Jazz, Zydeco, Cajun and Country: Roots-Music Diversity in the Greater Baton Rouge Area

By Ben Sandmel

Introduction

Baton Rouge, Louisiana's capital has long been a city of great multi-cultural diversity. Prominent, longstanding ethnic groups include Anglo-Americans, African-Americans, Italians, Lebanese, Syrians, and—as the city's name indicates—emigrants who came directly from France, as well as French-speaking Cajuns from present-day Nova Scotia, and Creoles1 who arrived in from French colonies in the Caribbean, most notably Haiti. While the aforementioned Canadian emigrants primarily settled west of the Mississippi and Atchafalaya Rivers, their presence in Baton Rouge nonetheless influenced local culture. During the latter 20th century, an influx of new populations from India, Southeast Asia, the Middle East, Mexico, and Central America significantly increased Baton Rouge's diversity, and this trend continues today. In addition, the city's population has grown dramatically during the years following Hurricane Katrina, in 2005, after many temporary evacuees from New Orleans decided to stay permanently. Furthermore, people from smaller towns in Louisiana often move to Baton Rouge for employment opportunities, as is the case with two of the musicians interviewed. This essay was researched before the shootings of July and flood of August 2016, so neither tragedy is reflected in the interviews or in this essay.

My fieldwork for the Baton Rouge Folklife Survey, as discussed in this essay, focused on four musical genres—traditional jazz, Cajun music, zydeco, and country music—as covered in six interviews. The transcribed interviews have been lightly edited for the purposes of clarity and narrative continuity. Great care has been taken to respect and preserve the precise meaning of all original statements, with no changes of nuance. Such editing, however, means that some of the words of the musicians here are paraphrased, as opposed to appearing in completely verbatim quotations in their original sequence. The paraphrased sections appear in italics.

Jazz

Traditional jazz is often exclusively associated with New Orleans. The Crescent City was certainly the epicenter of the evolution of this genre, as exemplified by such first-generation pioneers as Charles "Buddy" Bolden, circa 1895, and second-generation luminaries including Louis Armstrong, Jelly Roll Morton, and Sidney Bechet. However, early jazz also garnered great popularity beyond New Orleans, throughout south Louisiana, and along the Gulf Coast. To cite several examples, the renowned trombonist Kid Ory launched his career in LaPlace, in St. John the Baptist Parish. Bands led by John Robichaux, Claiborne Williams, and "Toots" Johnson drew a large following in New Orleans, Donaldsonville, Baton Rouge, and environs, circa 1900 (Keonig 1996). In the 1920s and '30s, bands such as the Louisiana Six from New Iberia, and the Yelpin' Hounds from Crowley, played jazz in the state's southwestern parishes. Popular in their own right, these bands also influenced the development of both Cajun music and the Creole genre that would come to be called zydeco. There are many other significant examples. The noted folklorist Dr. Joyce Jackson has extensively researched this often-overlooked aspect of jazz history (Jackson 2011).

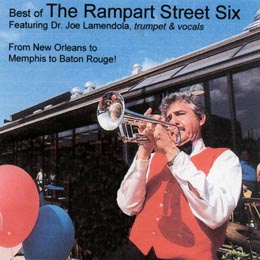

Joe Lamendola: Jazz Trumpeter

Dr. Joe Lamendola was born and raised in the river parishes, and has lived in Baton Rouge since enrolling at LSU at age 16. For decades he performed prolifically in Baton Rouge, New Orleans, and overseas. Although not actively playing at this writing (November, 2016), at age 84, Dr. Lamendola happily reflects that he has "had a very interesting life. … Life's been good, I've been blessed." Among the blessings that Lamendola counts are his dual careers as an optometrist and a trumpeter who plays traditional New Orleans jazz. Wisely realizing early on that musicians often find it difficult to make a steady living, he was still determined to have the best of both worlds.

Tracing his musical heritage back several generations, Lamendola began his training at a young age in his native St. James Parish. By the mid-1950s, he had achieved a sufficient level of musicianship to lead a traditional jazz band.

I was born in Lutcher and raised in Convent, Louisiana. in St. James Parish. I've been playing music since I was ten. For some reason I wanted to play accordion, but the school-band director said, "No," so I said, "OK, I'll play trumpet," and my daddy bought me a little silver cornet. There were musicians in my family on my mother's side going way back. My great-great-grandfather Valentine Babin had 18 children and two of his sons had a band in the Prairieville/Dutchtown area. I assume it was a brass band and that they played cakewalks, ragtime, music like that. I'm totally self-taught, I can read simple piano music, but I mainly play by ear.

I graduated from high school at 16 and went to LSU. Graduated from LSU and went to work at the Shell Refinery in Norco, Louisiana. I got an ROTC second lieutenant's commission and went into the service in 1954. I played the officer's club at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. On the ship over to Europe, I formed a band called the Seasick 8. I was stationed in Austria. I had my horn with me all the time. I taught some Italian guys how to play

"When The Saints Go Marchin' In." Jazz is the only art-form that America invented, but sometimes people from other countries play it better than we do.I got out of the service in 1956 and went back to work in Norco. I lived on Cambronne Street in uptown New Orleans. Every night I would go to the Famous Door on Bourbon Street.2 I got to know everyone in the joint at the Famous Door, and the guys in the band would let me sit in. Guys like Roy Liberto, he was a trumpeter, also Murphy Campo—Murphy was the most unsung trumpeter in New Orleans—and Peewee Spitelera, on clarinet. I'd sit in on songs such as

"Panama" and "Fidgety Feet." The Famous Door had continuous music with two bands alternating; one drummer would hand off sticks to another drummer in the middle of a song. All kinds of celebrities would come in, like Hopalong Cassidy, the cowboy-movie star—just for one. What a great place.Lamendola's pragmatic nature soon took him to Memphis for medical training; however, he continued playing music, even recording an album and playing a regular gig at the historic Peabody Hotel, earning accolades from local audiences.

