African-American Quiltmakers in North Louisiana: A Photographic Essay

Essay and photos by Susan Roach

Introduction

As I researched traditional quiltmaking in north Louisiana for my dissertation, I found I needed photographs of quilts and quiltmaking techniques to document technical, formal, and aesthetic concerns of the quilters; consequently, I photographed these women in various stages of quiltmaking and with their quilts. Finding photography to be an easy method of record keeping, I photographed the quiltmakers with their quilts in their homes and in some cases at special events. After my dissertation, I continued documenting quiltmakers when the occasion arose.

Looking back at these photographs, I was struck by the power and dignity of these women, who had chosen the difficult, time-consuming expressive mode of quiltmaking. As documents of their patience, perseverance, and creativity, the quilts also reflect the nurturing, work-filled lives these women have led, living through the Great Depression in the country and city. Sadly, many of these women have passed on; yet their quilts stand as a memorial honoring them.

The photographs here, taken between 1979-2001, provide a sampling of traditional Louisiana African-American quilters and quilts. To complement the photographs, I have also drawn from my interviews with these quiltmakers, so they may speak for themselves. I have chosen photographs to illustrate not only the women's techniques and types of quiltmaking but also issues raised by contemporary scholars of African- American quilts. A brief survey of these issues provides a sense of the research context in which the initial photographs were taken and the evolution of scholarship on the topic.

Traditional Techniques and Quilt Types

Examination of the photographs of the steps and the variations in those steps of the complex technical process of quiltmaking yields insight into the quiltmakers' aesthetic visions. The learning process of traditional quiltmaking parallels that of other folk arts, in that a few directions are given now and then, but generally the pupil learns by watching and imitating. Quiltmaking, like any folk art, requires a degree of technical ability. Competence in the craft involves not only the learning and practice of skills, such as color coordination, cutting and arranging patterns, piecing, and quilting but also the acquisition of knowledge of local standards and acceptable modes of creative expression. Most of these quilters learned quiltmaking basics between the ages of four and fifteen from mothers, grandmothers, and neighbors; then depending upon their interest in the craft, they developed their finer skills.

Traditional techniques used by the quilters vary. While a few women piece their tops all or partially by machine, most prefer piecing quilt tops, especially their fancy patterns, by hand because each corner of each piece can be aligned carefully and because of the relaxation provided by the activity. After the top is completely pieced, the top must be joined with the insulating layer, termed "batting," and the bottom layer of fabric, termed "lining." The three layers are usually sewn, or "quilted," together with a running stitch through all layers; however, they can also be quilted on the machine or tacked (also termed "tying" or "tufting"). Quilting may be done on frames which may be set on stands (termed "horses") or hung with rope or cord from the ceiling so that the frames can be raised up out of the way when not in use. While African-American quilters do use frames, many do their quilting on the bed. Quilting on the bed is more commonly found among African-American quilters than European-American quilters in north Louisiana.

Louisiana quiltmakers' skills and experience and their quilt types have a wide range, from utilitarian quilts (termed "common" or "everyday") used for simple bedcovers to decorative ones ("fancy"), used for special occasions, gifts, competitions, or heirlooms. These labels originate in the quilter's degree of skill, her intended use of the quilt, and the amount of care and work put into a specific quilt. Some women have made only one or two quilts which may be of excellent or mediocre quality depending on their sewing skills; some make only "common" (or "everyday") quilts for cover; some make both "common" quilts and "fancy" quilts; and still others spend their time only on "fancy" quilts. The quilters' distinction between everyday and fancy quilts is an important aesthetic element, which has great bearing upon their quilt production.

However, most studies of European-American quiltmaking have considered only fancier creations, rather than utilitarian quilts. Scholars and quilt revival enthusiasts have characterized European-American quilts as being carefully color-coordinated, symmetrical, impeccably pieced, and quilted with tiny, even stitches--elements common in the fancy quilts found in north Louisiana. Based on this, scholars have often contrasted European-American fancy quilts with African-American everyday quilts instead of examining the same type quilt for each group. Quilters in north Louisiana do produce quilts which follow the European and African-American quilt norms; however, many of the region's quilts, especially those designated for everyday use and those made in lower socio-economic groups, are not such clear cut examples of these norms.

