Table of Contents

Louisiana Folklife: An Introduction

Folklife Research in Louisiana

Ethnicity, Region, Occupation and Family

Living On and Off the Land in Louisiana

Documenting Tradition

Folklife and Public Policy

Appendices

"A Promise From The Sun:" The Folklife Traditions Of Louisiana Indians

By H. F. 'Pete' Gregory

This essay originally appeared in Folklife in Louisiana: A Guide to the State published by the Office of Cultural Development in 1985. This essay is provided online courtesy of the editor since the publication is out of print.

Editor's Introduction

The terms folk or folklife were traditionally not associated with Indian culture. The antiquarian view was that "'primitive" tribal groups around the world were the natural precursors of the peasants in Europe who, along with rural whites and blacks and urban ethnic groups in America, were considered "'the folk." It followed that middle class popular culture and upper class elite culture were respectively further along the continuum. More modern concepts of folk culture use "folk" as a generic term that can be applied to traditional beliefs, practices, and creations of all social groups. Although folklorists and anthropologists are usually reluctant to apply the notions of folklore and folklife to middle class and elite populations--though these groups certainly do have traditions--there has been much less resistance to viewing Native American culture as within the preview of folk traditions. The reasons for this are many, but in a very pragmatic sense it is essential to understand Indian traditions in order to comprehend their influence on rural whites and blacks in Louisiana and elsewhere in terms of folk medicine, foodways, and tales, to mention but a few areas. In an opposite and ironic sense, Indians, due to geographic isolation and social exclusion, have often been the greatest conservators of European and Afro-American folk traditions since the contact period. In Louisiana, for example, one today finds members of the Houma tribe in Terrebonne Parish speaking French more broadly across the generations than most Cajun families. Perhaps even more disorienting to the cultural "Purists" is the fact that Choctaw-Apaches in northwest Louisiana often live in log houses--the classic Anglo pioneer folk house--while the whites have moved into the more prestigious mobile homes and tract subdivisions!

Their connection to other folk groups aside, Louisiana's Indian peoples are important to all of us because they represent the original human adaptation to the diversity of Louisiana environments. As Houma tribal leader Helen Gindrat says, "We were people before we were called 'Indians.'" Despite years of neglect, exploitation, and expropriation of their lands, the Indians of Louisiana have persisted.

Dr. H. F. "Pete" Gregory is a professor of anthropology at Northwestern State University in Natchitoches and is Part Indian. Widely respected as an archaeologist, cultural anthropologist and teacher, he has worked with Indians in Louisiana for over twenty years and is the author of numerous articles on their cultural activities and material creations.

The Indians of Louisiana, in the geographic area longer than anyone else, have maintained their identity. Their presence represents three hundred years of resistance to assimilation for some of them--at least two hundred for all of them. They have managed to survive. Missionaries, government removals, tribal reorganization, schools, and the coming of industrialization have all had their effects. Yet, somehow, the Indian peoples have clung to their own separate cultural heritages. In fact, they have seen their traditions borrowed by non-Indians, even as their own cultures were denied value.

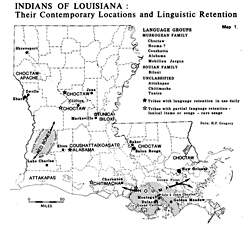

There are slightly more than 12,000 Indians in Louisiana, giving the state the third largest Indian population in the East (1980 United States Census). They are, for the most part, still identifiable as tribal Indians: Houma, Coushatta, Choctaw (at least four different groups), Chitimacha, Tunica- Biloxi, and Lipan Apache-Choctaw (Map 1). There are also a number of nontribal communities of at least part Indian descent. Generally identified as "Redbones" or "Sabines," pejoratives for tri-racial groups (Parenton and Pellegrin, 1950 148-58), these groups are apparently more Indian than anyone (including some of them) will admit. Only a few tribes like the Natchez and their sub-tribes (Swanton, 1911) and the Caddo (Webb and Gregory, 1978) seem to have disappeared from Louisiana. Urban Indians are still in the minority; most Louisiana Indians' communities are far from the "pave." There are, however, Indians in New Orleans, Baton Rouge, Shreveport, and other large cities. Most are part of the traditional Indian communities in the state. However, outside groups such as the Cherokee, Oklahoma, Choctaw. Apache, Ute, Sioux, Chickasaw, Laguna Publoans, Navajo, Kiowa, and others have also relocated in Louisiana. In all cases these Indians have sought out others and have tried, even in urban settings, to maintain their cultural heritage.