I decided that I wanted to become an optometrist, and I enrolled at the Southern College of Optometry in Memphis. I brought my horn with me. I saw a notice for a trumpet player needed at a place called the Keller Club. I got the gig, but then we had a hassle with the owner, so me and the drummer, Rudy Balius, we left and we formed our own Dixieland band. We cut an album,

Jazz From Dixie, at Pepper Records in Memphis. The guy who engineered the session was a guy named Ronnie Capone, from Donaldsonville, Louisiana. Ronnie was also a drummer, but the main thing is that he went on to become a prominent audio engineer.3

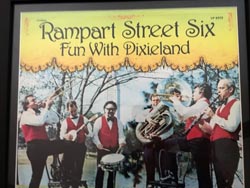

Rudy Balius and I called our band the Rampart Street Six. We got a longtime gig at the Peabody Hotel, we played there every Friday and Saturday night for a year when I was in Memphis. The manager of the hotel, Bill Campbell, created a venue for us in the Peabody called the Carnival Room. Bill Campbell loved us, the people loved us. I didn't consider myself to be a great player but I was a great showman, with a million jokes and one-liners, and I could keep the crowd entertained. But while I was in Memphis I did receive a great compliment when a music critic named Bill Bruning wrote that I sounded like a mixture of Louis Armstrong and Bobby Hackett. Hackett used to play with Glenn Miller, Benny Goodman, and Jackie Gleason, and he had a beautiful tone. So seeing that in print written by a music critic made me feel really good. 4

And another thrill, when I was in Memphis, my band opened for Pete Fountain at a March of Dimes benefit in January, 1962. I played at the Peabody for a year while I was in optometry school. I never missed a gig, not even when I was studying for my optometry board exam.

Before returning home to live in Louisiana, Lamendola had an opportunity to travel to Las Vegas, where he enjoyed seeing many of the period's most celebrated entertainers.

But I did take one great little vacation. I got through playing one night; my friend had a '58 Corvette. We put the top down, left Memphis, and drove all night to Amarillo. The next day we drove to Vegas and we went to The Sands, where all the "Rat Pack" hung out.5

So we walk into in the lounge at The Sands and it turns out it was Frank Sinatra's birthday and everybody from the Rat Pack was there. They had just wrapped up filming

Ocean's 11 and everyone was in town: Richard Conte, Dean Martin, Sheree North, the Crosby Brothers, Elizabeth Taylor, Eddie Fisher &and then walking down the hall is Jack Entratter, the owner of The Sands, with Marilyn Monroe on his arm, wearing a Jean Harlow gown—she was Sinatra's date for the evening. What a night!I graduated and stayed on in Memphis, kept playing music. I had my degree in optometry, I was an O.D. I wanted to play my music, too, but I wasn't sure how far that would take me.

Lamendola returned to Baton Rouge where he opened his own optometry practice in October of 1962. Upon his arrival, he was hired to play a regular gig at the city's private country club through which he made many professional connections that helped bolster his musical career. In 1966 he opened his own club, the Speakeasy, located on Stanford Avenue. During the ensuing decades, Lamendola performed at both private events and governmental ceremonial functions in an impressive array of venues—locally, nationally, and internationally.

There were some great jazz musicians in Baton Rouge then—especially Lee Fortier and Buddy Boudreaux. Lee was a trumpeter who had played with Woody Herman. Buddy played sax and clarinet. They put together a big band called The Buddy Lee Orchestra. One time they were co-billed with Buddy Rich6, plus they backed up a lot of major artists who came to Baton Rouge—Andy Williams, Burt Bacharach, and Bob Hope, and they opened for Tony Bennett

(Wirt 2015).I hadn't been back in Baton Rouge a week before I got hired to play at the Baton Rouge Country Club. I put together a four-piece band with piano, bass, and drums. I replaced a trumpeter named Bill Prine who went to work with Ringling Brothers Circus. I told the country club people "I'm only playing 3 hours. Whoever put it in stone that had a gig had to be 4-hours?" I'm the first bandleader in Baton Rouge who put a stop to that.