African-American Aesthetics

In addition to examining quilts for differing aesthetic standards suggested by technology and type, scholars have also researched the ethno-aesthetic variations achieved through patterning. Over the past thirty years, a stereotype of "African-American quilts" has dominated the market in spite of objections by some folklorists and African-American quilters and quilt researchers (Mazloomi 2002; Freeman 1996). Theories of Vlach (1978) and Wahlman (in Freeman 1981) initially developed what would become the stereotypical African American quilt, exemplified in the popular exhibition, The Quilts of Gee's Bend (Beardsley). According to their theories, African-American quilters learned to produce quilts reflecting the European-American aesthetic, but preserved African aesthetic principles by selecting and improvising on American quilt patterns that were similar to African textile designs, such as strip weaving from western Africa. Vlach (l978) finds African analogs for the appliqué quilts of 19th century quilter Harriet Powers in the Fon tribe and other African appliqué textiles. Similar analogs for "string" or "strip" quilts commonly made by black quilters can be found in the strip weaving occurring in western Africa. Vlach (l978) and Wahlman (1983) cite a number of design elements typical of African-American quilts: the use of strips to construct and organize the surface, large-scale patterns, high contrast (or high affect) colors, off-beat patterning, unpredictability, improvisation, and multiple rhythms.

Another scholar, Eli Leon, expands upon this research, looking for significant African influence on American quilts. Drawing upon the history and prevalence of improvisational patchwork in Africa, he suggests that African slaves in the U. S. and England may have been more familiar with patchwork and improvisation than their masters. African artisans may have drawn upon this knowledge to develop many of the quilt patterns, which could have been noticed and adopted by European-American quilters (Leon 59-61). Leon cites the following characteristics of "Afro-traditional" quilts: "Structural flexibility, improvisation, approximation, technical accommodation for off-sized pieces, use of string pattern, strip construction, allowance of accidentals, multiple patterning, complex alternation, restructuring, use of leftover patchwork, and patchwork on both sides of the quilt" (63). While these qualities can be found in many African-American quilts, they can also be seen in some north Louisiana European-American quilts, especially those "everyday" quilts made by women in lower socio-economic groups (Roach 1986). While the quilts of the two ethnic groups in the region may exhibit some differences, some features are found more often in each ethnic group. Of the characteristics attributed to African-American quilts in earlier studies, unpredictability and improvisation are the most prevalent in this sample.

Although research has not proven, and perhaps cannot prove, what group first produced patchwork such as improvisational strip quilts and the "Log Cabin" quilt pattern, we can see the manifestations of these qualities in some European-American quilts and many African-American quilts such as those of this group of Louisiana women.

The question of the African-American preference for different styles of quilts such as the strip blocked quilts and strip quilts is not so simple, however. In regard to the strip quilt, cited in previous studies as an aesthetic preference of black quilters, it is not a favorite of most of the quilters in this sample. The women such as Rosie Jackson who still make strip quilts actually aesthetically prefer more intricate patterns. Many of the quilters have made and used such strip quilts in the past. These quilts were inexpensive in materials and labor, easy to construct, and durable, making them a good solution to the need for long-lasting everyday bedcovering. Today, the strip quilt is being made by only a few African-American women and still fewer European-American women; however, it is an important part of the historical backgrounds of most of these rural women in the region since it provided efficient warmth for cold winters in houses heated only by wood stoves and fireplaces. The need for such everyday quilts lessens as the production of these common quilts dwindles; however, the desire to make fancier, decorative and art quilts is growing, following the national trends cited in Mazloomi and Freeman's research.

With the development of better technology for heating homes and more leisure time, the strip quilt is being forced into the aesthetic background, overshadowed by more intricate patterns. Since the quiltmakers first learned to make the simple, everyday strip and string quilts before they learned the more complex patterns, the strip quilt is also in their developmental backgrounds. This developmental history is apparent in their quiltmaking histories. Because of the region's quilter's common backgrounds and their production of both everyday and fancy quilts, distinguishing any ethnic difference among European- and African-American quilts is difficult. However, more importantly, allowances must be made for the creativity of the individual quiltmaker and her aesthetic judgments.