Louisiana Indians have lived between the whites and blacks, and both those groups have borrowed freely from Indian culture. All the southeastern Indians have stories which they share with blacks. There are many others that are different in content, and most vary in style and presentation. Stith Thompson in his North American Indian Folk Tales (l929: xxii), noted "African influence" on Southern Indian tales, but he seemed to gloss over the fact that such cultural interchanges were seldom unidirectional.

Linguistically the Coushatta have struggled the hardest and remained the most successful at language maintenance. The whole tribe speaks Coushatta or Koasati as their first language. A few of them speak Mobilian and Choctaw as well. They are extremely proud of their cultural traditions (Johnson, 1976; Rothe, 1963). Recently, with the aid of Eugene Burnham of the Summer Institute of Linguistics, the tribe has produced a series of children's readers in the language (Coushatta Tribe 1979).

The Choctaw at Jena, Louisiana, also have, at least among older people, preserved their dialect of Choctaw. Today one hears the same phrases and words which set them apart from their linguistic kinsmen in Oklahoma and Mississippi that Albert Gatschet heard near Troup Creek in 1886 (Unpublished Gatschet Notes, Anthropological Archives, The Smithsonian, 1886). Recently, the tribal government at Jena instituted a series of classes, funded by the Center for Applied Linguistics. This same group has begun working on a written system for Coushatta, and now, for the first time, children are learning to read their own native language.

In few other states is the Indian language contribution to the culture so obvious. The widespread use of the Choctaw-based Mobilian jargon, a pan-tribal trade language used by Indians, whites and blacks, was important into the late l9th century. Indian place names such as Natchitoches, Opelousas, Attakapas, Calcasieu, Catahoula, and Tensas are ubiquitous and still lend an exotic air to the geography (Reed 1927). The Indian languages have also loaned many words, especially from their Mobilian trade language, to the local dialects of French, English, and Black English as well (Crawford 1975: 1-21; Hass, 1975: 257-65). The last speakers of the Mobilian Jargon were among the Koasati and Choctaw in central Louisiana (Crawford 1977; Dreschel 1978).

Mary Haas (1947:145-58) has described how the Tunica borrowed French words into their native language and William Reed (1927) has discussed the more common reverse of that situation. Not only place names but whole rafts of words in Louisiana French are of Indian derivation. Linguistic borrowing was clearly a two-way street.

The Coushatta Indians manufacture a coiled pinestraw basketry (Lylestine 1973), similar in many ways to that of Sea Island Negro basketry from South and North Carolina (Vlach 1978). However, the forms are different, and the Coushatta use raffia or a soft inner bark for stitching. Apparently the technology--i.e., coiling--produces related forms. The Coushatta have long produced round and oval baskets, many decorated with flowers or pine cones. Open-work "bread trays" have also been made since the 1930s. In the 1960s tribal women elaborated on the basketry and produced a wide array of animals: bear, crabs, crayfish, frogs, etc. One lady even made camels. These baskets have been the center of controversy for a time now. Some experts say the Coushatta learned to make them from home demonstration agents in the 1930s (other rural Louisianians did), but older Indians say they merely substituted raffia and Longleaf pine needles for wire grass and the inner bark of the dogwood (de Caro and Jordan 1980). Wire grass baskets do occur on occasion even now. All these baskets remain the production of the women, and, while a few men broke tradition and tried their hand at the older (?), more traditional, plaited cane basketry, none have made straw basketry. Straw baskets have become part of the tribe's income, but more important, they are also a significant identity factor and a source of pride to the community. In fact, pinestraw has almost completely replaced cane basketry on the reservation in Elton. Several women and at least one man still make the cane baskets, but somehow the craft has lost popularity among the Coushatta.

Further south, in St. Mary Parish, a handful of women have maintained the beautiful split-cane basketry of the Chitimacha tribe. Double-woven baskets, dyed black, red, and yellow, carry intricate, named designs that are thousands of years old (Gregory and Webb 1975). Innovation is frowned upon, and many women carefully curate "pattern baskets" nearly a century old. New baskets are carefully compared to those. The named patterns, such as Alligator Guts, Rattlesnake, Cow's Eyes, Black Bird's Eyes, and Muscadine Rind, are also standardized and provide another conservative element in the art. However, a few innovations have appeared. For example, miniature "needle" cases were made; and in the 1940s aluminum foil was placed between the double walls of cigar cases. These later were mailed overseas to service men. Sometimes an initial appeared on them. Other than these innovations, few changes have occurred. Today commercial dyestuff is often substituted for older plant-derived dyes, and one man has been known to try making baskets. Yet in a community that lost the language in the 1940s, that became basically Christian, and that is composed of families mixed with the French and Anglo neighbors, the maintenance of this complex basket art has become a hallmark of tribal identity.

