Table of Contents

Folk Regions

Three Ethnic Perspectives

Folk Music of the Florida Parishes

People of the Florida Parishes

In Retrospect

Music of the Black Churches

By Joyce Marie Jackson

It is commonplace to note that religion is a vital part of both Black-American history and today's Black community. Partly because Blacks were denied access to most institutions, the church became, after the family, the Blacks' most important institution, providing solace and solidarity, a positive self-image, emotional and spiritual release, and an experimental model for leadership. Blacks have taken a Euro-American institution--the Christian church--and reshaped it in significant ways to accommodate their beliefs, ideologies, and practices.

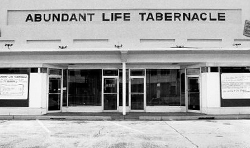

Black churches in East Baton Rouge Parish have been no exception, and there is certainly rich and diverse activity in these Black religious communities. Just as there are many different religious activities or practices, there are also many different types of church buildings. Church structures serving the Black community in East Baton Rouge Parish vary from storefront churches such as Abundant Life Tabernacle on Choctaw Drive, to modest middle-class church structures such as Mount Carmel on Swan Street, to imposing edifices such as Mount Zion Baptist Church on East Boulevard. As whites have fled to the suburbs, Blacks have bought many church buildings formerly owned by white congregations in the inner city. This holds true for the Greater New Guide Baptist Church on Fairfield Avenue.

Mount Zion Baptist Church, on East Boulevard, is a huge building considered to be the most upper-middle to upper class of Black Baptist congregations in East Baton Rouge Parish. Concomitant with its socioeconomic class makeup are the religious practices of the church. The religious services, for the majority of the time, are very rigid, although the pastor, Rev. T. J. Jemison (now president of the National Black Baptist Association) is strictly a product of the folk preaching tradition.

Folk preaching draws on traditional oral composition techniques. The sermon normally begins in prose and then moves into metrical verse. Rhythm and timing are among the most significant aspects of a Black folk preacher's chanted sermon. Intonational chanting is widely used by Black preachers to indicate inspirational climax in their sermons. This chanting is usually interspersed with moans, hollers, grunts, and shouts. The talent of the Black folk preacher can be evaluated according to how he renders the metrical lines while still delivering the message.

Although Rev. Jemison preaches in the traditional chanted sermon style, he seldom gets emotional feedback from his congregation. Again this is due to the fact that the congregation consists mainly of middle- to upper-class, reserved professionals. If someone does shout, it is usually an elderly person who grew up with that "old-time emotionalism" in the church, and is unconcerned about others reaction to self expression.

Music is of great importance throughout Black-American religion. At Mount Zion, however, it tends to be very rigid. The choir sings anthems, hymns, and arranged or concertized versions of the spirituals, interspersed with an occasional gospel song. Musical accompaniment is by organ and piano only. Occasionally, the minister decides, usually at the spur of the moment, that he will begin or end his sermon by lining out a song. Lining out is when the minister says one line of a song at a time for the congregation to repeat.

On the other hand, the Greater King David Baptist Church on Blount Road in North Baton Rouge (also referred to as Scotlandville) has retained more folk traditional practices than Mount Zion. The members of King David moved into a towering new structure in 1976. Although they now have a larger membership, with more professional congregants, the folk aspects of their church services remain strongly evident.

Rev. Isaac Warner preaches his sermons in the traditional chanted style described previously. The church choir performs gospel songs, for the most part, interspersed with an occasional anthem or arranged spiritual. The choir is accompanied by organ and piano. Occasionally they feature a guest drummer or saxophonist. The congregation is usually very verbal, enthusiastic, and tuned into what is taking place in the pulpit.

Another congregation that encourages response is the Fellowship Missionary Baptist Church. This church, founded and pastored by Rev. Gordon Craig, appears to be a cross between a Baptist and a spiritualist church. The music consists of gospel songs, and Rev. Craig preaches his sermons in the traditional folk style. Congregational shouting, religious dancing, and verbal interjections, like "Amen!," "Glory Be!," and "Praise the Lord!" are the order of the day. Glossolalia (speaking in tongues) and testifying are both prevalent at most services. So many congregants are shouting, dancing, and fainting that nurses are on hand to take care of them, and the congregation is very exhilarated. These practices, especially glossolalia, religious dancing and testifying, also take place in Baptist churches in urban Baton Rouge, but they are not as prevalent as in the spiritualist churches.

Many buildings used for religious services in urban Baton Rouge have been converted from other functions. Spiritualist congregations have sprung up all over Baton Rouge, meeting in buildings that once housed businesses, grocery stores, offices, and clubs. These storefront churches tend to have particularly lively and energetic services.

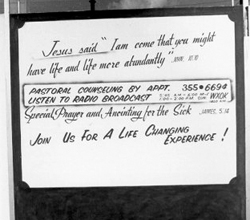

The Abundant Life Tabernacle in Baton Rouge, pastored by another folk preacher, Rev. Ralph Abernathy, has very enthusiastic services. The emphases are on speaking in tongues, healing or "laying on of hands," spirit possession, and religious dance. There are no inhibitions regarding emotionalism or kinetic style. Musically, the church is very much alive. Singing is accompanied by piano, organ, drums, guitar, tambourine, hand-clapping, and whatever else seems musically appropriate.

In contrast, the small rural Baptist churches tend to adhere to older traditional religious practices dating from the ante-bellum period. For instance, the Square and Neff families make up the core of the Holly Grove Baptist Church, located in Zachary and pastored by Rev. Lorenzo Neff. The church also maintains its own family cemetery.

The small family choir sings traditional hymns and folk spirituals, accompanied two Sundays a month by a hired pianist who is not a member of the church. No other instruments are used. On the Sundays when there is no pianist, the choir and congregation sing a cappella. Contemporary gospel songs are seldom performed, and hymns are frequently lined out by a leader.