From playing at the country club I met all kinds of people. I played lots of society weddings. Played the City Club. Chef John Folse and I went to Bogota, Colombia, and presented "A Taste of Louisiana." I played at the reopening of the Old State Capitol building. Did a concert in Venezuela, co-sponsored by U.S. State Department, Pan Am Airlines, and the state of Louisiana—and at 11 A.M. on a Sunday morning we had a packed house! Played for the

[Declaration of Independence] Bicentennial in Philadelphia in 1976 for Mayor Frank Rizzo, then I went to Italy two days later. Played in Costa Rica for Bob Odom, who used to be the Louisiana Secretary of Agriculture. I even worked with Danny Barker, the great New Orleans guitar and banjo player.7 That was a thrill.One of my favorite people to play with was Father Frank Coco.8 He was a priest in New Orleans who played clarinet. He was on the scene for forty years. And one of my great thrills was when I played for the unveiling of the Louis Armstrong statue in Jackson Square on July 4, 1976.9 We were playing

"When It's Sleepy Time Down South" and Leon René, who was one of that song's co-writers, Leon jumped up on the bandstand and started singing it with us—he was so appreciative of what Louis Armstrong had done for him by recording his song.10 It became one of Louis' signature tunes.Italian-Americans musicians such as Lamendola have been integrally involved with traditional New Orleans jazz since its inception (Raeburn 1991). The most notable example, in terms of public perception, is the New Orleans trumpeter and vocalist Louis Prima (1910-1978). Prima's bilingual repertoire, blending Italian-American and African-American cultures, among other sources, made him a national celebrity for more than four decades. Given Lamendola's heritage, a similarly multi-cultural approach might seem likely, but such is not the case:

My last name is Sicilian. In Sicily, it's pronounced LaMENdola, my father's side of the family has Sicilian ancestry, but none of my Italian ancestors played music. I used to do one song in Italian, "Che La Luna" by Louis Prima, you know he was from New Orleans. But what I love to play is jazz—traditional jazz, nothing way-out—you know, Louis Armstrong used to say "It ain't no crime to play the melody." My idols were the Dukes of Dixieland, Harry James, Bunny Berigan, and, most of all, Louis Armstrong—Louis was an authentic genius. If the kids today would get to hear this great music I think they would love it like I do—but, unfortunately they don't get to hear it.

Zydeco

Zydeco (pronounced ZY-duh-coe) is the exuberant dance music of southwest Louisiana's black Creoles, many of whom speak a variant of Louisiana French or have ancestors who did. Stylistically, zydeco is a rich hybrid, with a core of Afro-Caribbean rhythms, blues and R&B, and Cajun music. A wealth of other elements may be incorporated, ranging from country, rock and reggae to rap and hip-hop, and even television-show theme songs. Traditionally, zydeco is sung in French, although English has become increasingly prevalent, and its lyrics are often improvised. It is absolutely not intended for passive listening. As accordionist Clifton Chenier (1925-1987), known as "the King of Zydeco," definitively stated, "If you know how to dance, then you can dance behind someone beating on an old gallon bucket. But if you can't dance to zydeco, you can't dance, period" (Chenier 1982).

The word "zydeco" is often explained as an elision of the French phrase "les haricots" (pronounced lay-ZAH-ree-coe). The phrase "les haricots sont pas salés" appears frequently in black Creole folk music. Literally translated as "the snapbeans are not salty," it is also a metaphor for times so hard that people cannot afford salt pork to season their food. "Les haricots sont pas salés" was first documented by folklorists Alan and John Lomax—in a field recording made in Jennings, Louisiana, in 1934, of the song "J'ai Fait Tout Le Tour Du Pays," by Jimmy Peters and a group of ring-shout/juré singers. This riveting performance constitutes a significant cultural milestone.

By the early 1960s the pronunciation of "les haricots" eventually elided into the phonetic approximation "zydeco," with some variant spellings. Heard in many traditional songs, "les haricots sont pas salés" (and the shortened "les haricots"/ zydeco) gradually generated several separate yet related meanings: the title of a song, "Zydeco sont pas salés" ; the name of the musical genre represented by that song; the social gatherings where such music was played; and the dance steps and the act of dancing that the music inspired. As the writer Susan Orlean noted, "In theory, this meant you could zydeco to zydeco at the zydeco" (Orlean 1990: 179).

Zydeco functioned below the radar of mainstream America, strictly within the Creole community, until the mid-1960s when Clifton Chenier brought it to new audiences on the folk- and blues-festival circuits in the United States and overseas. In addition to its Creole folk roots, Chenier's music incorporated cover versions of R&B and blues hits, by the likes of B. B. King and Louis Jordan, which he adapted to the chromatic accordion and sang in French.

Zydeco shares many traits with Cajun music—most notably its signature instrument, the accordion—but the two genres are hardly identical: Most Cajun bands feature the fiddle, which is rare in zydeco, while the horn sections prevalent in zydeco are atypical in Cajun music, although more common than 20 years ago. Through most of the 20th century, zydeco tempos tended to be more assertive and syncopated than those heard in Cajun music, but that distinction has also blurred in recent decades.

The mid-1980s saw a brief national craze for zydeco, Cajun music, and south Louisiana cuisine. This fad had its crass commercial aspects, but it also brought well-paying work to zydeco and Cajun musicians, including record deals, film appearances, and heightened performance fees. As Melvin Chavis notes in the following interview, that trend has now receded—but zydeco and Cajun music remain firmly established in terms of mainstream awareness, with enthusiastic followings around America and overseas.

