Table of Contents

Folk Regions

Three Ethnic Perspectives

Folk Music of the Florida Parishes

People of the Florida Parishes

In Retrospect

From Country to City: Blues in the Florida Parishes and Baton Rouge

By Ben Sandmel

The Florida Parishes are a rich repository of traditional Black music and culture. Several physical factors support these conditions. The area is mainly rural and agricultural, and in some places quite isolated. What's more, a significant number of settlements, such as Solitude in West Feliciana Parish, are entirely Black in population. (There are also many all-white villages, such as Talisheek in St. Tammany Parish.) In addition, during the height of the timber industry, there was a long-standing tradition of turpentine and lumber camps with resident Black male workers. These factors all point up the existence of a close-knit folk community which supports both blues and gospel music.

The Florida Parishes also include the blues-rich city of Baton Rouge and lie adjacent to the state of Mississippi, a traditional blues stronghold. While blues probably evolved simultaneously around the South, Mississippi emerged as an especially dominant source region. This was due in large part to the state's plantation economy. A concentrated and strictly segregated work force kept the system functioning, and produced—along with cotton—an extensive and heavily African-retentive music scene. For the most part, though, there was no comparable concentration of labor in the Florida Parishes with proportionately less music as well. It seems significant that the blues performances recorded in Florida Parishes fieldwork lean heavily on the commercial recordings of such prominent Mississippi blues artists as John Lee Hooker, Jimmy Reed, and B. B. King, as opposed to original material.

In fact, most of the blues being played today in the Florida Parishes comes from just such commercial, post-War recordings, with a corresponding pattern in gospel music. Many talented and authentic musicians may be found, both secular and sacred, connected to the Florida Parishes, and their presence indicates an extensive, supportive community.

One such musician is the Reverend Elijah Ott, who has been involved with the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival as a gospel music consultant. As a former resident of Kentwood, Ott is well-connected with both blues and gospel musicians throughout Tangipahoa Parish. While glad to give information on blues performers, he has strong opinions about the incompatibility of such music with a truly religious lifestyle:

To me there's two kinds of music. You got one for God, and one for the devil. A lot of people think otherwise, but that's just the way I feel about it! I always sing to God, 'cause I always want to be with him.

Gospel-blues antipathy is an important concept in traditional Afro-American culture. Quite a few blues musicians, including Louisiana guitarist Lonesome Sundown, have resolved the conflict by forsaking blues and joining a church. The issue has also inspired such classic recorded performances as Edward "Son" House's "Preachin' Blues."

While the Reverend Ott's gospel music is essentially contemporary, although traditionally rooted, his cousin Zack Carter is about as traditional as they come. Carter's limited guitar skills relegate him to a non-professional, "front-porch" musician status. A former Florida Parishes resident, by 1984 he had moved just across the Tangipahoa Parish line into Mississippi, and his highly rhythmic approach is typical of the area. He performs both sacred and secular material, yet maintains that blues are evil:

Blues music is the devil's music, because if you listen at blues music, blues music will give you all kinds of thoughts in your mind—ideas. If you be listenin' at music, folks might be walkin' with a stick, and the right kind of music, you'll throw it down. All music rolls just about the same way—music is good anyway you take it. If a bluesman likes blues, it's good to him, if a church man likes church music, well, that's good to him, it's just a rollin' thing. And I don't care what kind of music playin', when it start, someone gonna start pattin' they foot. That's music. Music has got the same wheel, ain't nar' another wheel to music but just one wheel, it just different tunes and different feelin' 'mongst the people.

Otheneil Bridges, Sr., of Hammond is a facile singer and talented guitarist. His repertoire concentrates on such post-War blues recording stars as Freddie King, Guitar Slim, Lowell Fulsom, Lightnin' Slim, Ray Charles, B. B. King, Junior Parker, and Jimmy Reed. At times Bridges is quite slick and urbane, but his most emotional performances recorded are gospel tunes which reflect a far more raw and old-fashioned Mississippi Delta approach.

