Introduction to Delta Pieces: Northeast Louisiana Folklife

Map: Cultural Micro-Regions of the Delta, Northeast Louisiana

The Louisiana Delta: Land of Rivers

Ethnic Groups

Working in the Delta

Homemaking in the Delta

Worshiping in the Delta

Making Music in the Delta

Playing in the Delta

Telling Stories in the Delta

Delta Archival Materials

Bibliography

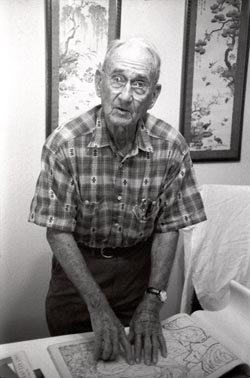

Oren Russell

Lake Providence, LA

Oren Russell worked on the Mississippi River as a tow boat captain and as captain of the Delta Queen steamboat.

Delta Folks - Oren Russell Mississippi River Boat Pilot

By Susan Roach

Born July 18, 1904, in Kilbourne, Louisiana, in West Carroll Parish, Oren Russell had a legendary 56-year career as an Army Corps of Engineers yacht captain, a tow boat pilot, and later captain of the Delta Queen steamboat on the Mississippi River. Living through floods and learning from older, experienced river men, he accumulated a vast knowledge of the Mississippi, which took him through an accident-free career and made him an expert on the greatest river in the U. S. Not only could he push a long "tow" of barges up the river, but also he could fearlessly maneuver his Airstream trailer through interstate traffic, even into his nineties. Captain Russell's river-related oral history, stories, and occupational lore provide a glimpse into the complexities of working on the river boats.

The Road to the River

While Russell's adult life was spent working river-related jobs, his youth was spent on a farm and then in a small town. His father farmed and had what was called a "groundhog sawmill"—a poor man's sawmill near Kilbourne, which was around ten miles from the Mississippi. Russell witnessed his first flood in 1912, when the Mississippi flooded the Arkansas and Louisiana side. His town of Kilbourne, located on the edge of Macon Ridge, did not flood, but his father brought the family down to lower ground to see the flooded land, as his story about it explains to a 1997 Smithsonian Folklife Festival audience:

My first introduction to high water was in 1912. I lived on the Macon Ridge. It's a ridge that goes down through Arkansas and Louisiana, and there's a flat place between the Macon Ridge and the Mississippi River, and in some places it's 10 to 12 to 15 miles wide; sometimes it's 20 miles, and some of it is not that wide. In 1912, I was a boy 8 years old, and my daddy was taking my family down to see the high water. Now the means of transportation back in them days . . . was a wagon with two horses pulling it, and we had 2 spring seats that the family—the women and the children—was on them spring seats, and I was standing in back of the wagon. And we went down the hill and there was that water upon the edge of the Macon Ridge; it must have been ten feet deep out on road where we used to go across going to the river with the wagon taking the . . . bales of cotton over to the river landing. (5 July 1997)

While this flood did not compromise the family farm that year, a few years later in 1921, Russell's father sold the farm, and the family moved a few miles north across the state border to Eudora, Arkansas. Russell tells the story of how in the next year, 1922, the Mississippi was high again and threatened to break the levee, and he, along with other young men, was conscripted to guard the levee on their side of the river:

The '22 high water was a big high water, and they conscripted the labor. I was conscripted, and the job that I had—they put me on a horse at night with a big pistol on me, and we would ride certain sections at the top of the levee. We was guarding against the people in Mississippi that might come over and dynamite the levee on our side to get relief for theirs. I assume that they were doing the same thing to keep us from on their side. But anyway, they gave me and all of us riders riding the top of the levee with no light orders that if anybody showed up out in the river coming toward the levee, if he didn't identify himself, we was supposed to shoot to kill him. And that scared me too. But the water was high enough right at the top of the levee that when the boats come down, the swells from the boat—the waves would go over the top of the levee under my horse's feet. (5 July 1997)

Fortunately, the levee did not break that year.

In Eudora, Russell's father got into the trucking business, which was just beginning in the region. The young Oren would go with his father to make deliveries of groceries from Eudora to Lake Providence, Louisiana, where they would pick up ice to take back to Arkansas. Because of his experience with the machinery in the family sawmill, Russell was offered a job in the ice plant—the only means of getting ice at that time, given that homes did not yet have refrigerators. Russell describes his work in the plant: "In the daytime, we'd run maybe a week and fill up the storage cold, storage room, with ice, three hundred pound blocks of ice. And then we shut down, and when we'd use it up down close to the end, we'd start back up and build it back up again. And that was the beginning of my working away from home" (16 May 1997). For two years, he continued the tough schedule, working 12-hour days and into the night, but he grew tired of it, so in 1925, he applied for and got a job as a truck driver for the Army Corps of Engineers.