Melvin Chavis: Zydeco Accordionist and One-Man Band

Most of Louisiana's French-speaking citizens live in an expansive swath of the state that is often referred to as "the Acadiana triangle." The base of this conceptual pyramid runs along Louisiana's coastline beside the Gulf of Mexico. Its southeastern corner lies between Lafourche and lower Jefferson parishes, almost due south of New Orleans and just west of Grand Isle. Avoyelles Parish forms the apex, some one-hundred miles north of the Gulf. Although several parishes that straddle the Mississippi River are considered part of the Acadiana triangle, adjacent East Baton Rouge Parish is not among them; the triangle does, however, include West Baton Rouge Parish, just across the river. This curious and somewhat arbitrary division may exist because Louisiana's French dialects are rarely spoken in the state's capital city, compared to Lafayette and westward into east Texas. The same level of activity applies to French-based cultural expressions such as Cajun music and zydeco.

There are exceptions, however. Melvin Chavis—a multi-instrumentalist and singer who has been performing zydeco in and around Baton Rouge since mid-2006. "No one else that I know of who's based in Baton Rouge plays zydeco," Chavis says. Chavis is also atypical in that he presents a full-band sound by performing solo with a pre-recorded accompaniment of guitar, bass, keyboard, computerized drum tracks, and washboard. ("Washboard," as used here by Chavis, is synonymous and interchangeable with the terms rub-board, scrub-board, and the French word "frottoir," all of which refer to the corrugated-metal percussive instrument that is unique to zydeco.)

Some folklorists who document oral/aural tradition may feel that this approach clashes with purist notions of authenticity. Nevertheless, the use of such electronic-instrument technology has been quite common since the mid-1980s. Contemporary researchers working in any traditional American genre are unlikely to encounter any musician who has not been influenced in some way by mass media and computers. Chavis explains that his preference for working solo comes not only from his openness to available technologies but also his past experiences in dealing with musicians.

I've been in bands since I was 15 years old. I tried to get a band together when I started playing zydeco. But there's too many different personalities to deal with, and at my age I don't want to go through all that, so now I do a one-man show. "The band" always shows up on time, everyone's in a good mood, and when I call out a song there's no complaints like, "Let's not play that one, let's do something else." I play for people who want to dance. I do a lot of house parties, and weddings, things like that. I also try to play at the farmers' market, downtown Baton Rouge one Saturday a month. It's much better than playing clubs. Almost all my gigs are a handshake, no contract, my word is my word, most people pay me before I get started and I love that. When I was playing in a band at clubs, oh man, after you got done sometimes you had to look for the owner, or the door money wasn't right, those kind of problems.

The furthest I've played outside of Baton Rouge is Crowley, west of Baton Rouge; north, a wedding party north of Angola; and east in South Carolina. I'm retired, and this is a hobby for me. I don't want to go on the road and drive so far that I have to get a hotel room and end up spending all the money I make. So I stay in this area, and I only take the gigs that I want, when I want. If I get a call asking me to play, first I ask my wife if she has plans for us. And if she does then I say "I'm sorry, I can't make it." My wife loves zydeco, I've known her since the 5th grade, and we've been married for 46 years.

Melvin Chavis was born into zydeco, in Church Point, Acadia Parish, in 1950. "My daddy played accordion a little," he recalls, "and my uncle, Valmon Chevis, he was the known accordion player in the Church Point area." Despite his family's strong ties to zydeco, the teenage Chavis—like many of his peers—became disinterested in the genre, turning instead to soul music and rhythm and blues.

This underscores Chavis' eclectic musical taste, and disproves the notion that Louisiana's tradition-bearers are culturally monolithic:

My wife is in the choir at our church, and I play with them every other week. We practice Wednesday nights; we have drums, organ, and guitar and I play bass. So I don't just play zydeco only. I play some R&B, too, but I got to put my flavor to it. My philosophy is if you want to hear the song exactly the way it was recorded, go buy you a CD. There's a few jam sessions around here that I go to sometimes, but I have to be careful. I only sit in with certain bands when I know the bass player can go where I want, and I know the drummer has the right rhythm. Sometimes you get up there, and someone else will make you look bad even though it's their fault.

My family name is Chevis, but on my birth certificate it's Chavis, with a letter A, because that's how whoever filled out the paperwork happened to spell it that way. When I was a kid, my parents would take the rug off the floor in the house, move all the furniture, and invite some relatives and neighbors over. They called it a house dance, or a la-la. My uncle, Valmon would sit down and play accordion, just him, sometimes someone would pick up a washboard. People would dance all evening. That was our family's way of letting loose.

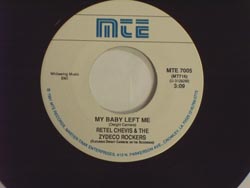

As a kid, zydeco to me was like old-folks' music. What I really liked then was R&B and soul. [This approach was typical of Chavis' generation; the late Stanley "Buckwheat" Dural (1947-2016) the leader of the band Buckwheat Zydeco, followed a similar career path by starting out in R&B before "coming home" to zydeco .] That's what we listened to on the radio; there was no zydeco on the radio then: there was Cajun music but no zydeco. I liked blues, too. I'd listen late at night to a DJ named John R. out of Nashville, the station was WLAC.11 If the weather was a certain way then I could pick it up, but it didn't always come through. I learned some about playing from my older brother, Retel. he's deceased now. He played bass and guitar; years later he got into zydeco and started a band called the Zydeco Rockers and recorded a 4512 in Crowley.