Bridges has worked as a full-time musician. But because of recurrent cultural conflicts surrounding religion, Bridges never recorded professionally. In 1969, he stopped playing blues in public and now performs in church only. While quite willing to demonstrate his blues skill in an interview, he stated at the time that public performances were a thing of the past. A year later, however, he relented long enough to play a strong blues and gospel set at the River City Blues Festival in Baton Rouge.

Bridges' interview is notable for succinct, eloquent remarks:

I was born in New Orleans in 1938. Ever since I was a real small kid, crawlin' around on the floor, my uncle had an old guitar layin' on the side of the wall, and I'd pull it down on the floor and bang on it. I guess I've always been musically inclined. After I grew up I always wanted to play a guitar, but I never had the opportunity. In elementary school, McDonough 24, we had a band teacher, and I played clarinet, and tenor sax, but I never did like a horn. Then my daddy bought me an upright piano for ten dollars, and I'll never forget he helped me carry it across a brand new rug that we'd put down in the front room. But I didn't like piano, I always wanted to play guitar. There was a guy used to come around, he could kind of hit a note or two, and he was sitting out front. Now my parents didn't want me to play the blues, period. My parents are religious, mainly my mother, and they look at it as the Devil's music. That kind of held me back, but every chance I got I'd get out there and just play what was in my head. My mother was over-protective, and if she missed me ten minutes, well, she'd come lookin', and that evenin' she heard the guitar goin' over at this guy's house and she followed the sound and come over and got me. That was kind of embarrassing, but if you're still at home you got to do what they say.

Bridges grew up during the "Golden Age" of New Orleans rhythm & blues, but such music made little impression on him. "I was always a blues man. I never cared for Fats Domino. I never did like rock. If the song said blues then the strings had to say blues, for me. You just got to hit what's in your mind, hit what you're feelin'."

While it may seem unusual that an urban teenager would maintain such a pure blues sensibility in the midst of New Orleans' rich music scene, Bridges offered an articulate explanation:

Folks in certain places, they like sentimental music, they like soft music, they like rock. Well, fine, but when I stepped in with my back-behind-the-corn-crib blues, well, they know where they come from! So they join in, you know. They get back behind the corn crib with me, because they liked it. I mean 90 percent of the people in New Orleans are from Mississippi anyway (as are Bridges' parents) so they're country people. They went to the bright lights and got wild, but deep down within they got that back home feeling neath that skin. They got it. So if someone can come along and pull it out of 'em, well, they'll react to it, and that's what they did. That's what they wanted to hear.

Apart from the previously mentioned neighbor, Bridges had little personal instruction:

I learned from records on jukeboxes, and one of the first was Jimmy Reed. That just caught my attention real good, and so I hung into that, but finally I realized that all of his music was just about the same. . . . So I tried 'em all, John Lee Hooker and that "Boogie Chillun," and then "Hobo Blues." And that was fine, but it still didn't excite me. Finally at last Albert King and Freddie King come on the scene. And oh, I can't forget old Lowell Fulsom.

He waited until leaving his parent's home, before performing:

So I finally got married, and I thought I'd try it all out, and, well, I did. I'd play at Claiborne and Toledano, at the Banana Inn on North Peters, down by the riverfront. I played at the Ponderosa, on Felicity and Magnolia, I played at Angelo's, on Fourth and Danneel. I played at another little old lounge right across on Washington and Danneel. It was two places right across from each other. I'd play one in the evening time and one at night. This was in 1959. At that time the fans called me Guitar Slim, from that record "Things That I Used To Do." I left New Orleans in '62 and moved out to Amite. I never did like the city from the beginning, I just got tired of it, and then I started to have children. . . . So I moved out here and got myself a guy, well it was several of us used to get together, a guy by the name of Leatrice, used to play that old Elmore James stuff, with his pocket knife or antiseptic bottle, but with me he would mostly blow harp. Then sometimes I'd rest my hands and harp, and someone else would play guitar. I don't fool with harmonica now, but I can play it. I'm not a drummer either, but I can keep time til the drummer get there. When we was playin' we'd always swap around. . . .

