including whipping and wrestling within the group and sometimes with hosts and other observers, chasing and catching chickens, masking and costuming strategies based on caricatured gender and racial inversion, and irreverent and un-pc religious and political parodies. Taking this kind of hard play out of its ritual context and on the road is even riskier. Nevertheless, a number of people, myself included, have been tempted to take the traditional Mardi Gras out of its traditional time and place to exhibit it for other audiences. This has had mixed results, sometimes hilarious and even stunning, sometimes troubling. In all cases, there are underlying questions concerning the relative worth and legitimacy of such attempts at ritual displacement.

Efforts to transpose tradition necessarily bend typical notions of historically continuous authenticity. While there may an attempt to recreate the ritual in a manner that approximates an authentic experience (as in some of the holistic presentations that have been part of some national festivals, such as the Festival of American Folklife, the displacement of it necessarily can only produce a version that is at best “authentic-like” (Bendix 1997: e.g. 148 and 217) or what I have come to call faux-thentic. All such recreations must overcome logistical and conceptual challenges in order to exist at all in ways that are deemed at least functional by both participants and their potential hosts. This can and does produce unintended consequences, some of which can be illuminating or disturbing, but never authentic. This also exposes the difference between vernacular and expert understandings about how this complex tradition works. Inspired by ideas proposed by Charles Cantwell, Roger Abrahams, Frank Prochan, and Carl Lindahl, this paper will explore several attempts to take a Mardi Gras celebration out of its traditional context in order to present it to outside audiences, from the simple inviting of a traditional run from one town to a performance in a theater in a neighboring town during Mardi Gras weekend to the representation of multiple versions of the Mardi Gras during the Smithsonian's Festival of American Folklife in Washington, DC.

The Basile Mardi Gras at the Liberty Theater

My first example is the mildest one, the annual Basile Mardi Gras visit to the Liberty Theater in nearby Eunice during the weekly live radio show there on the Saturday before Mardi Gras. The City of Eunice itself is keenly aware of cultural tourism and its opportunities. In Mardi Gras terms alone, it has long welcomed any and all participation from outside the community. This has produced mixed results for the city and the traditional run it hosts. The thousands of tourists who come to Eunice each Mardi Gras season are accommodated with presentations on the tradition beforehand. Tourists can find masks and costumes in a number of stores in the community, feeding an annual cottage industry. The city produces a four-day Mardi Gras-oriented folk festival in its streets to provide the tourists with a satisfying cultural experience. Most tourists opt to stay in town, enjoying the music and food and welcoming the Mardi Gras as it returns from its run through the countryside in mid-afternoon. Many others, however, give in to the temptation to join the traditional run during the day. This has produced a seemingly endless cortege that is not only drastically over-inflated, but also diluted with hordes of participants who cannot be expected to provide appropriate Mardi Gras behavior.

It is in this context that the Basile Mardi Gras visit to the Liberty occurs. The Saturday night before Mardi Gras, the theater is filled to capacity with a mixture of locals and mostly tourists. The Basile group's own traditional ritual includes visiting bars and clubs in their community during the weeks before Mardi Gras in order to perform and raise money for their run by means of the ceremonial begging they routinely do during these visits. At the invitation of the Liberty's programmers, the Basile group travels outside of what most would consider their community to do the same singing and begging they do back home.

It's only fifteen miles, but in Mardi Gras terms, which are deeply rooted in community, it's nevertheless worlds apart. Yet they come, happy to have the opportunity to sing and strut their stuff in front of such a large audience. But when they start their Mardi Gras engine in order to demonstrate their cultural practice to this audience, they don't throttle back on any of its complex aspects, including authentically enthusiastic (even aggressive) begging. They are happy to perform for the audience, but they also fully intend to extract monetary donations, even if this invokes strategies that they have devised for running in their own community, such as (temporarily) stealing shoes or hats or anything else they can reach, hugging and even kidnapping spouses. This can be slightly disturbing even in its own natural context within Basile on Mardi Day. Tourists in the Liberty that Saturday night can find it truly puzzling and sometimes disturbing, unless there is a rush of reassuring commentary shouted over the din of the performance to explain what is happening. It is a bit like playing a game with rookies while explaining the rules. While the audience may enjoy the thrill, a little of that goes a long way, as one member once told me. But Mardi Gras behavior is all about disturbing and challenging social norms. So in recent years, association president Potic Ryder has genuinely struggled to contain the boisterous play of his charges, especially in convincing them to end the play. Precisely because the audience is wishing it would end, the Mardi Gras instinct to transgress encourages them to continue. The ultimate result is an audience that is at once dazzled by the experience and relieved to see it end.