I started playing music in public when I was 15, in 1965. I played bass in a band called the Swinging Seven. Every Saturday evening, being Catholic, we'd go to confession at our church and after confession, I'd go across the street from the church to a little wash-house, and that's where we would practice. We played songs by James Brown, Jackie Wilson, Otis Redding—that's the kind of music that was really kicking for us back then. Nothing in zydeco.

Back in the day, Church Point was the place to go. When I go back there now I feel sad because all of the clubs have closed down. There used to be a whole strip of them on Main Street, Highway 35. One place I remember just out of town was called "Shah-pee," that was the owner's nickname and the name of the club, too. There was another place owned by a guy named Joseph Bellard; we called him Joe. One Saturday night the guy who Joe had hired to play couldn't make it, so Joe wanted us to play instead. He asked my dad, and my dad said, "No." The rest of the guys said, "Please." They begged my dad and my dad finally broke down; once he found out adults would be there to keep an eye on us, he said okay. We went over there and played our songs by James Brown, Jackie Wilson, and others. We did a four-hour show, with one fifteen-minute break, and Joe paid us fifteen dollars for the whole band. There were five of us so we each made three dollars and, man! At that time I was making five dollars a day, working in the fields, then I made three dollars having fun. Man, look here, that was great! And that's how the band started.

Like Joe Lamendola, Melvin Chavis realized early on that a full-time career in music was financially precarious. His long tenure in the military afforded some opportunities to continue playing, but these were limited.

We started traveling from Church Point to Opelousas, Welsh, and Lake Charles, playing different places. I played with the Swinging Seven through Christmas Eve 1968. Then in February of 1969 I joined the Air Force. I played music off and on during my career in the Air Force. I was stationed in Guam for a while, and me and some guys started a band there. I was stationed at Barksdale AFB in Bossier City near Shreveport. I played a few gigs there but playing music didn't fit with my security clearance so I set it aside. Then in 1985 I moved to Baton Rouge to work as an Air Force recruiter. And that is right around the same time that my cousin, Boozoo Chavis, came back to zydeco after being away from music for something like twenty years. Going to hear Boozoo is what got me playing zydeco.

Wilson "Boozoo" Chavis (1928-2001) was one of zydeco's major pioneers, recording the genre's first popular single, "Paper in My Shoe" in 1954. Believing he did not receive a fair share of the record's profits, Chavis withdrew from the music business in the early 1960s and spent the next twenty years training racehorses and raising his family. In his fifties Chavis decided to give music a second chance, and was soon packing dancehalls along the "crawfish circuit" of south Louisiana and east Texas (Olivier and Sandmel 1999). In a time-honored folk tradition, Chavis played with an idiosyncratic disregard for conventional musical structure, "jumping time" by changing chords at random, or dropping and adding beats. Melvin Chavis plays a far more modern and structurally standardized form of zydeco than his cousin. Nonetheless, Boozoo inspired him deeply.

Around 1992 I went to Richard's Club, in Lawtell near Opelousas, one evening, to see my mom. Boozoo was my cousin, but I only knew him in passing. He was quite a bit older than me. He was playing Richard's that night, and when he hit a certain note on that accordion, I got a chill from the bottom of my feet to the top of my head! That was it! I wanted to learn the accordion and play zydeco! My brother Retel got me a D accordion, diatonic, and I got serious. Preston Guilbeaux, another great accordion player in the Opelousas area, my wife's uncle, showed me some things, some basics about playing a triple row diatonic. [Diatonic accordions utilize the whole notes of major scales only, while chromatic/piano accordions, which are common in zydeco, also include flats and sharps.] I started playing and practicing, and that's where I'm at now. I set up my studio, and I'd come in here—the woodshed, you might say—and I still do. I might stay in here until 1 or 2 o'clock in the morning, practicing and honing my craft.

Boozoo Chavis' return to music represented an important cultural moment as Chavis instantly attained elder-statesman status. Many people were shocked that he was still alive. At this writing, the world of zydeco has changed significantly, with many performers pushing the genre's traditional boundaries. Despite such changes and the cultural inroads of English lyrics, Melvin Chavis finds much to admire in contemporary zydeco, even though he concedes that the height of its national popularity may have passed.

In 1984 on the zydeco scene you had Boozoo, Rockin' Sidney—he had that big hit "Don't Mess With My Toot-Toot"—John Delafose, Willis Prudhomme, Rockin' Dopsie, the Sam Brothers 5, my brother's band, Henry Clement from Crowley, people like that. I was listening to all of 'em. I saw Clifton Chenier play, before he passed. It's great that zydeco is coming back. We have a whole lot of musicians that's playing the music. They're changing it, but it has to evolve and it is evolving. You got some artists now that's supposed to be playing zydeco but they sound more like hip-hop, and everything's in English. But then I don't speak French. My mom and dad spoke fluent Creole to each other, but they shut it down amongst their kids. They didn't want us to learn, they just spoke English to us. And speaking French at school was no-no. I went to Our Mother of Mercy Catholic School in Church Point and back then the mindset was that everybody needs to know how to speak English.13

Some of the zydeco artists I enjoy today are Geno Delafose, Jeffery Broussard, [the late] Beau Jocque, Keith Frank, Lil' Nathan, and his dad [Nathan Williams, leader of Nathan the Zydeco Cha-Chas]. I think zydeco had its peak in popularity in the '80s and '90s, around the time that Boozoo came back, and Rockin' Sidney had "Toot Toot." When zydeco had its own category at the Grammies—[the category was Cajun and zydeco]—I thought that was great, but that's not happening anymore, now zydeco is more local and it's going to stay local. A lot of your local musicians will go play overseas and festivals up north, but it's not the new exciting thing that it was. It has leveled off.