My drummer was Carson Poindexter, from Velma, Louisiana. I think he's in New Orleans now. He's probably playing for somebody now, still. I met him and we come to be real close friends. And so I would sing and pick guitar and he'd play the drums. If I'd make a mistake, well, couldn't nobody hardly tell it no way, cause I could pretty much cover up my tracks, if I was to make an error. Once the people felt that you are it, you don't make mistakes—I've gone in places where people say I wasn't 'sposed to go, cause of the environment, rough places, I'm a stranger comin' in there, and they don't know me, and I just walk in, well, I let my guitar do the talkin'.

Then as time rocked on, that record come on there, "Hideaway." Playin' that "Hideaway," everybody started callin' me Hideaway Slim, because they had never heard it played really close to the way Freddie King made it. He was a guy that I liked to pattern myself behind some of his songs. And I just put nickels, dimes, and quarters in jukeboxes until I just got "Hideaway" down pat, and I received the name Hideaway Slim.

I took care of my family with my guitar, playin' sometimes four nights a week. Sometimes I'd double up on weekends. Sometimes, I'd play three times on Saturday. At the time, the bars never closed. It was a twenty-four hour deal, and I could start around eleven in the morning on Saturday, and play a gig, and then that night I'd play another. They'd bill me as Hideaway Slim—that's the way they'd put it out. I had an old '48 Chevrolet car and I painted all around the side there ‘Hideaway Slim.’

Bridges did not say exactly what prompted him to quit playing and join the church, but even as a full-time musician his religious training kept him from making records or pursuing his career to the fullest:

It have been people come to my house to sponsor me, to make records, to go to New York. When I was playing in New Orleans, before I left there, when I couldn't play nothing' like I did when I quit playin', and also since I have been here, I've had offers but I turned them all down on account of my training. I'd go to the fence but I never would cross it. In a manner of speaking, I'd run right up to the fence of opportunity, success, whatever you'd call it, but I guess it was just something that my mother taught me, that it wasn't right, that put a fear in me. You got to be out there all the way, you got to have your mind on what you're doing, you can't be half-cocked, thinkin' 'maybe I shouldn't go,' cause you're just climbin' a slimy pole—you're not going to make it. So if you don't go all the way, you might as well do like I did and let it alone, stay home and don't worry about it. I don't have any regrets either, I really don't. It's times it's crossed my mind that I could have had a Cadillac, or owned a home, but my mother's teaching was just enough to keep me from crossing that fence. I couldn't have did any worse. I don't guess I'd be in any worse shape than I am now—I say that, but I think I'd do the same thing over again. I wouldn't go. I could have had a better way of living, I guess, a big home, but my physical life, how would it have been? Music will age you. . . .

When interviewed in 1984, Bridges was working as a truck driver. His lifestyle was extremely modest, and though success had certainly been within his grasp, given his talent, his "no regrets" stance seemed quite sincere, calm, and centered. Not surprisingly, he did not disapprove of blues music as an option for others:

I love music. I love to hear someone that can take a guitar and play it. When someone can make it say something, on this side of the fence, or the other side, don't make no difference, as long as the guy knows what he's doing. I'll listen all night. I love guitar music, simple as that.

While Bridges' gospel repertoire seemed less extensive than his blues knowledge, one gospel number is truly memorable. Entitled "Don't Let the Devil Ride," it is based on a commercial recording by Brother Joe May, and is distinguished by a passionate vocal performance, some of Bridges' most traditional guitar work, and unique imagery which personifies the devil.