For this job with the corps, he moved to Lake Providence to work for the general superintendent over the levee building project on the west bank of the Mississippi River, covering the territory from Pine Bluff, Arkansas to below Vicksburg, Mississippi. During the fall of 1926, Russell notes, "we knew the levee breaks were imminent because we had an awful, unusual amount of rainfall in that section of the country . . . all over the Mississippi valley, the Ohio valley, the upper Mississippi valley, the Arkansas valley" (3 July 1997). Breaks along rivers were occurring. Russell's supervisor moved their office from Lake Providence to Lake Village to be more centrally located to serve his area. As a consequence of the flooding, Russell recounts what the corps did when they received news of the levee break on the Arkansas River near Pendleton, Arkansas:

When the levee broke up on the Arkansas River, the engineering department knew that the whole west bank of the Mississippi River would be flooded to the Gulf, and they tried every means available to notify the people to go to higher ground, and there was a lot of people who didn't believe that the water would ever get there, and when it did get there, they had to go pick them up off the top of the roof. . . . But they were warned by every means available—paper, radios, word of mouth that the water was coming, . . . It was a devastating thing—all their animals on the Mississippi side and on the Louisiana side that was in that immediate flood wave. They lost all their mules, they lost all their horses, they lost all their cows, hogs, chickens—everything was drowned. It was a few of the people even got drowned because they didn't believe it. (5 July 1997)

Knowing that the Arkansas break would flood Lake Village, he asked Russell to drive the office furniture back to Lake Providence. He recalls when he got the news of the major levee break in April, 1927, at Mound's Landing near Greenville, Mississippi, that would actually provide some flood relief on the Louisiana side:

The morning that the levee broke before daylight, right around daylight, I had been out in my truck all night with 150 men working [on the levee] in that area, and if they needed something, it was my job to go get it and deliver it to the workers. And that morning—it rained that night like I'd never seen it rain, just downpours of rain, I went in at daylight to try to get a little rest, and sleep, and they come and woke me up at 9 o'clock—the district engineer had flown over the crevasse and come back down the river and dropped a message off that plane to the foreman of the levee machine that was building levees in that section. Of course, they weren't working then, but the camp was out on the bank of the lake and he dropped a white stocking with a message in it that the levee had broken at Mound's Landing [near Greenville, Mississippi], and that we should be getting relief in about 4 or 5 hours. And that's where I was. Actually, when it broke, I was on my way to that bed. (5 July 1997)

The break Russell references was the largest Mississippi River crevasse during the 1927 flood, and it did relieve the pressure of the water on the Louisiana side somewhat; however, other breaks on the Louisiana side and further north in Arkansas caused further flooding in the Louisiana Delta. According to Russell, people who did not flee before the flooding inundated the 27,000 square miles went to the levees, where they lived in army tents and were fed by the Red Cross for around 30 days before they could return to their land (3 July 1997).

As a consequence of the massive flooding, the Army Corps of Engineers began major work on building a strong levee for the next few years. Russell would work with the corps for 20 years, first as a truck driver and on to warehouse supervisor and finally river work.

In 1929, early on in his stint with the corps, he realized that the work on the Mississippi levee system in the region was nearing completion, and that his work with the corps might be coming to an end. One of his supervisors in the southern area, Jean Fife, invited him to go with him to visit with corps boat captain Harold Blue, who asked for a raise during their visit. On their way back, Russell said to him, "You know, I wouldn't mind having that job," to which Fife asked if he were joking (3 July 1997). Russell describes the job offer made to him later that week:

Mr. Fife called me up and he said, "Oren, Monday morning I want you to go down and check that boat over, take charge of it, and check all the property and go captain that boat."

I said, "Wait a minute, Mr. Fife, man, I don't know nothing about that river out there."

He said, "I'll leave Blue with you as long as you need him."

I said, "My God," to myself, I said, "Hell, I can't beat that with a stick. (16 May 1997)

Russell worked on that boat for a couple of years until it was condemned and replaced with a bigger one, which he was on for 9 more years. During that time, he had people from "every walk of life that . . . were hydraulic engineers or in hydraulics coming to Vicksburg. . . and they all wanted to take a trip on the Mississippi River to take a look at it. And that was my job to take them out and show them the Mississippi River" (3 July 1997).

Learning the River

Thus Russell would proceed to learn river piloting skills and knowledge of the Mississippi River itself in the folk process by working side-by-side with Harold Blue, a skilled river pilot. Russell worked with Captain Blue for the next three to four months. As he puts it, "I'd learned where the channel was, and where you could run and all the [river] bends and name of the bends and the lights." The complex system of river lights marked locations along the river; river vessels also had signal light configurations which had to be memorized. He learned the channel by sitting next to Blue at the steering wheel which controls the rudder in the back of the boat. They were in a small boat, a yacht, at that time, not a tow boat. Russell points out that pilots learned their jobs in a type of apprenticeship:

To learn the Mississippi River to become a pilot, you have to be a student; we classify them as a student. The teacher is that old pilot that has been piloting for maybe 40-50 years, and he's been through high water, medium stage, low stages, every stage of the river because the boat don't stop because the river's rising. You stand up there in the pilot house as a student and watch what he does and remember where you are on the river where he's doing that at because that's a critical point, and it don't go away. . . . You have to know the conditions of the river, what it's doing at that point. (28 June 1997)

His initial job consisted of taking corps officials on various jobs up and down the river. When his apprenticeship with Blue was over, Blue left to captain a tow boat, a job that Russell would take later in his career.