Louisiana's rural Creole community, extending into east Texas, has a strong affinity for cowboy culture, often based on the rigorous personal experience of working with horses and cattle on the region's rural prairies. The most flamboyant expression of this tradition unfolds at trail rides, elaborate gatherings during which participants ride horses on a long, leisurely course through the countryside. Many trail riders proudly sport cowboy hats and boots, large decorative belt buckles, and western-style shirts with faux-pearl snap buttons. The trail riders make frequent stops for dancing and visiting at bars, dance halls, and friends' houses. A zydeco band may follow the riders while performing on a flatbed truck, powered by a portable generator, or a sound system will play zydeco CDs. At the end of a ride, there will be a lavish spread of home-cooked food, south Louisiana style, and the party will continue.

I just want people to know that anyone can play music if they put their heart into it. I am loving playing my music now. And I am really excited about a new song that I wrote and recorded called "Zydeco Trail Ride." I've been going to trail rides for years. There's an older guy that leads them, playing zydeco [recordings] out of an old bread truck. Everyone calls him "Bread Man." He goes to a trail ride almost every weekend, out around Crowley and Church Point, and he lets me know where the next one is happening. As Melvin Chavis joyfully sings "The weekend's here, time to have some fun, we're gonna dance the zydeco 'til the morning comes."

Zydeco Trail Ride, verse 1

It's Friday evening,

I just got paid.

It's off to the mall,

To get a new shirt,

Gonna starch it down,

Just like my jeans.

There's a trail ride tomorrow.

I got to be real clean.

Got my cowboy hat with my matching boots,

Big belt buckle, and my cowboy hat.Goin' to the trail ride, zydeco trail ride.

Goin' to the trail ride, zydeco trail ride.

Goin' to the trail ride, zydeco trail ride.

Goin' to the trail ride, zydeco trail ride.

Cajun Music

Currently in the fifth decade of a rich cultural renaissance, Cajun music is most frequently performed today by bands in which the diatonic accordion is the dominant signature instrument. Fiddles, acoustic and/or electric guitars—and in some cases, steel guitars—provide accompaniment and contribute solos alike, and most bands are anchored by a rhythm section of an electric bass and a full drum kit. This familiar sound and visual image belie the fact that, during its approximately 250 years of existence, Cajun music has undergone significant changes in terms of instrumentation and repertoire. Neither the accordion nor "Jolie Blonde" were always Cajun music's identifiers.

The individuals who emigrated to Canada from western France arrived with two rich musical traditions in tow: fiddle music and a cappella ballads. Some of this music had clearly discernible medieval roots. The fiddle repertoire was primarily played to accompany dancing and included such song forms as waltzes, reels, contre-danses, jigs, mazurkas, and schottisches. The a cappella ballads ranged from centuries-old historic narratives to children's play songs and lullabies, and were sung more often by women than by men.

The accordion was introduced to the region during the latter 19th century and caught on quickly as the only instrument loud enough to cut through crowd-noise at a dance. With the advent of electricity—and electronic amplification—in southwest Louisiana in the 1930s, acoustic instruments such as the guitar and fiddle could match the accordion's volume for the first time. So could vocalists. As a result the accordion temporarily faded from popularity from the '30s until the end of World War II; those years came to be known as "the Cajun string-band era."

Although Cajun music has experienced considerable interaction with Anglo-American country music, a common misconception depicts it as nothing much more than country sung in French. The reality is that cultural exchange has gone both ways, and that each genre has exclusive aspects of its repertoire. On the 1952 hit song "Jambalaya (On The Bayou)," for instance, the country star Hank Williams used the melody—note for note—of a traditional Cajun song known both as "Grand Texas" and "L'Anse Couche Couche." Conversely, the popular and often-recorded Cajun song "J'etais au bal hier soir" makes verbatim use of the traditional country song "Get Along Home, Cindy" (Sandmel 1999).

Ann Vidrine: Cajun Fiddler

Since 1990, fiddler, vocalist, and songwriter Ann Vidrine has worked as a cultural crusader for Cajun music in Baton Rouge. She was born and raised in the heart of the Acadiana Triangle, in Ville Platte, Evangeline Parish. The town has a rich musical history that ranges from notable performers including the Cajun accordionist Austin Pitre to such famous Cajun dance halls such as Snook's (Pitman 1997). Ville Platte is also home to Swallow Records, a company that makes important contributions to grassroots cultural preservation—with a dual approach that is both folkloric and commercial—by recording and promoting Cajun music, zydeco, and swamp pop.

A third-generation Cajun musician, Ann Vidrine began playing music at a very early age alongside the family elders who taught her. She spent her adolescent years playing guitar, and picked up the fiddle some two decades later. Despite Cajun music being Vidrine's major influence she was also always open to various mainstream popular genres, disproving the notion of Cajun culture as isolated and self-contained. After graduating from college with a pre-professional degree, Vidrine decided to pursue her passion for music by starting her own business as a professional entertainer.