Recently Ada Thomas, one of the best weavers, has taught younger Chitimacha the basic basket skills at a local day school. Such efforts have been ongoing since the 1940s when the late Pauline Paul ran similar classes for Chitimacha girls (Dorman Collection photographs). A young non-Indian, Tom Colvin, is currently working with Hazel Cousins to preserve the palmetto stem and cane basketry of Bayou La Combe (Colvin 1978). Similarly, Claude Medford, a part-Choctaw craftsman, has preserved as much of the traditional cane basketry technique as possible. Medford also works in other traditional media: gourds, shell, feathers, beadwork, and ceramics. Certainly basketry and some traditional foods will continue among the Chitimacha for many more generations.

The Houma, the largest tribe in the state, are very complicated culturally. They have married non-Indians frequently, but many are of full Indian ancestry to this day. Further, their geographic locations were, until the development of the offshore oil industry, the most isolated in the state. Crafts have survived, and, rarely, octogenarians remember stories and songs of Indian or syncretic French and African origin (Duthu 1980). Many of their mythic themes and motifs are older French themes from their ancestry contact with Acadian and West Indian cultures (Spitzer, 1979). Plaited palmetto mats and baskets suggest Mexican and Filipino origins, but some double-woven ones are clearly Indian forms. Frank Speck notes that, alone of the southeastern Indians, the Houma possessed solid wood blowguns, once a functional artifact, but today used more for sale as a craft or even as tourist art (Spitzer, 1979). Elaborate hardwood blowguns, made of two composite segments and shear-lashed together with twine, are seldom seem; they have been almost wholly replaced by cane or marsh alder ones. The older ones are carefully guarded by the families who have them.

The Houma adapted themselves to the lower coast at an early date (sometime after the 1780s they shifted across the Mississippi from St. James Parish and spread down the bayous). Today many of the men work at oil-related industries, as do their neighbors, the Chitimacha. However, Houma men have also become famous boat wrights and their inland waterway shrimp boats, a type of Lafitte Skiff, are famous among Gulf Coast fishermen from Galveston to Mobile Bay. This folk industry, while tying the Houma to the outside world, has served them well at home, too. They are still among the best fishermen in south Louisiana. Acculturation from l8th century contact has also left them in the position of being among the most traditional speakers of the Acadian dialect in the state. While only snatches of Houma songs and a few isolated Indian words remain, conservative "old-fashioned" French music and language dominate Houma communities. Geographic isolation and the fact that the Houma were segregated from both blacks and whites in schools, movies, churches, and other public places, kept the people together and limited language exchanges. Today, the Houma have selectively integrated the best of both cultures---French and Indian. Change has come, but newer elements, like Lafitte Skiffs, have become powerful recent sources of community identity, and Indian culture has survived.

The Tunica-Biloxi fused in the 1920s; the two tribes had become so inextricably mixed socially and culturally that they chose a unitary chief (Downs 1979: 72-89). Once they occupied several villages, but they now are concentrated near Marksville in Avoyelles Parish. While their last Tunica and Biloxi speakers died in the 1940s, the older people have preserved a relatively large number of both Tunica and Biloxi words. Many remember songs and stories, and at least two men recall the traditional Fete de Ble rituals and the old dances.

Material culture has survived there, too. Older men still manufacture ball sticks or raquettes, and the tanning of deerskins--a Tunica specialty at least since French colonial times--is maintained. Women have their own unique styles of pine needle baskets--the last of their cane basket makers, an Ofo Indian, Alice Picote, died only a few years ago. Horn spoons, once utilitarian items, are now made for craft sales, and occasionally a traditional piece of silverwork is produced. Like the Chitimacha, the Tunica-Biloxi are much mixed with local French families and, like the Houma, they have been severely discriminated against. Their children (even those of predominantly white ancestry), for example, were not able to attend local schools until the 1950s. Coupled with fierce pride and community identity, such social isolation provided the ambiance for the conservation of large blocks of Tunica-Biloxi culture, not to mention that of the Ofo and Avoyel absorbed by them (Haas 1950).