Don't, don't let the devil ride (twice)

If you let him ride, he'll want to drive

Don't let him ride

Don't, don't let him use your phone(twice)

If he use your phone, he gonna use it wrong

Don't let him ride

Don't, don't let him eat with you (twice)

If he eat with you, he gonna tell you what to do

Don't let him ride

Guitarist Daniel Ruffin of Independence proved to be an equally interesting and amiable character. A Black country-western singer, Ruffin grew up with traditional country blues:

When I was a little kid, my uncle would play like this: (plays a few bars of slow, Delta-type blues chords). I wanted to learn like that, but blues wasn't really my thing. That's all my uncle used to do, was play. He used to have an acoustic guitar, he'd play for parties, and clubs, family-type things, like when all the relatives would come around. His name was Robert Williams. I don't know if he made any records or not, but that's the type of music he played, and he started me off.

Soon afterwards, though, Ruffin was exposed to country music:

I was born and raised with country music. Out at our place in the country (near Wilmer, in Tangipahoa Parish) I used to help this white guy milk, and his dad could play a guitar. And he was playin' but he didn't know that I would listen on it, but I would sit and listen at it. But he didn't know that I was tryin' to get it, either. Since I been playin' I been tryin' to contact him. I'd like to walk up to him and play somethin' to him.

Ruffin can only explain his somewhat unusual country preference in terms of a gut-level reaction:

I fell in love with it then. I used to hear Hank Williams and all them, and I just started playin' it. I don't know today why I started playin' country music. I just love it. I could've played rock & roll. I have danced to it, but I wouldn't want to sing it. Country music just have a feeling, it brings back remembrance. Every one of Hank Williams' songs, there's something you can get from it.

What seems especially noteworthy in Ruffin's case is his complete disinterest in the traditional Black styles he absorbed as a youth. On request he can play tunes like Lightnin' Hopkins' "Mr. Charlie" or Jimmy Reed's "Hush Hush," but would much rather perform "The Old Family Bible," "Me and Jesus Got a Good Thing Goin'," "Those Wedding Bells Will Never Ring For Me," or "Is Anybody Goin' to San Antone?" Ruffin lived outside the South for roughly twenty years (he was born in 1937) and moved back in 1980. He works as a truck driver, though he was unemployed at the time of the interview. A soulful singer, in the Hank Williams/George Jones mold, Ruffin's burning ambition is a career in country music:

When Kenny Rogers was in Hammond, I wanted to ask him a few questions, how to get started in the field, you know, but them type of people you can't get to 'em. I was thinkin' of going to Nashville but it best to know somebody. A guy told me that I have the voice if I just practice and get myself together. I love country, I love it! This is where I stand now; I really want to go into it. The more I go out and play, I love it! I want to put it together and do something with it, this is my motto, what I really want to do.

Ruffin currently plays mostly in Black churches, where he's known as "Country" and, of course, plays country gospel. He plays some white churches as well, and claims to get an overwhelming response wherever he goes. Ruffin's comments on the secular-sacred issue have some peculiar twists, due to his country orientation, but also reflect prevailing Black attitudes:

I really didn't get into blues, because my father was a minister, and to him it was a wicked thing. I'll tell you about blues and gospel—everybody have they taste in music. This is the reason they made all type of music. Now they got your gospel, country-western, blues, they got your hillbilly, bluegrass, other words, they got all type of music. Well now all that music, ain't everybody got to like it. So this here the reason they have all this type of music. Now me, I love gospel, I love blues, I love country, but I love country more . . .

I was brought up in church, but when you young, long as you at home you gonna try to do what mother and father say, but when you get out you gonna lean out a little. Any young man gonna lean out. He might not stay out there too long, but he gonna try some of the world and see what it's like. . . .

I sing gospel in church, I separate it, I honor the church. If I'm at home I'm liable to pick up and play any old thing to get my music where I want it. I might sing some gospel at a bar, too, cause it's in me. . . .