The Quilters and Their Quilts

Annie Lee Morrow

Annie Lee Morrow (1925-2003), of Dubach, in Lincoln Parish, does her piecing of quilt tops by hand at night while she watches television. When asked how she decides which colors to piece together, she explains: "I would just try to match them, to keep from putting two red pieces together . . . You just have to use your own judgment about it. Now when I was first started quilting, I would just lay mine [squares] down and see which would match this piece and put it down there and maybe I'd have something else that would match the other piece and put it down there. . . .My mother would always say `Don't put the same colors together all the time; just mingle them up, and that makes it look pretty.' So that's the way I would do." The term "match" used here means coordinate colors rather than the same colors.

Since most traditional quiltmakers first learned to make the simple, everyday strip and string quilts before they learned the more complex patterns, the strip quilt is also in their developmental backgrounds. Metaphorically portraying these levels of development, Annie Lee Morrow's "Star" quilt (1978) based on an Anglo-American pattern, which she copied from a book, is backed with a stripped lining, identical to the stripped tops on strip quilts. Although she made quilts with strip tops in the past, today the strips have become the lining, the backing. This quilt then serves to illustrate the evolution of quilt production and form.

Deola Jackson

Deola Jackson, of Natchitoches, demonstrates quilting on a "String" quilt at the Natchitoches Folk Festival. She also usually quilts alone, but likes working on a frame in order to stretch the top tightly over the lining. Her "String" quilt is a typical flexible pattern used by many north Louisiana quilters to take advantage of leftover small strips of fabric, which are stitched together diagonally to form a block. Note that she sometimes alternates the direction of the diagonals in adjacent blocks and sometimes the diagonals go in the same direction.

A Lake Providence Senior Citizen's Center

A Lake Providence Senior Citizen's Center provides the context for group quilting bee. Gathered around a traditional quilting frame set on "horses" to quilt are (from right back, clockwise) Rosie Lee Love, Laura Thompson, Mary Davis, and Mrs. Edward Jones, and Georgia Edwards. Today, the quilting bee is no longer a common neighborhood or family occurrence, but instead is usually organized by agencies such as senior centers and occasionally churches.

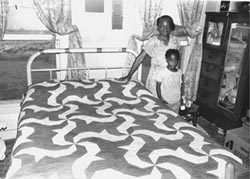

Rosie Lee Allen

Rosie Lee Allen (b. 1929), of Homer, in Claiborne Parish, quilts her "Nine Patch" quilt on the bed, even though her mother quilted on frames. While she used to make strip quilts, now she would "rather sit down and do something fancy," such as the "Star," "Around the World," or "Dresden Plate" (below). In the bed method of quilting, the lining is spread over the bed, the batting is then spread over the lining, and the pieced top is laid over the batting. The edges are rolled under until the quilter is ready for that section. Because bed quilting cannot stretch the layers the way frames do, the quilt may appear less smooth and rigid. This method is frequently used when space in the home is limited. Such houses also call for creative storage of quilts and quilting materials in such spaces as the top of a wardrobe as Mrs. Allen does here. As many other African-American quilters, Mrs. Allen quilts most of her quilts in "rows," which are decreasing concentric half squares, similar to the traditional "shells," which uses decreasing concentric half circles.

Mary Anderson

Mary Anderson (b. 1917) of Alexandria, in Rapides Parish, reports that the typical quiltmaker now quilts alone rather than working in a quilting bee: "No, we don't get together and quilt. . . .We used to do that years ago, put in a quilt and give a quilting and have coffee and teacakes and something to serve. People don't do that no more. Everybody just quilts their ownself." Having made several traditional "Flower Garden" and "Honey Comb" quilts using hexagons, she took some extra hexagons, stitched them together in clusters and applied them to the solid gray background to make this improvisational quilt. In quilting this quilt in 1980, she decided to quilt in "little rows" (one-fourth inch apart), a decision which caused her to "worry her brains out" because it was taking so much time and attention.