Choctaw, especially near Jena and Georgetown, Louisiana, (Gregory 1977: 2-16), have continued to smoke tan buckskin. Recently Anderson Lewis, their traditional tanner, has taught several younger men to tan. George Allen of Jena, for example, is very active. This core group represents possibly the last active Indian tanners in the whole southeast. Nationally, Indian craftsmen often buy deerskin tanned in the northern plains or by the Mexico Kickapoo.

A single elderly tanner, Paul Thomas, at Clifton, Louisiana, also continues working, but only sporadically. He, like Anderson Lewis, recalls that they tanned the hides to make whip "crackers" and "string" to sell to muleskinners working for nearby logging outfits. Both men learned their skills from their fathers. The creamy brown color and smoky smell of soft buckskin can still be an aesthetic experience in central Louisiana.

In the 1930s and on into the 1950s the family of the late Joseph Pierite, Chief of the Tunica-Biloxi, also tanned their own deerskins. Although they used different techniques than the Choctaw, the method was very traditional. Chief Joe made long hunting shirts, dolls, drums, moccasins, and variety of other things from the materials. His crafts are in collections at the Smithsonian, the University of Pennsylvania, the Denver Museum, and elsewhere.

Stickball was played by most tribal groups in central Louisiana. They played inter-tribally and with each other. These games were popular entertainment for whites and blacks until the 1930s. The Tunica-Biloxi had weekly games on their ballgrounds at Marksville. Older people, both Indian and non-Indian, recall the games with great pleasure. Accompanied by a great deal of gambling and some drinking, the games were frowned upon by the missionaries, and most groups had ceased to play by the 1940s. Those who continued to play did so at isolated spots in the woods so as not to offend ministers. Today older people remember those games vividly and still make, on occasion, the hickory racquets or kapoche, the looped sticks used to handle the ball. Near New Orleans the white Creoles developed their own teams, and blacks also are reported to have played near Mandeville. Like their Indian counterparts these teams had special songs and rituals. In recent years a French team played at Mamou, but the attempt to revive the rough and tumble sport apparently has failed (Dixie Roto 1957). Visits to the Mississippi Choctaw Fair or the spring ball game of the Alabama and Koasati in east Texas help keep the memories alive.

Music and dance were also popular Indian arts. The dances were open to non-Indians as well. At Marksville the tribal elders love to tell of their dance which involved serpentine movements, spiraling into the center and then out again. White Creoles who were present invariably wound up on the end of the line of dancers and were "popped off" into the woods! Most older whites at Marksville, Le Compte, Beaver, and Elton have heard about or participated in the Indian dances. Until the Missionaries became active in the Indian communities (1890-1925), such dancing was very popular. A drum, made of an iron kettle or a cypress knee covered with deerhide, beat with a single stick, was the most common musical accompaniment, but the ex-slave, Northrop, described a dance he attended on Indian Creek in the 1840s, where a fiddle had become part of the music (Northrop 1977). Indian fiddle players have a long history in Louisiana, even though little has been written about them, and their music is virtually unrecorded. In south central Louisiana near Oakdale, the Choctaw family named Blue-eyes was famous for their fiddling at country dances. Similarly, the Toby family in Sabine Parish, also of Choctaw tribal origin, provided a number of fiddlers. Recently, Deo Langley, a Coushatta Indian, has won several contests at Mamou. He seemed to know "older" French songs than anyone else. Alan Lomax has suggested possible Indian cantometric (measurable cultural traits) elements in Acadian music (personal communication 1979), but Indian music remains a virtually unrecognized area of Louisiana folk tradition. Claude Medford, Jr., has recorded Coushatta, Alabama, and Tunica-Biloxi songs and drumming. He also taped a number of fiddle pieces by Joe Langley, a Coushatta. Himself a fine Indian singer, Medford's collection is the best in the state. Ralph Rinzler of the Smithsonian recorded a number of Coushatta songs from the late Arzalie Langley of Elton that are archived at the Center for Louisiana Studies at the University of Southwestern Louisiana, Lafayette. Emanuel Drechsel (personal communication 1979) has taped a fine collection of Tunica-Biloxi songs and fragments.