The Basile Mardi Gras In Québec

In part because of their experience with exporting their performance as far as Eunice, I got the idea to involve the Basile Mardi Gras in a programming experiment when the Festival International des Arts Traditionnels de Québec was looking to include a Louisiana French component to their event in 1999. In an attempt to take into consideration issues that context-minded folklorists such as Frank Prochan and Charles Cantwell have addressed, calling for more holistic, community-based programming at folk festivals (Public Folklore 2007), I suggested they invite the Basile Mardi Gras as a group. Within this group, I suggested, they would have a cultural critical mass that would include culinary traditions (the communal gumbo), traditional music (the ritual song and the music that is played for dancing at the hosts' houses), and material culture (mask and costume making), as well as the performance of the ritual itself.

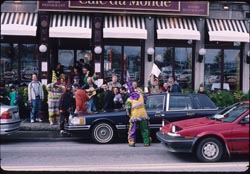

The festival organizers were eventually convinced to try this integrated presentation, rather than the more typical approach that would involve disparate bearers of various traditional arts. So the Basile group went to Québec where they demonstrated the various aspects of their Mardi Gras. Visitors could watch the masks being made and then try them on. They could watch the making of the gumbo and then taste it; they could listen to the music and dance to it. Then the Basile group was asked to put the whole affair together and demonstrate a run, which they were happy to do. They had demonstrated their tradition before at the Liberty Theater, as well as a few outings at the Louisiana Folklife Festival in several cities within the state. But the only real way to demonstrate a Mardi Gras run is to run Mardi Gras. It's the only way that the playful and subversive dynamic can be conjured (cf. Cantwell 1991; 1992). So they cranked up a performance in the museum.

Of course, Mardi Gras runs are not static; they move. The whole point is to visit and disturb/tickle what you determine to be your host community. So they headed out the back door, formed up in the park behind the museum and then headed out into the streets. They didn't have a clear idea where they were, but they instinctively improvised a route and headed down the sidewalk looking for the nearest bar, doing their ceremonial begging routines for passersby, who had no clue what this was about, Luckily, most seemed to figure out fairly quickly that this must be some festive performance associated with the nearby museum. Again, I was pressed into service to hastily explain to those they encountered what was going on. Some understood a bit and smiled, most had little or no idea how to take the performance and shied away from the group, clutching purses, bags and children. The museum and festival workers didn't know this would happen either, but were reluctant to restrain what they had after all asked the group to do. We were quite frankly all intrigued to watch this spontaneous carnivalesque improvisation. The group processed down the street, with a small entourage of handlers trying to buffer the public as much as possible. They finally made it to a bar, which should be familiar territory, and went inside. There, I was barely able to prepare the customers for what was about to happen. They asked for permission to perform, gathered together, sang their song, danced to the music provided by their accompanying musicians, and then genuinely begged for donations from everyone inside, including drinks from the bartender. Alerted to the situation and made aware that this was a spillover from the nearby Musée, everyone cooperated. And the group left happy.

But Mardi Gras is also about challenging thresholds, so once back out into the street, they escalated the stakes. Rightly assessing that they were in an urban setting and extended their ceremonial begging into the street. Then they gathered at a bus stop and waited for the next bus. I was able to convince Capitaine Ryder that this might not be a good idea, since neither of us knew the Québec City bus routes and how far the bus would take them. They toyed with the idea of boarding the bus anyway, mostly to make me nervous, but then they resumed their procession along the sidewalk and hit the next bar they saw. The experience from the first bar was virtually repeated. When they left again, I was able to convince the captain that this was just a demonstration run after all, and that we could head back to the museum now. He agreed and led his contingent back, but not without interacting with everyone they passed on the way. When they were safely back into the museum, they sang their song again, danced a bit more, and then served and ate the gumbo with all who were there, according to their tradition.

To the relief of the organizers, no one had been lost, or hurt or too offended, but it was definitely more Mardi Gras than they had anticipated. It was probably less than the participants would have happily done if given more rein. The group had extracted a truly Mardi Gras feeling out of this artificial experience by insisting on going out on their own terms, by ignoring efforts to deter them. Mardi Gras is about disturbing, inverting and subverting. They took their charge to generate nervous laughter very seriously. The folks on the street, in the bars, and on the bus had provided some of this, but the most successful nervous laughter they were looking for was from their hosts, and the only way to get it was to go out and thus make them and me nervous.