My mom got me an acoustic guitar at age 8 and I started playing it right away, along with my grandfather, Leon Vidrine, and my Uncle Eloi Vidrine, in The Cajun Fiddle Band. We played weddings. Through my teen years I played in church, and at weddings, as a guitarist. To me the purpose of Cajun music is to make you dance; I played for the grand opening of Trader Joe's one time and a young couple started waltzing and I liked that. My fiddling came in my mid-20s. In my uncle's band there was fiddle and accordion—my uncle played both instruments and sang. There was a drummer, plus me on guitar, it was a three-piece band. I'm the only one in my family playing music today. I grew up listening to my dad's Cajun records by Harry Choates, Doug Kershaw, Rufus Thibodeaux, and Doc Guidry. In 1989, I received a grant to study with Oran "Doc" Guidry from the Louisiana Division of the Arts. And Doug Kershaw invited me to join him on stage in 2002 during his concert at the Casino Rouge here in Baton Rouge.

Growing up in Ville Platte I also heard a lot of Beatles, soul, rock, and swamp-pop, besides Cajun music. As a guitarist when I was in college I was really into singer-songwriters—Dan Fogelberg, Karla Bonoff, Joni Mitchell—and I performed in a coffee shop called Kirk's. I went to LSU and got a marketing degree. Joseph Campbell recommends creatives to "Follow Your Bliss," and that just rang so true for me.14 I decided to take the plunge and pursue a musical career. The next day I started a full-time business, looking through the newspaper, seeing what meetings were being held—I called them up and got gigs playing at corporate events.

As opposed to many Cajun musicians, Vidrine eschewed playing at dancehalls and focused instead on presenting at schools and libraries. She also developed a downtown walking tour for riverboat passengers who would frequently visit Baton Rouge during shore stops on tourism-oriented cruises. Vidrine filled these "performance-lectures" with minutiae about the state and, more specifically, Cajun culture. She notes, however, that the capital city remains distinct from towns and cities in the Acadiana Triangle. With no other female fiddlers in the city and an exclusive business relationship with the major riverboats, Vidrine's niche business flourished until 2005.

I never did the club scene, I'm more of a school-museum-reception-military reunion type of entertainer, because I lecture too. I created a performance-lecture called, The Cajun Experience that I've presented to students, tourists, and library patrons for the past 26 years. I strived to maintain a 1.5 minute time limit on the topics I cover so that a narrow focus is maintained by audience members. I took a rubber crawfish and cut it and set it up so that I can teach people how to peel a boiled crawfish, because a lot of people don't know the quickest ways. That came to me one night as I was falling asleep, that's how the show evolved.

Baton Rouge is not even a little bit of a Cajun cultural town. The powers with Baton Rouge remind me of the descendants of plantation owners. At the time I was doing my tours I was the only female Cajun fiddler in Baton Rouge.

I am the only one who created a Cajun fiddle walking tour in downtown Baton Rouge, starting from where the riverboats stop, like the American Queen, the Delta Queen. I did that from 1998 to 2005 but when [Hurricane] Katrina hit a lot of the boats went bankrupt and I lost my job.

I would go around with a bag of tricks on my belt, props, 'cause there's wasn't too much to see. In that bag I had a horseshoe that I played like a 'tit fer, a Cajun triangle, but I played it with a nail. Also I would share with them the petrified palmwood, which the official Louisiana state fossil, and banded agate, which was then the Louisiana state gemstone. I would explain how the Mardi Gras colors—purple, green, and gold—symbolize the three gifts of myrrh, frankincense and gold that were brought to Christ at his birth.15 That's the Cajun/Catholic explanation for those colors. There are other interpretations in places such as New Orleans. I would go over some of the different trees that they'll see, and some that they won't see, such as cypress. Then I would play a song or two on the accordion. I would show them pictures of the Louisiana state dog, the Catahoula, and pictures of albino alligators, trivia that's important in Louisiana. My route used to be from the boat dock and around the Old State Capitol and then on North Boulevard. I would tell them about Huey Long. My third cousin, Dr. Arthur Vidrine, was the doctor called in from New Orleans to operate on Huey Long after he was shot.

I walked with my fiddle and my PA system on me. It was a hard job but I'm the one who invented it. I was under contract with the boats, they paid me per head. I've had as many as 62 people and as few as 7. I'd go by the fence by the Old State Capitol building, for instance, there are fleur-de-lis symbols on the iron fence and so from that I'd tie in the French ancestry here in Louisiana and from there to Cajun, and then brain-mapping all over the place I'd make the story, make the tour.

Vidrine remembers the days when Cajun music was disdained as coarse and provincial—an era when, much like zydeco, it could only be heard within its local communities. Vidrine has seen her stalwart traditionalism pay off with significant press coverage and, in 2016, a Folklife Heritage Award from the state's Lt. Governor. Despite such recognition, she has begun to perform less, in part due to her perception of Cajun music's turn to amplified rather than acoustic shows.