Charlotte Thomas

Charlotte Thomas (b. 1928), of Alexandria, the sister of Mary Anderson, was also taught to make quilts by her mother Mary Price. One of her earliest quilts she made was a large-scale strip quilt, but later she preferred to piece traditional patterns such as the "Star," "Honey Comb," or more detailed string quilts such as this one (made 1979), which improvises on the "Log Cabin" pattern.

Rosie Jackson

Rosie Jackson (1900-1990), of Chatham, in Jackson Parish, in her later years did most of her quilting on her "common" strip quilts on the machine or by tacking. The center quilt made of dark blue, wine, and brown solid heavy fabrics, is tacked with multi-colored embroidery thread, while the left and right quilts are quilted by machine. Basically, the strip quilt is constructed of cloth strips of varying widths and lengths, usually four to twelve inches wide and one to six feet long. These strips are sewn end to end and side to side until the fabric is large enough to cover the bed.

Strip Quilt: In describing how she made this improvisational strip/patchwork quilt, Rosie Jackson said that she made the blocks first and then, "I just studied about a way to fix it up and put it [the blocks] in the center and put the strips around it. I was just studying a way to fix it; I wasn't studying nothing fancy." This quilt and her approach to it reflect many of the characteristics noted by Leon, including flexibility, improvisation, approximation, technical accommodation of off-sized pieces, string and strip construction, multiple patterning, and use of leftover patchwork.

Cloaner Smith

Cloaner Smith (b. 1913) of Lisbon, in Claiborne Parish, calls this strip quilt a "String" quilt which she just "builds up." The large scale design, reminiscent of the small scale "Log Cabin" pattern is pieced in cotton factory remnants of red/white, brown/white, and lavender/white prints and quilted in rows (compare with the smaller blocks of Jackson's quilt in figure 7). Continuing to quilt into her later years, she remembers her first sewing experiences imitating her mother and her mother's response: "I've been quilting since I was old enough to sew. My mother always done that. And I was a nosey little old girl, and I always stood in the way. Every scrap she'd drop, why, I'd pick it up and sew. I kept sewing until I got where I could make a good block, and she put it in her quilt as encouragement."

Rosie Whaley

Rosie Whaley (1903-1990), a prolific quiltmaker of Pine Hill community in Claiborne Parish, remembers this special improvisational quilt (a "Four Leaf Clover" with red motifs appliquéd on bright blue background) that her mother, Agnes Sims, made for her one Christmas. Mrs. Sims sewed too long in an attempt to finish the quilt as Mrs. Whaley recounts the narrative:

She pieced this one [quilt] until knots come on her arm, trying to get it by Christmas. I said, "Mama"--she was showing me [the quilt]. "What's that?" [referring to the lumps on her mother's arms]. She said, "Quilting, honey." I said, "Mama, you ain't got to quilt that hard." I said, "Quit, we can keep warm; if we ain't got enough cover, throw coats on you." She said, "I'm trying to get it through to give you for Christmas. I got all the rest of the gals one." She went on and worked with it until she got it through. Mrs. Whaley's appreciation for this quilt, which caused her mother such problems is evidenced by her saving rather than using the quilt.

Rosie Whaley pieced and quilted numerous strip and "Around the World" quilts from polyester knit fabric, a favorite during the 1970-1980s period, which exhibits improvisation and multiple rhythms.

Josie Shelton

Josie Shelton (b. 1917), of Haynesville, in Claiborne Parish, produced an accidental variation of the "Drunkard's Path" quilt, when she inadvertently pieced the pattern differently from the traditional one—which Leon terms "allowance of accidentals" (63). She knew that she had not pieced the pattern exactly as it should have been, but it fit together, and she liked the new pattern she had created, so she left it. The quilt exhibits the high-contrast colors of red and yellow, careful piecing, and quilting by the piece. Josie Shelton also makes everyday quilts for cover, using leftover blocks, strips, and large pieces of fabric, which look strikingly different from her other "fancier" quilts.

Leola Simmons

Leola Simmons (b. 1909), of Downsville, in Union Parish, displays her polyester version of the popular "Trip around the World" pattern, which typically is carried out with each concentric row a squares using the same color; this row is then attached to a different colored row. Note that around the edges, she attempts to stay with the same color square on each row, but resorts to multi-colored rows inside since she did not have enough of the same color fabric. While she does not try to control the color scheme, she does exert control over the top through her careful piecing of each square, where each corner meets the other precisely.