My wife, she not too crazy about country, but she listen at it cause she know that what I do. She thinks it's blues, she think it's wrong by singin' it, she's religious. I told her, 'All music sound alike, it's people change the music. A C chord on a guitar is the same C chord in a church on a guitar. They changed it to make money out of it. It's people that change, the music is the same.'

Like Ruffin, blues guitarist Gus "Gatemouth" Cavalier of St. Francisville is a musician with enthusiasm. Mainly influenced by records, Cavalier's single-string, note blending style recalls early Albert King, and more specifically Willie Johnson, who recorded in Memphis with Howlin' Wolf. Cavalier is an excellent showman who synchronizes wild body movements with appropriate guitar licks. A farm laborer and bulldozer driver, he was asked to play at the annual St. Francisville Pilgrimage when local blues patriarch Scott Dunbar became ill. For interview purposes he set up a Sunday afternoon gig at a roadhouse called the Black Cat Club, on the road between Angola and Pinckneyville, Mississippi. Cavalier and second guitarist John Bennett Bell were playing through one small amp. While older patrons obviously enjoyed the music and shouted encouragement, the younger crowd set up shots at the pool table. During the break a one-armed disc jockey spun blaring disco records.

In his interview Cavalier talked about his early influences and former career and made some extremely witty comments about the blues and its "true meaning:

I learned guitar from my dad. We used to have house parties, like the Fourth of July, they used to call those old things collations (pronounced with the accent on the first syllable). This is when I was very small. They'd kill a hog, and eat him. They'd build a big platform, and call 'em collations. Everyone would eat and anyone who could play would bring an instrument and play. Back in those old days you had some good, good piano players.

I played by what I hear. If I hear a record that I like 'bout two or three times, then I got it and that's it. I been out of music almost twenty years, but before then we was playing everywhere—couldn't another band come into this parish, West Feliciana, and get a dance, cause we had it sewed up. At that time I was Gus ‘Gatemouth’ Cavalier and His Rockin' Aces. We was six pieces, two guitars, a four string bass, harmonica, and a tenor sax and an alto sax, which was seven pieces with a set of drums. We worked just about every night and then I worked days too, as a bulldozer operator. You can tell lookin' at my hands.

I been railroaded. I'm rusty, I just started back playin' for the Pilgrims (Pilgrimage).

I go down low as you go—I mean the lowest buttonhole, the low-down blues, and it gets good to me. I get happy. These blues'll getcha, you know. Blues means, like when you get up sometime, when you get out the bed, when you walk through the house, the floor don't feel right. You put your left slipper on your right foot and your right one on your left one, and behind that sometimes you stick your foot in 'em backwards! . . . That's the blues, that's what the blues is all about. But I love the blues. Sometimes it make you want to cry, you start thinkin' that you done went and spent all your money. Young people don't really understand the blues, all this head shaking and all that. What they playin' now in the bar, that ain't happening. But blues is comin’ back. Sometime it make me cry late at night. And I be singin’ when I'm on that big tractor, that engine goin’ hum, hum, hum, and I can holler the blues!

Two gospel music interviews point up the wide range of styles extant in the Florida Parishes, and the likelihood of a rich gospel scene. Big Anthony and the Sensational James Sisters of Roseland in Tangipahoa Parish sing in a polished, contemporary style. Many of their songs are secular pop melodies with superimposed gospel lyrics, and could hardly be considered folkloric. Nevertheless, the group is talented, and well worth hearing on its own merits. There are also hints of traditionalism in the emotional vocal delivery and use of such effects as falsettos and melisma (slurred and bent notes). The group's instrumental accompaniments are professional, studio-quality musicians.

At the traditional end of the spectrum, by contrast, is the Boliver Humming Four. This group takes its name from their birthplace, a small settlement in Tangipahoa Parish near Amite, where they are now based. Although the group has added a fifth member, guitarist Willie Joseph, they worked for thirty years in the classic a cappella format. "People thought we had music (accompaniment) but we was makin' it with our mouths and our hands," was founder John Brumfield's succinct description. Guitarist Joseph joined the group in 1963, and their sound today is that of an old-time group with guitar super-imposed. This has not, the group stated firmly, changed their sound. Leads are alternated, and the different voices are dramatically contrasted for maximum effect. Inevitably, though, it seems that some vocal dynamism must have been lost, as Brumfield unconsciously concedes: "When we had a quartet, every man had his own part; now, Willie can fill the spot of any man, with that guitar."