During his job as captain of the corps boats, from 1929-1943, he was trying to get his pilot's license. He had ridden in the pilot house with steam boat pilots who had even let him steer the big boats. The pilot's license required a year on deck and then a year in the pilot house as a "steerer" before one could apply for a second class pilot license. The examination for the license required detailed river knowledge, according to Russell:

You have to memorize every one of the names of every one of them lights, and associate them with the shape of the river, 'cause when you get up at midnight and it's dark, dark as night, so you see a little blinking light up there, a little white light up there above you, the pilot tells you, the man you're relieving, says, "That's Corregidor light." When he says, "Corregidor light," it sets off a memory up here [pointing to his head], you know where it is, and what the shape of the river is, and whether you are going up river or downstream. Which way is. You got to know that by memory. You got to put it on that map that you draw and put it—if it's got a gas line crossing the crossing, a high line across the top, some gas line up river—you got to put all that on it. You got to do that by memory because they got this man–one of the inspectors sitting right over there looking at you all this time you're taking the test. (16 May 1997)

He had taken the test in New Orleans, and it was sent to Memphis, but he had missed one light because a lighthouse had established a new light which he had not yet seen, so the inspector did not grant him the license at that time. He had to wait another year before he could come back and take the test, but he got his second-class pilot license on his second attempt. This license qualified him to pilot boats under 150 tons.

Russell gained his vast knowledge throughout his years of work on the river. He worked for two years on his first yacht until 1933 when it was condemned and sold, and the corps brought a big yacht to Vicksburg. Russell was selected as the new captain of that yacht. He worked that job for the next nine years until World War II on this larger diesel yacht, which was not different in operation, but was "bigger and nicer." The yacht's function was to chauffeur the corps' "big bosses" of the Mississippi River Commission and the district officials, as Russell recounts:

In Vicksburg they had hydraulic engineers from all over the world come to Vicksburg because they've got a big hydraulic lab. And . . . my job was when these prominent engineers would come to this country, they wanted to take a trip on the Mississippi River. And somebody out of the commission or the [Vicksburg] district would be with them and bring them on the boat. And I would have to take all of them out on the river for a trip. And the guy that was the boss, either out of the commission or the district would tell me how far up he wanted to go to show them stretches of the river. And some of them would be a day, just about a full day; some of them would be a half-day trip. (16 May 1997)

Living on the River Boats

Life on the river boats required the crew to be away from home for periods of time, so the boat was well equipped, and the captain and crew had regular duties. Russell describes the typical work and pay for the captain and his pilot: "There's only two of us and we work six on and six off, around the clock. . . . I got a hundred dollars a month more than he does because I had to keep the books on the boat and send in their daily reports and logs, and take down orders and put them in the office" (16 May 1997).

The typical crew on one of the corps boats had an all-white crew of 21, including a captain, the chief engineer, a first assistant, second assistant, two oilers (one for each shift), and under the cabin the head mate and second mate, who supervise the deck crew of eight deck hands. The rest of the crew included two cooks and two maids, whose job was to make the beds and clean the rooms for the officers. The women on the boat, who began working during World War II, had their own quarters which were off limits for the male crew. Russell says that having women on board did not usually cause any problems; however, he says, "I had to pay a couple to three maybe four maids off, because they'd get sweet on one of them little deck hands" (16 May 1997).

The captain directed all the crew, even told the cooks what to cook. Russell describes how he would direct the mate: "But the head mate was over the deck crew, and I'd tell him what I'd wanted and how I wanted the barges placed and go, and he'd put them in there and wire them up and have them so we could drop them over at the place" (16 May 1997). His first boat had two cabins, a parlor, and two engines. The captain was always on call, which resulted in lost sleep. Russell explains the importance of the role of captain:

When you running Captain you, you lose an awful lot of unnecessary sleep. . . . If there's any problem on the orders that this guy don't understand what to do, he'd come get you out of bed. Maybe you was asleep an hour or so; then it takes you a couple of hours to go back to sleep; [you] get to thinking about what's taking place. So as the captain, I've lost many, many hours o' sleep. . . . He [pilot] takes orders when I'm asleep on the radio, the message comes in for orders, he takes it down and writes it down, gives it to me when I come on the watch. But the difference in the steam boats and the diesel boats, the diesel boats are all controlled from the pilot house. And on the steam boats it controlled down in the engine room with this indicator. We tell what we want, and that's what we get. (16 May 1997)

When Russell was training to be a pilot, the river had no buoys measuring its depth and boats were not equipped with radar, so the depth of the river had to be "sounded," or measured, with a lead line by a deck hand, just as in the time of Samuel Clemens, who took his pen name, Mark Twain, from the sounding. Russell explains how this was done:

[It was a] long time before we had buoys after I started on the river. . . [Instead] we had a man with a lead line on each side of the tow (on the head of the tow) telling us how deep the water was with a lead line. It [the line] is marked off in one-foot intervals. It's got a color band around it, and every six foot, it's got a piece of leather. . . that's six-foot. Two of them was twelve foot; that's mark twain. Three of them was 18 feet. And they'd tell us; we'd knock them off when they got 18 feet. . . because that's no bottom to us with a tow boat because we only draw 8 ½ feet. . . . That was before we had electric speakers. And they had a big long megaphone, and they would holler back to us how many feet deep it was. . . . They would say, "Mark twain," they'd sing it, most of them, sing it to us. And mark three was "Mark three." And then they got the electric sounding devices, and we were looking at a meter right in front of us. We knew what [the depth of] each side was; we had two of them, one on each side. And that's in operation today on them towboats. They have a sounding machine out on each corner of the tow, down about two feet in the water, and it's telling us every second what the depth is. But before that it was that lead line. And at night time it was out there, and if we had box barges with cargo box on it, they [the deck hands] would tie themselves on to that hand rail, so if he got over balanced, he wouldn't fall in the river out there. And that's the way we went up the river or down the river with that man sounding, telling us how deep the river was. (3 July 1997)

Captain Russell reports that he began working with the electronic gauges in the 1930s. The electronic gauges made navigation somewhat easier and reduced some of the risk in the job.

Although he really knew the river, he was not a fisherman while he was on the river, although he enjoyed fishing after his retirement. During the war he recalls that meat was scarce, so he purchased fish for the crew from the coastal and river fishermen:

I bought them during the war; you know, we didn't have no meat. I bought fish; I traded fishermen gasoline, I traded them coffee, sugar. What they couldn't buy, we had plenty of it. We had all kinds of stamps and tickets and money and everything. But we couldn't find no meat. And I'd buy fish, and even when I was in running the canal, going to Mobile, Alabama, I'd hear one of them fishermen . . . talking to his buddies; he'd say, "I've got to pull up my nets; I'm about to run out of fuel."

I have to come in on the radio when they'd get through talking, saying, "Where about you at wanting some fuel?" . . . He told me where he was.

I said, "Well, I'm in this big river boat over here. You see me?"

"Oh yeah, I see you!"

I said, "Well, you got any fish, or oysters, or shrimp, or anything you can swap me?" and he wouldn't hold but thirty-five gallons of fuel. I'd swap him his fuel for fish and that's the way we got fish and shrimp when we down in salt water area. And up on that Mississippi River, we'd blow the landing whistle when we got close to his place where he could hear it, see, and he'd get all his fish together in a tub and bring them out to us in the river. (16 May 1997)

Once when his tow boat broke down near Greenville, Russell did the only fishing he ever did on the Mississippi, using "telephoning," a means that is now illegal, but was a clever new invention at that time:

We had to tie up to the bank, tie the tow off. And I had one of these telephones, called ringing them up. . . . So I went along the side of the barge with the thing down in the boat, and I had two guys in the boat, the paddle boat, going along on the outside, and them catfish, they just come up belly up with the electric current. . . And I caught enough to feed the crew that morning. (16 May 1997)1

Controlling the River

During his stint with the Army Corps of Engineers, Russell had the opportunity to see major changes in the Mississippi River as the corps worked to control river flooding by changing the channel by making cut offs. Russell provides details of these changes in his oral history on the subject. He notes that in the early 1930s diesel boats rather than steam boats were used on the Mississippi. Diesel boats were able to get through the cut offs that the corps was making at that time, but the sternwheelers could not make it upstream in the faster current created by the cut offs. Russell gives a brief account of how this came to be:

After the '27 flood, the army engineer office in Washington D.C., the chief of all engineers, put out a circular among all the top engineers at to see if somebody could come up with a solution to eliminate major floods on the Mississippi River. . . . There was a general—he was major I guess back in them days—he come up with this solution that one of these old long bends maybe half a mile across the neck here, maybe ten, twelve, fifteen miles around that bend. [He] cut that off right there, shortened it up, and he took a hundred miles a little over a hundred miles right over the middle Mississippi River and shortened it. He started that in 1930, in the early thirties. . . . Well, the, the cut offs was in my time. Now that would be the biggest change that's ever happened on the Mississippi River. (16 May 1997)

Russell witnessed some of the making of the cut offs, as he reports in his following recollection:

When they dynamited the plug on Sarah Island cutoff, we had a bunch of reporters on the boats; . . . one of them was a woman. And I think we had about six or seven people on that yacht. And I had a life jacket for each of them on the back of the boat, on the back of the cabin and had a roof over the whole boat, from the pilot house back. And I had around that curve in the boat on the top of the cabin a life jacket for every one of the passengers. So when they was setting the dynamite, the general said, "How far up do you think we need to go, Russell?" [to get away from the blast]

I said, "General, I'd like to go about a half mile anyway." And when they touched that dynamite off—I don't know how many pounds they had, a hundred pounds—it blowed that hole, a big hole in that thing, and the water started rushing through it. But the moment that that dynamite went off, that shock wave hit the boat, and it done that [gesturing a major tilting] to the boat, and it scared some of the passengers, see. . . . That woman, she said when it shook the boat, she said, "Where's the life preservers?"

I said, "They are right around the cabin there; all you have to do is walk around the cabin and get any one of them you want.

She said, "It's a funny place to have them out there."