The Coushatta tribe at Elton has recently organized a youth group which, under the tutelage of Rosabel Sylestine, has attempted to revitalize the traditional songs and dances there. That group eschews the influence of Plains Indian costumes and the pan-tribal "round dances" and "war dances" seen at the urban pow-wows held annually in Baton Rouge, Houston, and at the Alabama-Coushatta reservation near Livingston, Texas. Instead, tribal elders have taught traditional Coushatta songs and dances, especially those of the late Cissie Robinson, the oldest of the Alabama speakers. Thus the Frog Dance, Horse Dance, and others are heard and seen again in Louisiana. Similarly, the Jena Band of Choctaw has held dances featuring traditional Choctaw dancers from Idabel, Oklahoma. They went to Mississippi and brought Prentiss Jackson and his wife to drum and sing in the old Choctaw tradition. Again, the tribal Choctaw at Jena have disdained participation in non-traditional Indian dance activities like pow-wows.

The pow-wow circuit has brought a different approach to Louisiana Indian music and dance (the two are virtually inseparable) in urban areas. The annual inter-tribal pow-wow is held by the Indian Angels, Inc., a pan-tribal Indian organization in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. It is held at various places: Teamster's Union Hall, the Police Youth Camp Grounds, Istrouma High School Gymnasium. Indians and non-Indians alike visit and participate in the dancing, and traditional pow-wow musicians are usually hired in Oklahoma to provide the drumming and singing. Predominantly in a Plains tradition, pow-wow music is heard nationwide, and, like the feather headdress or, "war bonnet," has come to be a strong new symbol of Indian national rather than tribal specific identity, especially to urban Indian groups (Thomas 1970; Booker 1973). Even so, the strengths of traditional southeastern Indian musics have surfaced again at Jena and Elton.

Densmore (1943) collected Chitimacha songs. However, no sacred songs were in that collection. Neither have many of the sacred songs of Coushatta or Tunica-Biloxi made it into collections. Segments of the Elohara or the Midnight Dance, a combination sacred/secular dance among the Tunica, have been taped or at least written down. Most of these have been carefully curated by the tribes as sacred knowledge not shared with outsiders, or they have been lost.

Storytelling, in all its functional aspects, has been kept alive in the Indian communities Swanton 1907: 285-89 and 1817: 474-78). Faye Stouff has preserved recent Chitimacha stories (Stouff and Twitty 1971), augmenting Swanton's (1917: 447-8) and Bushnell's (1917: 301-7) early work. Swanton (1929) also collected Koasati and Alabama stories which are parallel and sometimes identical to those in Louisiana. Byington (1909, 1910) has left us a compliment of Choctaw stories from Bayou La Combe. Mary Haas (1942, 1950) has published a collection of Tunica stories and myths, including snatches of oral history in which she has pointed out the antiquity and strength of those traditions. Bel Abbey, of the Coushatta community at Elton, has recently worked with graduate students at Tulane University and Northwestern State University on Koasati stories (Abbey and Laster 1978). At Jena, Choctaw elders still tell traditional Choctaw etiological stories--possibly the origin of many of the animal tales told by other groups in the Southeast. Such stories are usually told at night and by grandparents. Children learn all sorts of social rules and morals by their example to this day.

Indian joking and humor are as well developed in Louisiana as they are elsewhere in North America. Frequently they involve the white man, but outsiders seldom hear them and those who do complain that Indians joke "too hard." For example, "ugly anthropology" stories abound in Indian home settings.

An example is one told by a Coushatta. "The anthropologists came over. They asked questions all about us. How did we cook? How did we eat? Finally one asked me, 'How do you sleep?' I said, 'Pretty well, until you began to ask all these silly questions!'"

The geographic and social isolation of Indians from other groups is clearly a by-product of their past contact and conflict with whites and blacks It has, in a real way, contributed to their continued strong identity, and even those who leave the kin-based communities still never abandon them entirely. Home visits are frequent and kinship ties very strong. Some Indians have had their deceased members returned from Texas for burial on tribal land.