John Brumfield's account of the group's formation is intrinsically interesting in terms of content, and is something of an oral history gem:

The way we organized, one Saturday evening we decided we'd get a group of us together. Brother Pete, and R.C., and myself. We walked to Spring Creek, and Brother Rufe was up in the swamp, fishin'. It seem like today, when it come back to me. We called him like one of the disciples called Peter, called him off the creek bank and said come down here and meet us. We had a job for him to do and we organized right there on that bridge, fifty years ago this comin' August.

I called it to order, the first day we started out. We had a prayer service right there on the bridge, just the group. And then we began to get our rules together, that we was goin' to live by. The first and most important rule was don't let no girl or no bottle ever interfere with the group. If we be somewhere, early, sittin' around in the car before the program, if the girls come up to the car, get out! Don't never let no one-on-one be standin' around talkin'. If you in a bunch, laugh and talk and have fun, but don't take no seriousness to it. And if you drink, you don't sing. We didn't need you, regardless how good you was, cause we was gonna do this religious. I remember we said, 'Boys, we boys now, but we got to be men to do this job.'

I well remember when we sang our first church appearance in a program at Kentwood, at Sweet Home. Everybody got stalled for words, nobody could lead and there always got to be a break-off. And it fell my lot, and I remember singin' 'Where Jesus lead me, I'll follow.' And that's all it took. Now I wasn't a lead singer, but after I broke out Pete caught it, and tore house all asunder.

To get the full effect of these anecdotes, it is necessary to hear the group's inflections, Biblical allusions, and Willie Joseph's guitar chording in the background. Joseph himself is an almost hypnotic speaker, with his deep voice and laconic delivery:

I joined the group in 1963. I am the bass singer and musicianer. I started playing guitar when I was fourteen, in the state of Mississippi. I played cottonfield music. I didn't have education, but God gave me a gift. I used it in the way he gave it to me. I don't try to mark other peoples, I just do what the Lord put on my heart to do. I was born and raised in McComb. I used to sing with a group there, the Southern Stars. I moved to Louisiana and joined up with the Brumfield Brothers, the Bolivar Humming Four. It has been a great enjoyment to me. All these mens are Christian men. Believe in God. Believe in the right thing. And I just enjoy bein' a member of the Bolivar Humming Four. . . .

Yes sir, I played blues. Muddy Waters stuff, up there in Mississippi. House parties. I played with a slide. It was enjoyment to me then. I was young. I'd run over somebody to get to a house party to play. Lots of stump hole whiskey. Girls would set on my knee, boy, I was on top of the world! Then one day I found Jesus, and he converted me to gospel music.

The musicians and interviews described above represent the most fruitful rural blues-gospel fieldwork to emerge from the project. Of equal if not greater importance, though, is the rich music scene in Baton Rouge. The city's gospel traditions and resources have been researched by Joyce Jackson, and don't need to be discussed at length, beyond mentioning that they are considerable. One interesting note, however, is the perspective of the city's leading gospel singer, Reverend Burnell Offlee, of the Zion Travelers, on the blues-gospel conflict:

If you can get a direct message from a song, it really does something. Take these blues singers. They sing from direct experience, and those blues that they sing, they got the experience, they been through it, they know. Like some of 'em say, ‘If I don't find my baby, I'm gonna jump overboard and drown.’ Some people might do that, if they don't find that woman, they'll go up on a bridge, jump off and drown. But blues and spiritual music is just about the same, just different words. I don't see it as evil, cause you get a message out of it.