And I said, "You can't get in the river in here." . . . The crowd that they had aboard the boat was going wild. (16 May 1997)

Russell, on the other hand, was cool and collected, as usual, ready for whatever the job demanded. He continued to follow and learn all of the cut offs and the years they were made on his massive collection of Mississippi River maps. He notes that the cut offs, such as the one in Greenville, Mississippi, in 1935, made a drastic difference in the river: "The old pilots that had come back to see Greenville—they didn't know where in the world it was because there was no resemblance in the shape of the river here today and the way it was back in the thirties" (16 May 1997).

Russell lived through all the major corps-made cut offs of that era and was considered even into his later years to be an authority on the changing river channel. In fact, he was called as a state's witness in 2000 in a dispute over the public use of Gassoway Lake, north of Lake Providence. The state claimed that the lake was public since it joined the Mississippi in times of flooding. The Monroe News-Star gives the following account of his being called to testify in this matter:

Among the witnesses the state says it will call is a 96-year-old former professional Mississippi River pilot, navigator, and boat captain.

The state says that Capt. Oren Russell of Baton Rouge, "witnessed use of landings on Gassoway and the Mississippi River." It says that, "Around 1944, Capt. Russell was working for the Mississippi Valley Barge Lines when a tow of barges broke loose from their moorings at Kentucky Bend above Gassoway and Grand Lake. The barges were carried downstream by the current into the headwaters of Gassoway, when they were recovered by Capt. Russell. He is familiar with the landings on Gassoway and will describe them along with other commercial facilities, boats, and cargoes. (Hatten 6A)

Russell continued to work for the Army Corps of Engineers until after the beginning of World War II. He recalls being out on the Mississippi when he learned that the war had started:

When Hitler marched on Poland, we were coming down the river with five French Engineers, had army engineers on the boat. And we got to Rosedale, Mississippi, coming around the bend looking at the upper landing at Rosedale, Mississippi, and saw a guy with white flag on the pole, waving. [We] got on down there pretty close to it. I told the chief of the party, I said, "Something's wrong." I said, "There's somebody out there on the bank that wants to stop us." I said, "Do you want me to turn around and go on by there and see what they want?"

He said, "Yeah, I guess you better."

So when we got up in about hollering distance of the bank, they said, hollered, "Hitler has marched on Poland. War, second world war has started." Well, them French engineers went crazy. They wanted to get off right then. Well, they knew they was going to be next. And they [the landing] just had that one car, and there's five of them and, they had to get all their stuff. They had bags and briefcases and everything on the boat.

I said, "You have two cars down at the lower landing. I'll be at the lower landing in about an hour." The driver [at the landing] said, "I can have another car here in that time." We put them off, and they took them to the closest airport so they could fly back [home]. But that was the most excited bunch of people—men—that I was ever around. Man, they was, they just went all to pieces. (16 May 1997)

The war brought an end to the major work on the river, and the corps turned to other projects, so Russell used his river knowledge to obtain a job as a tow boat captain.

Dangers of the River

After his work with the Army Corps of Engineers, Russell worked as a tow boat captain on various barge lines from 1943-1985. Since barges do not have a means of power to move themselves, tow boats are used to push them along the river. A small tow boat can push many large barges that are tied together. The number of barges that a tow boat can handle is dependent on the horsepower of the boat itself. Russell notes that the "average barge is 35 by 195 feet (1100 tons). Coming downstream, we never over 5 lengths, but we can go out to 5 widths, so 23-35 barges is big a tow. A 35-barge tow requires about 10,500 horsepower boat to bring it down safely" (29 June 1997). Russell explains the process of picking up a group of barges, termed a "tow," to push north with the towboat:

When we pick up a north bound tow in New Orleans, we have to put all those barges together, and we have blocks in the pile house—miniature blocks—and we lay out our tow with those blocks; the captain is responsible for that. He tells the mate how he wants the barges placed and where. We have maybe 15-20 barges to go north [to] the places up and down the river where we drop off those barges like Greenville, Vicksburg, Memphis, Cairo, Illinois. Cairo is a terminal up there. Part of the barges go up the upper Mississippi all the way to St. Paul, and part of them go up the Ohio River to Pittsburgh and all ports between. We put those together, wire them together with one-inch cables with ratchets and tie them together so they will be like one big piece of steel out there. And as long as we don't hit the bank, or hit a sandbar, those barges will stay together, but if we hit the bank, we liable to break up our tow. (29 June 1997)

By the time he became a tow boat captain, he was quite familiar with the river and its lights. For example, he worked five years for one company and ran 2200 miles one way and never referred to the light book: "I had a mental picture up here of the Mississippi River from St. Paul to the Gulf of Mexico, and on the right from Cairo up from Pittsburgh down. For 5 years I was on a run 2200 miles one way by water. So I didn't have to look at my map; I had that map up here already" (3 July 1997).