Rev. Neff preaches in the traditional Black folk style, and his services are never rigid. For instance, if there is a relative visiting from out of town, the minister may interrupt the service and ask that person to "say a few words to the congregation" or "render the congregation a song," especially if the person has been known to sing a little. Emotionalism is freely expressed at Holly Grove Baptist Church. Holly Grove tends to resist innovation and clings to tradition.

The Black churches in East Baton Rouge Parish mentioned here partially represent a gamut of denominations and a varied observance of folk tradition. These churches are extremely important to the Black community, as well as to folklorists, anthropologists, ethnomusicologists, and any other students of Black culture and tradition. They have been, and still are, great storehouses of liturgical, ideological, rhetorical, musical, and oral narrative traditions.

Religious Musical Traditions

The musical tradition occupies a paramount role in the Black church. Music is a necessary part of Black religion. Indeed, a church service without music is unimaginable. Religious music often enters the lives of church members during childhood. Most Black religious music, especially as sung at this age, is passed on aurally. It is very rare for a Black traditional church not to have a children's or "cherubim" choir, as they are so often called. In the Black community, children's families often teach religious values and practices at a very early age. Black children even play "church" as other children play "house," or "school," or "doctor." Information gathered from several adults who were interviewed and children who were observed strongly suggests that playing church is a common tradition among Black Baptist and Pentecostal children. Preaching, shouting, singing, and playing music are the practices most often dramatized.

After a child outgrows the "cherubim" choir, the natural progression is to the young adult or adult choir. Singing takes place not only in regular church services, but also on other occasions. Many churches have Sunday afternoon or evening concerts or musicals, as well as their annual anniversaries. Church choirs are also invited to other churches to perform, especially when their pastor is the invited guest speaker.

Most religious choirs and gospel groups are affiliated with a specific church, though there are some exceptions. Some choirs consist of members of various churches in the city. One such choir in Baton Rouge is the Voices of Zion, directed by Paul Simon. This community gospel choir consists of dedicated singers and instrumentalists who love to sing gospel music. They come together once a week to rehearse diligently for their next performance, and sometimes just to sing for the "glorification of the Lord." They are a young, struggling, but vital ensemble.

Another group of singers not affiliated with one specific church is the Gospel Quartet. Gospel quartet singing, formally a cappella but now mostly accompanied, has been surpassed in popularity by other styles of gospel music yet retains a small but steady and devoted following. One particular acapella close-harmony quartet in the Baton Rouge area is the Zion Travelers Spiritual Singers, led and managed by Burnell J. Offlee.

The Zion Travelers have been performing in this tradition since the early forties, with one of the original members--the bass singer, Joel Harvey--still performing with the group. The quartet has tenaciously maintained its unique performance style and traditional concepts of quartet harmony. WIBR has presented the Zion Travelers on live broadcast every Sunday morning for over thirty-five years. They perform at various churches, community concerts, the annual River City Blues Festival, and most recently, the Festival of American Folklife in Washington, D.C. The mere fact that this small folk group has maintained its original acapella singing style for over forty years demonstrates its importance in traditional Black culture.

Individuals who do not perform--disc jockeys, booking agents, and promoters--also support the traditional gospel network in Baton Rouge. Disc jockeys play an important role in airing and promoting community gospel groups and programs. On radio station WXOK in Baton Rouge, Eula Mae Hatter, better known in the community as "Cousin Carrey," has broadcast a gospel program since the 1950s. Everyone interested in "being in the know" about religious music and services tunes in to "Cousin Carrey," especially on weekend mornings. She gives a complete rundown on gospel programs and special church activities in the area, along with religious music and special requests for particular tunes.

Another important figure in the urban gospel network is the gospel booking agent and promoter. Outside of the church, gospel music is also heard at special "all-star" concerts presented by promoter/booking agents rather than individual churches.

John Ootsey is a well-known promoter/booking agent in the Baton Rouge area. Unlike some promoter/booking agents who are just businessmen, Ootsey has actually been involved with gospel performance for several decades. He began to sing with gospel quartets (The EF Five and ACapella Harmonizers) in the late thirties in Clinton, Louisiana. Later, he directed gospel choirs, though at the present time he books and promotes only. Ootsey occasionally brings in well-known groups from hundreds, even thousands of miles away. Sometimes this is done to highlight his concerts with local groups, while other occasions are simply "all-star" events. These are usually held at high school auditoriums where admission can be charged. Many Blacks are strongly against charging admission to enter a church--"the house of God." According to Ootsey, Capitol High School is a frequent venue for such concerts.

When asked why he decided to promote instead of continuing to perform, Ootsey responded: "Two reasons. Number one, I can't perform like I did earlier (laugh) or like I would like to, and really I am not getting any younger. Number two, if I keep doing like I was doing I won't get much older (laugh). So for those reasons I decided to promote and help others. This way I can still stay close to the music. You'll be surprised as to how many calls I'll get just for putting out my gospel card."

John Ootsey is more sensitive than most promoters. He possesses the added assets of having grown up in and around Baton Rouge and remaining an active bearer of the gospel tradition of that area.

Bibliography and Archival Resources

Jackson, Joyce M. Card, "The Black American Folk Preacher and the Chanted Sermon: Parallels with a West African

Tradition." in In Discourse in Ethnomusicology II: A Tribute to Alan P. Merriam, Carolyn Card, Gen. Ed. Bloomington: Ethnomusicology Publications Group, 1981.

Ootsey, John. Interview by Joyce M. Jackson. January 11, 1984.

U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Census. Country and City Data Book 1962 & 1983: A Statistical Abstract Supplement. U.S. Government Printing Office.