For a time Cajun music was put down as old people's music. It wasn't seen as cool like it is today, I think that started in the late '90s. There was an influx of people wanting to learn. I was the only female fiddler in Baton Rouge for years, I was the only Cajun fiddler and singer in Baton Rouge for years. There wasn't much Cajun music in this area and there still isn't. So if I was trying to make a living as a Cajun musician today I couldn't do it, but because I did it when I did, I was able to stay employed as a fiddler for 27 years. Now I'm easing out of being a performer and focusing more on becoming a teacher, doing workshops, and private lessons. In Cajun music today I think there is too much loudness, it's too much like rock. The loudness has its place, I suppose, but I'm a traditionalist, and my students come to me because of that. I prefer the acoustic sound.

Country Music

Louisiana has made major, national-level contributions to the evolution of country music. Shreveport typically gets the most credit and attention for such activity as the home of The Louisiana Hayride, a live-performance country radio program broadcast weekly from 1948 to 1960.

Country music has long maintained a devoted following all across the state. Significant folkloric fieldwork on various country styles has been conducted in both Louisiana's Florida parishes and Delta parishes. The tradition of community-centered live performances continues today. In the small St. Tammany Parish town of Abita Springs, for one example, the Abita Opry presents six performances a year, with country figuring prominently in the programming. July finds the annual Louisiana State Fiddle Championship underway in Natchitoches, in Natchitoches Parish.

And, for some two centuries, the musical tradition now known as country has maintained an important presence in the Livingston Parish town of Denham Springs. This presence dates back to the westward expansion of the early 19th century, when Anglo-Americans first began to populate the region bringing various British-based folk-music traditions with them. By the 1920s, such sources had melded with popular commercial sounds and ethnic influences—including a strong African-American component—and were marketed as "hillbilly" music, a term considered offensive today. By the mid-20th century, this synthesis came to be called "country music." Today, country styles ranging from classics of the 1950s to the latest commercial hits are often heard in Denham Springs and its environs (Seelinger 1989).

-

In this essay, "Creole" refers to the members of southwestern Louisiana's black community who speak French or have ancestors who did. This definition of "Creole" is one subjective usage among many other interpretations. Such differing perceptions often spark strong disagreement in Louisiana.

-

In business continuously since 1934, the Famous Door nightclub is said to be the oldest operating music venue in New Orleans and is known for Dixieland jazz. The term Dixieland, which is not widely used at this writing, is synonymous with traditional jazz, and the traditional New Orleans repertoire in particular.

-

In 1971, Capone was a co-winner of a Grammy award for the Best Engineered Recording, non-classical, for his work on the theme song for the movie Shaft, written and performed by Isaac Hayes. The song was recorded at Memphis' renowned Stax Records studio.

-

Buddy Rich (1917-1987) was a renowned big-band jazz drummer. The popular crooner and TV host Andy Williams (1927-2005) was known for such classics as "Moon River." Burt Bacharach (b. 1928) is a prominent popular song composer who often collaborating with lyricist Hal David (1921-2012) on hits including "Always Something There To Remind Me." Bob Hope (1903-2003) was a world-renowned comedic film star, beloved for performing for American soldiers in war zones. The acclaimed pop-jazz crooner Tony Bennett (b. 1926), of "I Left My Heart in San Francisco" fame, remains in peak form at this writing (January 2017).

-

During the 1930s and '40s, trombonist and arranger Glenn Miller was a leading proponent of the jazz style known as big-band swing. His acclaimed colleague, clarinetist Benny Goodman—nicknamed "The King of Swing"—was also respected as a pioneer in leading racially integrated jazz bands, then considered socially and politically radical.

-

"The Rat Pack" was a loose aggregation of singers, entertainers, and films stars led by Frank Sinatra (1915-1998), Dean Martin (1917-1995), Sammy Davis Jr. (1925-1990), Peter Lawford (1923-1984), and Joey Bishop (1918-2007). Their heyday was the late 1950s–mid-'60s. The Crosby Brothers—sons of the famed crooner Bing Crosby—were a popular vocal quartet active in this same era. Actor Richard Conte (1910-1975) appeared in Ocean's 11; actress Sheree North (1932-2005), was not in the film. Nor were the major movie stars Elizabeth Taylor (1932-2011) and Eddie Fisher (1928-2010).

-

The jazz guitarist, banjo player and singer Danny Barker (1909-1994) was also an acclaimed raconteur and memoirist whose books include A Life In Jazz.

-

Coco, whose musical friends also included Pete Fountain, chronicled his life in the book Blessed Be Jazz: The Story of My Life As a Clarinet-Playing Jesuit Priest in the French Quarter of New Orleans.

-

The statue was eventually moved to Armstrong Park.

-

Unfazed by socio-political criticism that the lyrics to "When It's Sleepy Time Down South" perpetuated racist stereotypes, Armstrong recorded the song nearly one-hundred times throughout his career, creating a revenue stream of composer's royalties for Leon René and the other co-writers.

-

WLAC could be heard widely around the American South and Midwest, and its influence in disseminating blues is cited by many musicians, from a variety of genres, who came of age in the 1960s.

-

Another name for the vinyl "single," with one song on each side, the 45 was so named for its play speed of 45 rotations per minute (rpm).

-

Many Cajuns and Creoles shunned their ethnicity from the early 20th century into the 1960s. There was considerable pressure to do so, as exemplified by a 1916 state law that forbade the speaking of French dialects in Louisiana's public schools.

-

A scholar of mythology and comparative religion, Joseph Campbell offered this mantra in his books.

-

See Campion 2014 for a discussion about Mardi Gras symbolism.