Tow boat pilots working with barges have even more to learn about operating on the river. To indicate which way the boat is travelling, the pilots use a traditional system of communication with the boat whistles which Russell describes:

If the up-bound boat blows one whistle, and the down-bound boat wants that side, he'll blow 4 short blasts of the whistle, and then 2, and the up-bound boat has to give him the side he wants because the down-bound boat has the right of way, and that's on account of you have less control over a down-bound tow than you do up bound. (28 May 1997)

He recounts his training and the different companies he worked for, along with his safety record:

But in that space of time, I worked for different companies, and I had a master's license and pilot license. I could get a job anywhere I wanted to work. I could work anywhere. And . . . I worked for a different bunch of people because I made up my mind when I left the government, if I was going to sacrifice my home life, I was going for the top dollar. . . And whoever paid me the top dollar was where I went to work. Because I had a safety record that, I had no accidents. . . . I had [the boat run] aground a time or two. But I never had an accident with another boat or never hit a bridge pier or sunk a barge or anything in my whole career. (16 May 1997)

Russell's experiences as a tow boat captain put him in more danger than his previous position with the corps. The captain and pilot must be on constant watch, according to Russell:

It's hazards out there all the time. Sometimes something unexpected will show up, and you've got to decide how you're going to come out of it, and it's up to the captain or the pilot on the boat, whichever is on watch. We work 6 hours on and 6 hours off. The pilot, he knows the river as well as the captain, but the captain is like the superintendent on a construction job, and he has the last word. (28 June 1997)

Russell explains one of the greatest hazards: the eddies, which have caused major accidents:

The worst part of [the dangers] is the eddies that form all along the river underneath and off of points of land, and the eddy is the worst part. [If] you get caught in an eddy, especially swimming, you're just about going to lose your life. Looking at it, the surface of it [the river] might look smooth, but you get in it, and that water is going in every direction in a circle, just boiling in all directions—they call it an eddy, and that's the dangerous part of the river. . . . They form mostly under a point [where the river makes a big bend] Most of the points [of land] has an eddy under it. Some are small. One of the big tow boats—the Natchez—under the Greenville bridge—was going upstream and caught that eddy as it was emptying. It fills up and then empties. He caught it on the emptying of it, and it took him sideways into that pier and turned the boat over and drowned all the crew but 4 or 5. (29 June 1997)

Thus, bridge piers, too, present a major danger; in fact, Russell admits that they always made him more nervous, possibly because of stories such as the Natchez: "The worst thing I ever had to contend with, and all the rest of the pilots, is those bridges. Them old big piers out there—they won't move; you can run into them with a big tow and bust your tow up and sink barges, but that old pier don't move" (3 July 1997).

Running aground was one of the dangers of operating at night or in the fog. Russell tells a story of how he happened to run aground and the valuable lesson he learned which probably kept him from worse accidents later:

I'd been running under a cloud. The fog was up and the clouds were down low, and I'd been running under it about 3 hours, just about top of the trees. I had to cross the river from the Mississippi side over to the Arkansas side on what we call a "crossing." I was about middle ways in that crossing when that cloud come down and shut everything out. The only thing I could do was just put in on a straight rudder and hope that I could see the bank before I hit it. But it was so thick and dense, and I had the mate out on the head, and we was talking on the intercom, and he said he couldn't see anything out there, and then he hollered all at once, said, "You're fixing to hit the bank!" He was 20 feet from it before he could see it; that's how thick the fog was. . . That was before we had radar. We didn't get radar until WWII was over. If we had had radar, I would have just kept on up the river, and the accident would not have happened. When we didn't have radar and you had possibility of fog and you took a chance, and it closed you out in a crossing, then that's when accidents happened. . . . Before radar, when the fog was forming, even on the surface of the water, we had to tie up because if you didn't, the same thing could happen that happened to me. That taught me a lesson to tie up before I got shut out. Go to the bank and get that one-inch cable out to a big tree and sit there and wait until the fog lifted before you could move. That happened to everybody—all the boats operating up and down the river. (29 June 1997)

This episode of running aground did cause half the tow to break off and continue on its own back down the river. He could not catch it because they could not see. He explains how he retrieved the stray barges which had gotten a 6-hour start on the crew: "We tied off that bunch of barges that didn't break off with the upper half and tied it to the bank, and we took the light boat and went down the river looking for it. And we found it 25 miles down the river" (28 June 1997). They were able to collect them without any loss of freight and continue on their way; thus Russell maintained his safety record.

Captain Russell is proud that his safety record rivaled that of one other pilot in the Mississippi Valley. In fact, he thinks he was better than that pilot because he was faster: "I could make a lock in about two thirds of the time he'd take. And he was so slow, that he, he just, he was working on that safety and because he knew he wasn't going to get fired for taking time, because his brother was Marine superintendent." He does admit, "It gets real scary sometimes with the tows in the locks (16 May 1997).