Mardi Gras at the Festival of American Folklife

Another example of improvising Mardi Gras in an artificial, out-of-time and out-of-place context occurred in the summer of 1985 when Louisiana was featured at its annual Festival of American Folklife. Along with Cajuns and Creoles, there were folk performers and craftspersons from all over Louisiana, including Mardi Gras float builders, Mardi Gras "Indians," second-line dancers and a jazz band from New Orleans. Participants and presenters came up with the idea to have these groups parade through the site to give the crowds something of a Mardi Gras experience. Festival organizers hesitantly agreed. We realized that doing this had great potential to attract festival goers from throughout the site so we timed it to start late in the afternoon, just before the rest of the festival would shut down and just before the scheduled dance party in the Louisiana section. As the improvised parade snaked its way through the site, it became clear that something larger than we anticipated was happening on its own. The parade moved outside the Louisiana area attracting crowds like a magnet. Soon there were thousands of people instinctively imitating street performers Pork Chop and Kidney Stew as they danced and marched a second line following the floats, the jazz band and the "Indians." Eventually the procession arrived at its planned destination, the Louisiana dance party stage. The jazz band and the "Indians" gave inspired performances before yielding the stage to Filé, a traditional Cajun band scheduled to perform that evening. Filé opened its dance party concert with the traditional Cajun Mardi Gras song as several participants and Louisiana staff members appeared in improvised traditional masks and costumes to lead the dancing. By then, the crowd was in a near frenzy. Festival director, Diana Parker came up to me and said with genuine concern in her voice, "We're very close to losing control here." She was right, but that was after all the point. I replied happily, "I know! It's great, isn't it?" To her credit, she immediately switched gears and joined in celebrating the apparent triumph of the moment. We had somehow conjured something that approached the improvised events, the crowd had gotten even closer to a genuine Mardi Gras experience than even the most hopeful of this affair's instigators could have imagined. It wasn't exactly authentic, but it was effective. Typical of carnivalesque inversion, it succeeded in disturbing and exhilarating in the same moment its community, its participants, and especially its containment structure. It was such a powerful imitation of Mardi Gras that it was not repeated during the rest of the time we were there. And this may be just as well. Instigators of this plan found the experience exhilarating, but also found ourselves wondering about the wisdom of turning on such a potentially powerful cultural mechanism in such a foreign context. The potential for losing control was an important part of the issue, but we had not fully thought out the consequences of actually losing control. Nor had we fully thought out the social and cultural implications of conjuring Mardi Gras out of time and out of place.

Mardi Gras In Nova Scotia

A final example of improvising Mardi Gras outside of its time and place is from the annual Festival Acadien along the Baie Sainte-Marie in the Acadian region of southwestern Nova Scotia. Students of all ages, from mid-teens to late middle-age, have participated in the Université Sainte-Anne's summer French immersion programs at least since the early 1990s. During the five-week program, the region's annual Festival Acadien takes place in and around Pointe d'Eglise including the university campus. The festival features a parade down the Chemin du Roi, Provincial Route 1. Members of the community who have developed an affective relationship with Louisiana's Cajuns, mostly through the music, developed a Louisiana float for this parade. The immersion program began featuring a Soiree Louisianaise, with traditional music and food. It was only a matter of time before some participants began taking along Mardi Gras costumes and masks to enhance the Louisiana presence. Once so equipped, it was again only a matter of time before some got the idea to participate on the community's Louisiana float, dressing in masks and costumes and throwing beads, as per the urban carnival tradition. This was already a remarkable departure from the otherwise pretty staid floats of the parade. However, some of the Louisiana participants were from the rural Mardi Gras and began to perform in ways that derived from that source, which involved leaving the float and interacting with members of the community. They ran into the yards, mildly teasing homeowners and others who lined the parade route. At first, their Acadian cousins, who had no experience with such carnivalesque behavior, were a bit taken aback. They didn't know how to take the disturbances. Even the most tentative play, begging for personal items and dancing with their momentary hosts, was apparently very disturbing to those who had no experience with it. It was especially effective when the masked participants recognized members of the community with whom they had interacted. Masks have proved to be a major cultural threshold. The Acadians of southwestern Nova Scotia do not have a masking tradition, beyond the imported Halloween celebration for children. One of the most effectively disturbing activities along the parade route was to simply converse from behind the mask, calling the names of their hosts and demonstrating familiarity, taking full advantage of their anonymity. When they divulged their identity at the end of the brief improvised visits, there were invariably expressions of simultaneous relief and hilarity. The parade context opened the door just enough to admit a fleeting Mardi Gras-like experience, but there is much left to be negotiated between these reunited sibling cultures.