As a city with some decidedly semi-rural neighborhoods, Baton Rouge blues has, correspondingly, been a blend of country and city styles. Two of the city's most famous artists—guitarist/singer/songwriter Lightin' Slim, and harmonicist/ singer/songwriter Slim Harpo, both of whom are deceased—played in a rather relaxed, melodic style, distinct from both the heavier rhythmic emphasis of Mississippi and the aggressive sound of Chicago. One of Chicago's premier guitar stylists, Buddy Guy, learned his trade in Baton Rouge's clubs, and is certainly the city's leading alumnus. Today, however, there is relatively little local flavor in his music.

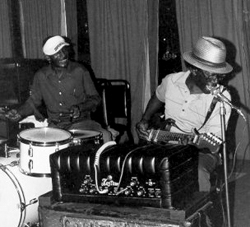

A capsule survey of the city's current performers indicates the stylistic breadth which can be heard, either on a typical weekend, or in concentrated form at the annual River City Blues Festival. At the rural end of the spectrum are guitarists Silas Hogan and Arthur "Guitar" Kelly. The two have been playing together for some twenty-five years now, achieving an intricate and intuitive rapport. Their informal, "front porch" approach is still sufficiently in demand to create several regular weekly gigs. Kelly and Hogan's repertoire includes originals, pre-War blues, post-War commercial hits, and occasional novelty tunes. This talented and entertaining duo perhaps best typify the country-city synthesis which influences Baton Rouge blues.

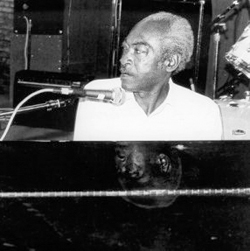

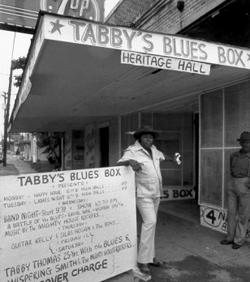

Several notable performers work more in a solidly post-War fifties vein. Guitarist/singer/songwriter Tabby Thomas has penned such often-recorded classics as "Hoodoo Party," and done important work as a grassroots cultural preservationist through his nightclub, Tabby's Blues Box. Pianist Henry Gray, a former sideman with the great Chicago singer Howlin' Wolf, has been based in Baton Rouge since 1968, working at times with Tabby Thomas and also fronting his own group on occasion. His repertoire includes boogie woogie, New Orleans R&B, and Chicago standards, and is not especially regional in emphasis, when compared to Thomas or Kelly or Hogan. Singing drummer William Woolfolk works in a down-home, post-War vein, drawing on the songs of such local artists as Slim Harpo. He is often accompanied by the fine city/country guitarist Clarence Edwards. Harmonicist Raful Neal is the leading local exponent of that venerable blues instrument. His style shows more of a Chicago/Little Water influence than a Slim Harpo/hometown sound. Neal is also somewhat of a blues community leader, and has encouraged several of his sons to pursue musical careers.

Neal's son, Kenny Ray, has emerged as one of Baton Rouge's leading young blues talents, although part-time residency in Canada has somewhat blunted his local impact. By contrast Tabby Thomas's son, Chris, has maintained a strong home-town identification. He is an extremely talented guitarist and songwriter whose style combines the traditional sound of his father with more modern influences such as Jimi Hendrix. In addition to these young heirs of blues dynasties, several other figures are well-worth mentioning. Guitarist Big Bo Melvin explores the contemporary, rather slick blues styles of recent years. This is only a small part of his extensive repertoire, which draws more on commercial, mainstream Black music. Guitarist Kenny Acosta is one of the many talented young white players whose interest has been a key factor in reviving the careers of many Baton Rouge blues artists, and bringing their music to new audiences.

In closing, a wide spectrum of blues and gospel styles can be heard in the Florida Parishes. The casual listener or fan has easy access to such music, while researchers will find a rich folk community which hosts many as yet unknown talents.