While Russell had a remarkably safe career himself, he relates a story about a river accident and its aftermath that he witnessed in 1932. The story illustrates the hidden dangers river pilots faced when towing barges on the river when the river channel had changed quickly unbeknownst to the pilot. According to Russell, a fatal accident occurred in 1932 just above the town of Lake Providence, Louisiana, where the river channel had changed about 30 days before "from one side of the river to completely on the other side of the river." In such a change, the river does not actually go out of its banks; the deep river channel between the banks shifts drastically so that the deeper part of the river shifts to another part of the river. The depth of the channel is of great importance in navigating the river. The accident occurred before the time of government control of the river channels. Russell, who was working for the Army Corps of Engineers, took the inspectors over to the wreck and saw the capsized boat about 5 hours later. He gives an account of the accident and its aftermath:

The name of the boat was Standard, and then, of course, back in them days it was Standard Oil Company, and then they changed it to ESSO Oil and then changed it to Exxon. But this boat was one of their tow boats. They had a fleet about five or six big fine sternwheel boats, and they lost this one at Lake Providence and then they lost another one above Memphis a few years ahead of this one here. About two years, I think, they sunk in about two years of each other. . . . He [the pilot] was going up in slack water, and he. . . was running the bar side, right up above here was a bar, a sand bar. And he was in that slack water next to that bar and when he pointed to that bar, the current was coming down right across it. . . And he shoved out into that, and his barge on the head of his boat caught that current, and it was loaded and was just like a rudder. And it turned him crossways in that swift water, and that boat didn't have too much freeboard [distance from the waterline to the top of a vessel's hull], and over she went. . . . I delivered them [the inspectors] over there, and they inspected and looked at it and wasn't nothing they could do, but they did order their biggest tow boat in their fleet which is a Sprague. She was the largest stern wheel ever built in the world. They called it the Sprague. It was up at Grand Lake, and they got it back down here; that was before we had radios on the boats, and we had to wait till he got in, and then they turned around come back, and he put cables on this thing [the Standard] and tried to move it because this front end out here is in the edge of the channel.

And [another] boat come down and hit it while I was over there. . . . One of the colored guys working for me. . . was down on this end putting lanterns on it late in the evening. One of American barge line boats come down the river, and . . . [my deck hand] hollered back to me. . . ., "Looks like he's going to hit this thing."

I said, "Well, wave this lantern at him." He had a lighted lantern. He was waving that lantern at him, . . . The closer he [the barge] got to it," I said, "Set that lantern down, and run back here. Let's get away from here, man." He was on American Barge Line's boat and he was bringing bales of cotton down the river. And when he hit that thing, it knocked a hole in the bow of the . . . barge. . . . So I pulled on along-side of him, and I said, "Captain didn't you see that man waving that lantern at you?"

He said, "Yeah, I thought that was a log raft."

I said, "You'd run over a log raft with a man waving a lantern at you?" Well, he never said more. So I told this inspector what happened, see, and I said, "Now, I'm sure there might be somebody wanting to talk to somebody about the accident." And so I never did hear from him, and I don't know whether he made a complaint about hitting this object in the river. (16 May 1997)2

Russell reported that ten or twelve of the crew were killed; however, three or four of were rescued on the Stack Island side by an old fisherman, who let them hang on the side of his boat, while "he paddled them in to the island, and they walked across the island towards Lake Providence, and he went around in his boat and they let him tote them across to the bank in Lake Providence." The pilot's body was never retrieved, although a pilot friend of his tried. Russell recalls what he was told about the last view of the pilot:

Well, they said the last time they saw the captain he was out of the pilot house on the top on the roof; the pilot house is built on the top of the roof of the boat. And he was out of the pilot house and he evidently caught in some guide wires on stacks of something and they just never did find him. And he could have been on this, on the, caught on the side of the cabin, see? If it did, his body was underneath the cabin on the bottom of the river. (16 May 1997)

According to Russell, the tow boat itself is "still up there down below. It's gone down so deep, the boat's all hidden" (16 May 1997).

Given the stress and dangers of captaining a tow boat, it is not surprising that Russell finally left the job in 1975, around the age of 70: "I got out of that barge line business because I didn't want to fool with them big heavy tows anymore" (16 May 1985). He admits his fear and is grateful for making it through some difficult situations: "I've been so scared I could jump out of my skin just about, because we get in some tight places. . . I've always said the man upstairs puts his hand on our shoulders and brings us out because it wasn't something that we'd done, something we was trying to do, but somebody has helped us" (3 July 1997).

Delta Queen Captain and River Historian

From 1975 until his retirement in 1985 at age 81, he worked as Captain of the Delta Queen and later the Mississippi Queen, which provided him "with his favorite cargo: people" (Morris). Although his career often took him away from his wife, Wilma Warren Russell, he managed to be a dedicated husband and father, as well as a boat captain. In 1978 he lost his wife after 48 years of marriage. The following year on a river cruise, he met Gladys Ringen, whom he married. Russell enjoyed his last years of work on the river and getting to converse with the retirees and celebrities that took the river cruises. In fact, after his retirement, he loved to go back and visit with the crew and passengers on both passenger boats. Quite the gentleman with his trim stature and authoritative voice reflective of his position as captain, he charmed all with his stories of his life on the Mississippi and its history.