Stereotypes suffer, however, upon meeting Louisiana Indians. Few relate to the "uniform" of Indian identity seen elsewhere in the nation."War bonnets" appear at pow-wows but are not part of Louisiana Indian traditions. Instead, long men's "hunting shirts," sometimes edged with rick-rack, are traditional dance costumes among the Coushatta; ribbon appliqué shirts and long buckskin hunting shirts were traditional Tunica clothing. The Tunica frequently chose bright colors; red, white and blue, were their favorites. Coushatta kept yellow, black, red and white preferences, the older sacred colors of the southeast. Tunica silverwork had virtually ceased by the 1880s, but many families still keep an array of ornaments of hammered and polished coins and German silver. One Tunica burial even contained the tools of the silversmith's trade (Gregory 1979). Broaches, arm bands, head bands, bracelets, ear and nose ornaments, breast plates, and other items were popular in traditional dress. After 1760, such items spread widely among the state tribes (Gregory 1965). Ribbons, introduced originally into the Indian trade when surplus patriotic ribbons flooded the country at the end of the French Revolution, have continued to be traditional decoration, especially in women's clothing (Underhill 1949). Beadwork, both the traditional scroll baldrics and complicated chain-meander pattern loom beading, as well as necklaces--Venetian collars and "Daisy Chains"--continue among the Coushatta, the Choctaw at Jena, and the Tunica-Biloxi.

Worn singlely, any of the above items are not a necessary mark of "Indianess," but in combination these elements are clearly so. Younger Indians are increasingly drawn to pan-tribal symbols, too. American Indian Movement (AIM) buttons surface in urban areas, and bumper stickers appear such as "Official Indian Car," "It's hard to be humble and Indian," or "Custer died for your sins." Black felt hats with beaded bands, turquoise and silver jewelry, heishi necklaces---all in a southwestern or Plains tradition--are beginning to appear, but are still integrated with the older southeastern forms. These items contrast with the western boots, jeans, denim work shirts, and overalls of the often more traditionally tribal rural folks. Palmetto hats, made at home by the Houma, are still more popular than imported Indian elements down on the bayou.

Toy pirogues, blowguns, moss dolls, basketry, horn spoons, Chinaberry necklaces, seed necklaces of Mamou "beans," wooden crabs, crayfish, and birds offer striking contrasts to the stereotypes of Indian crafts.

Folk medicines in Louisiana are more often Indian than European or African. Frank Speck (1943) has pointed this out graphically for the Houma, and Spitzer (1979) has suggested that medicinal plants and traditional cures are a strong Indian identity factor for those people.

Many strange foodstuffs that fall upon one's palate in Louisiana came from Indian dietary schedules (Speck and Dexter 1946: 35) Alligator tail, garfish boule and steaks, Gros Bec or Night Heron (an illegal delicacy), filé, turtle eggs, baked raccoon or opossum, deer liver, and a number of wild plants and fungi are seldom known to people from outside the region. Corn dishes abound, as well. Though they are frequently highly seasoned today, they are still clearly Indian in origin. The Coushatta continue to serve their traditional corn soup, chawaka, a version of sofki, once a widespread Indian food in the southeast. On the Sabine River, in northwestern Louisiana, the descendants of Choctaw and ex-slave Apacheans have preserved the tortilla, tamale, and beans traditions of more typical southwestern Indians. Mixed with other Spanish colonial influences, these foods have long served to set the area's identity apart. Fried bread, both wheat and maize, are typical Indian foods all over North America. The Louisiana Indians continue that tradition, too. Choctaw and Tunica make "blue corn" dumplings, eaten with mustard greens, and talk about tomfula, their favored pounded corn food. While some Indian foods, like crawfish, have become Louisiana culinary delights, it should be pointed out that many Houma still refuse to eat them. The Red Crawfish, Shakei Homa, was their "war animal," a guardian spirit. Tunica-Biloxi refuse to eat the dove and Coushatta decline to eat the totems of their clans. Even so, the Louisiana diet is resoundingly Indian-based especially in terms of fished and foraged items.

All the traditional Indian cultural elements noted here have come together in Louisiana with various Anglo-, Afro-, French, or Spanish influences, but Indian communities have held to their own identities. Most native Louisianians (other than the Indian people) are oblivious to the rich Indian heritage around them and remain unaware of such cultural borrowing, even though they daily participate in selected aspects of it.

Efforts by the tribes to obtain services and to develop their own limited lands and resources have frequently been hampered by the lack of education of the general public and state officials about the Indians who have survived in Louisiana. It is easy to ignore things that have disappeared, to forget where things came from, and not to know. However, today the combined efforts of the tribes have begun to have their results and their Indian identity is increasingly preserved and important. As one Choctaw leader, Clyde Jackson, has put it: "We take care of ourselves. We draw strength from our culture." The wisdom of the late Tunica chief, Joseph Pierite, adds optimism to the efforts of such younger leaders: "We have a promise from the sun. As long as there is the sun, there will be Indian people here."