In recent years, this same Acadian community has begun to celebrate a tintamarre as part of its annual festival. This noise-making procession through the community, a cousin to the traditional charivari, was revived as part of the increasing interest in the public expression of Acadian solidarity since the first Congrès Mondial Acadien in 1994. In the Baie Sainte-Marie region, the tintamarre, characterized by banging pots and pans, whistles, horns and any number of other improvised noise making, has turned into an alternative parade complete with large caricatured figures and ingenious improvisations of the Acadian flag design. Again, Louisiana immersion participants and other Cajun visitors recognized the festive processional and community-affirming nature of this celebration and began improvising ways to join the parade in Louisiana terms, which have included waving South Louisiana Acadian flags and wearing colorful clothing that approaches costumes. Individual masks have yet to come up, but some of the larger than life caricatured figures would seem to indicate a potential for development in this area. The rate of improvisation will likely be dependant on the number of visitors from South Louisiana. And in the event that there is some infiltration, the extent to which this community-affirming procession is co-opted by Cajuns with Mardi Gras intentions will likely be mitigated by local sensibilities and expectations. Conversely, recent attempts to import the tintamarre to South Louisiana (e.g. at the Scott Cajun Heritage Festival) have proved awkward. Cajuns and Creoles know how to perform Mardi Gras, but the tintamarre, which so motivates their cousins from the North, representing their emergence from hiding after the exile of 1755, shows the signs of clumsy grafting.

Conclusion

Masked/costumed begging and performing processions are an enduring cultural expression of community solidarity throughout the French North American archipelago, from the Guillannée in Québec and the historically French communities along the Mississippi River in Missouri and Illinois to the Chandeleur in Prince Edward Island to the Mi-Carâme in Cape Breton to the Mardi Gras in Louisiana. But each of these ritual celebrations has its own character and meaning, shaped by the communities they affirm. Attempts to export these celebrations have produced some interesting, amusing and even informative results, but they remain at least somewhat problematic, precisely because they are so deeply rooted in their own liminal times and places.

Works Cited

Ancelet, Barry Jean. 1999. "We Love Our Mardi Gras: The Social Implications of the Mardi Gras and How We Read It," American Folklore Society.

Baron, Robert, and Nicholas Spitzer, ed. 1992. Public Folklore. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Bendix, Regina. 1997. In Search of Authenticity: The Formation of Folklore Studies. Madison: U of Wisconsin Press.

Brassieur, Charles Ray. 2002. "Mardi Gras Route Morphology and Neighborhood Configuration," paper presented at the American Anthropological Association (New Orleans).

Cantwell, Robert. 1992. "Feasts of Unnaming: Folk Festivals and the Representation of Folklife," in Robert Baron and Nicholas Spitzer, eds., Pubic Folklore. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Cantwell, Robert. 1991. "Conjuring Culture: Ideology and Magic in the Festival of American Folklife," Journal of American Folklore 104 (412): 148-63.

David, Dana. 1998. "De-Carnivalised Laughter in the Tee-Mamou Run," paper presented at the American Folklore Society annual meeting.

_________. 1999. Personal communication.

Lindahl, Carl. 1998. "One Family's Mardi Gras: The Moreaus of Basile." Louisiana Cultural Vistas 9/3: 46-53.

__________. 1996a. "The Presence of the Past in the Cajun Country Mardi Gras." Journal of Folklore Research 33: 101-129.

Lindahl, Carl,and Carolyn Ware. 1997. Cajun Mardi Gras Masks. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Sawin, Patricia. 2001. "Transparent Masks: The Ideology and Practice of Disguise in Contemporary Cajun Mardi Gras." Journal of American Folklore 114.452 (2001): 175-203.

Ware, Carolyn. 2001. "Anything to Act Crazy: Cajun Women and Mardi Gras Disguise." Journal of American Folklore 114.452 (2001) : 225-47.