Essie Intoe

Essie Intoe (b. 1909) of Chatham, in Jackson Parish, like many quilters periodically hangs her quilts on the clothes line to air them. The last quilt on the line exhibits stripped blocks, a common technique in African-American quilts. One of her favorite quilts is the traditional large scale Euro-American design, the "Lone Star," which she has made several times, often with bright high contrast colors such as orange-turquoise or red-white combinations. She frequently quilts such quilts "by the piece," going around each diamond, but in the large corner squares, she quilts in rows, just as she does on her stripped baby quilts, which she began making by commission on request.

Frances Sykes

Frances Sykes (b. 1897 deceased) (left), of Claiborne Parish, proudly displays one of her many fancy quilts, a "Broken Star," precisely pieced with reds, pinks, blues, and white and quilted "by the piece" with tiny stitches. She recalled the first time about age twelve that she was permitted to help with fancier quilting "by the piece" on her mother's frames:

I asked her, "Mama, let me quilt one of those." She said, "I don't want you messing with my quilt." And I said, "Now I'll set down right here and quilt right at the first block." So I began at that block and got the block quilted. Mama rolled that quilt up that night and said, "Look up there." And that just tickled me.

I said, "Mama, nobody'll know who quilted it." Her comments reveal the importance of the bonding of mother and daughter through the medium of the quilt and the pride these women take in carrying on their African-American heritage.

Emma Russell

Emma Russell (1909-2004) grew up in Mississippi, but moved to Louisiana, after she married, settling eventually in Friendship in Bienville Parish. She learned quilting from her grandmother and mother, Phoebe Johnson. Recalling how they prepared the hand-picked cotton to make the batting then, she says, "They would take a stick, and cut the prongs off, and put a pile of that cotton in the middle of the quilt. And sometimes those ladies picked the seed out and started beating it with that stick, and it'd get so fluffy, and they would beat that cotton all over that quilt." While she made many original narrative appliqué quilts based on Biblical scriptures and her life on the farm, she also pieced and appliquéd many traditional designs as well, such as those in this "Golden Wedding Ring" quilt top, exhibited at the Bienville Depot Museum in Arcadia in 2001. Her quilts, along with her mother's, are featured in Roland L. Freeman's A Communion of the Spirits: African American Quilters, Preservers, and Their Stories and touring exhibition.

Sources

Beardsley, John, et al. The Quilts of Gee's Bend. Atlanta: Tinwood Books, 2002.

Leon, Eli. Who'd a Thought It: Improvisation in African-American Quiltmaking. San Francisco: San Francisco Craft and Folk Art Museum, 1987.

Roach, Susan. The Traditional Quiltmaking of North Louisiana Women: Form, Function, and Meaning. Diss. University of Texas at Austin, 1986. Ann Arbor: UMI, 1986.

Freeman, Roland. A Communion of the Spirits: African-American Quilters, Preservers, and Their Stories. Nashville: Rutledge Hill Press, 1996.

_____. Something to Keep You Warm. Jackson, MS: Mississippi Department of Archives and History, 1981

Mazloomi, Carolyn. Spirits of the Cloth: Contemporary African American Quilts. New York: Clarkson Potter/Publishers, 1998.

Roach-Lankford, Susan. Patchwork Quilts: Deep South Traditions. Alexandria, Louisiana: Alexandria Museum, 1980.

Roach, Susan.The Traditional Quiltmaking of North Louisiana Women: Form, Function, and Meaning. Diss. University of Texas at Austin, 1986. Ann Arbor: UMI, 1986.

Vlach, John Michael. The Afro-American Tradition in Decorative Arts. Cleveland, Ohio: Cleveland Museum of Arts, 1978).

Wahlman, Maude Southwell. "The Aesthetics of Afro-American Quilts." Something to Keep You Warm. Jackson, Miss.: Mississippi State Historical Museum, 1981.

_____. Afro-American Quilters. Diss. Yale University, 1983.