Looking back on his career, Russell recognizes his teachers who taught him the river:

During the war, I was working for one of the major barge lines, and I had an opportunity to meet and talk with people from way back. When I learned the river, I learned it from old men who had learned it from old men. So my memory of the river and the knowledge that I have acquired over the years go back nearly 200 years because I knew the old men that knew the old men, and they was all my teachers, so I was trying to store all that information up here. (3 July 1997)

Given his long life, Russell lived through many changes on the Mississippi River, in addition to changes in the shape of the river itself. He liked nothing better than telling stories about these changes he experienced, as well relating the earlier history of the river. For example, he recollects from his childhood with great nostalgia seeing the old style packet boats stopping at farmers' private landings to pick up freight when they were "waved down." He sadly relates how a historic harsh winter up north caused the decline of packet boats:

In 1918. . . there was more of these boats destroyed because we had a terrible winter. And up on the Ohio River, all the packet boats, they was all wooden hulls. And they couldn't run in the winter time when the ice was in the river. And they was all tied up, a whole bunch of them was tied up at Paducah, Kentucky, there behind Owens Island, which is right in front of town. The Tennessee River come down and emptied in to the Ohio right there behind that island, see. And that's a warm water river. It runs from the south to the north and it don't freeze. And the river gorged up above Paducah, I don't know just where it was, somewhere up in that area, about seven to eight, ten, fifteen miles above Paducah. And when I said gorged, it built an ice dam. The river was full of big chucks of ice, see. Got to that narrow place up there, and it gorged and it built a dam across the river and the ice just piled and kept piling up building big high levees. And when that thing got so much pressure on it, it broke that ice dam. And here come millions of tons of ice just rolling down the river that took everything out in front of it and tore it up and it sunk all those packet boats. (16 May 1997)

In 1997 at age 92, Russell shared his history and expertise at the Smithsonian Festival of American Folklife in Washington, D. C. and the Louisiana Folklife Festival in Monroe, Louisiana. Washington Post columnist Courtney Milloy praised Russell's performance: "Oren Russell's recollections of the Mississippi River's Great Flood of 1927 have been a highlight of the Smithsonian Institution's Festival of American Folklife on the Mall these past few days. Visitors from around the world have sat spellbound in front of a cabin porch where Russell, 92, has told harrowing tales of his days as a truck driver and riverboat captain delivering relief goods during the worst flood in American history." Milloy lauded Russell as a "wonderful storyteller" (B1).3

Russell spent his retirement years in Baton Rouge and later near Springfield on the Tickfaw River, where he lived with his son and daughter-in-law, Oren Warren and Ann Pinkston Russell. There he enjoyed fishing at their camp and telling stories about his adventures. He died August 8, 2004, at the age of 100.

Notes

1. See Gowan for details of the telephoning process.

2. For a photograph and history of the Sprague, built in 1901, and decommissioned in 1948, see Steamboating the Rivers

3. In addition to his praise for Russell in the article, Milloy also questioned the festival's exclusion of the "nasty parts" of history, some of which had been recently published in John Barry's Rising Tide. Russell, who had granted Milloy an interview, was so upset by some of Milloy's statements regarding atrocities against blacks by whites in the flood of 1927 that he wrote a letter to the editor of the Washington Post. In the letter which he sent to me, Russell writes that he was "embarrassed" to be associated with the article, which stated that Russell "did not—perhaps could not tell about the brutalization of blacks forced to work on the levee." Russell responded to that accusation, "I cannot vouch for the veracity of Barry's book, but I can tell you from personal experience and observation that the events stated in the book did not occur in the area of the Mississippi River where I was when the flood occurred, nor did I hear of any such events having occurred in the area covered by the Corps of Engineers, Vicksburg District for whom I worked during the flood" (22 July 1997). Because I had recommended Russell for the festival and served as a presenter, I , too, was concerned and wrote my own letter to the editor, pointing out that the most horrific allegation that Milloy took from Barry actually took place in 1912, not 1927 (Barry 130); some other violence referred to by Milloy occurred outside the Delta region. I was angered by Milloy's using Captain Russell, a man of and honor, to criticize the festival.

Works Cited

Barry, John M. Rising Tide: The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 and How It Changed America. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1997. Print.

Gowen. Emmett. "Phone For Your Fish: The Guts of Obsolete Telephones Are Raising Havoc among Catfish." Sports Illustrated. Sept. 27, 1954. Web. 2 Nov. 2013.

Hatten, Jimmy. "Court to Decide If Public Has Right to Use Gassoway Lake." Monroe News-Star 10 January 2000: 1A +. Print.

Milloy, Courtland. "History without Its Nasty Parts." Washington Post 6 July 1997: B1. Print.

Morris, George. "A Life along the River: Oren Russell Spent 56 Years Navigating the Waters of the Mississippi River." The Advocate. 4 August 1997. Print.

Roach, Susan. "The Folklife Festival's Intentions." Letter. Washington Post 21 July 1997: A20. Print.

Russell, Oren. Personal Interview. 16 May 1997.

---. Narrative Stage Presentations. Smithsonian Festival of American Folklife. 28 June 1997, 29 June 1997, 3 July 1997, and 5 July 1997.

---. Unpublished Letter to Donald E. Graham, Publisher, Washington Post. 22 July 1997. Print. "Sprague." Encyclopedia Dubuque. Web. 2 Nov. 2013. http://www.encyclopediadubuque.org/index.php?title=SPRAGUE

"Sprague, Vicksburg, MS." Steamboating the River. www.steamboats.org. Web. 3 Nov. 2013. http://www.steamboats.org/steamboat-pictures/sprague.html