Bibliography

Booker, Dennis A. "Indian Identity in Louisiana Two Contrasting Approaches To Ethnic Identity." Master's thesis, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, 1973.

Burnham, Gane, ed. Naas Mathaali and Naas Onapa: Animal Book. Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana, Elton, 1979.

Bushnell, David. "The Choctaw of Bayou LaCombe, St. Tammany Parish, Louisiana." Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 48. Washington, 1909.

Colvin, Thomas A. Cane and Palmetto Basketry of the Choctaws of St. Tammany Parish, La Combe, Louisiana. Melba Elfer Colvin, ed. and publisher, Mandeville, 1978.

Crawford, James M. "Southeastern Indian Languages." In Studies in Southeastern Indian Language. James M. Crawford, ed. University of Georgia Press, Athens, 1975.

____. The Mobilian Trade Language. University of Georgia Press, Athens, 1977.

de Caro, Frank and R. A. Jordan. Louisiana Traditional Crafts. Louisiana State University Union, Baton Rouge, 1980.

Densmore, Frances. "A Search for Songs Among the Chitimacha lndians of Louisiana." Anthropological Papers No. 19, Bureau of American Ethnology, Washington (1943): 1-5.

Downs, Ernest C. "The Struggle of the Louisiana Tunica Indians for Recognition." In The Southeastern Indians Since the Removal Era, Walter Williams, ed. University of Georgia Press, Athans, 1979.

Drechsel, Emanuel. "The Mobilian Jargon." Doctoral dissertation, University of Wisconsin, Madison, 1978.

Gatschct, Albert. "The Chitimacha Indians of St. Mary's Parish, Southern Louisiana" Transactions of the Anthropological Society of Washington. 2(1883): 148-158.

Gregory, R. F. "Indian Silverwork." Louisiana Studies. 3(1965).

____. "Jena Band of Louisiana Choctaw." American Indian Journal. 3(1977): 2-16.

Haas, Mary R. "The Solar Deity of the Tunica", Papers of the Michigan Academy of Science, Arts and Letters. 28(1942): 531-35.

____. "Men and Women's Speech in Koasati." Language. 20(1944): 142-49.

____. "French Loan Words in Tunica." Romance Philology. 1(1946): 145-48.

____. "Tunica Texts." University of California Publications in Linguistics. 6 (1950): 1-174.

____. "What is Mobilian?" In Studies in Southeastern Indian Languages. James M. Crawford, ed. University of Georgia Press, Athens, 1975.

Hoover, Herbert T. "The Chitmacha People." Indian Tribal Series. Phoenix, 1976.

Hunter, Donald G. "The Settlement Pattern and Topanymy of the Koasati Indians of Bayou Blue." The Florida Anthropologist. 26(2)(1973): 75-88.

Johnson, Bobby H. "The Coushatta People." Indian Tribal Series. Phoenix, 1976.

Kniffen, Fred B. The Louisiana Indians. Bureau of Educational Materials, Statistics, and Research, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, 1945.

Northrup, Solomon. Twelve Years a Slave. Sue Eakin and Joseph Logsdon, eds. Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge, 1977.

Parenton, Vernon J. and R. J. Pellegrin. "The Sabines: A Study of Racial Hybrids in a Louisiana Coastal Parish." Social Forces. 30(1950): 148-154.

Peterson, John H. "Louisiana Choctaw Life at the End of the Nineteanth Century." In Four Centuries of Southern Indians. Charles M. Hudson, ed. University of Georgia Press, Athens, 1975.

Reed, William A. "Louisiana Place-Names of Indian Origin." Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Bulletin No. 19. Baton Rouge, 1927.

Rothe, Aline. Kalita's People: A History of the Alabama-Coushatta Indians of Texas. Texan Press, Waco, 1963.

Skeeter, Andrew. Summary Analysis of Clifton Choctaw Community. Andrew Skeeter Associates, Oklahoma City, 1978.

Speck, Frank G. "A List of Plant Curatives Obtained from the Houma Indians of Louisiana." Primitive Man. 4(1941): 49-73.

____. "The Houma Indians in 1940." American Indian Journal. 2(1)(1975): 4-15.

Speck, Frank G. and Ralph W. Dexter. "Moluscan Food Items of the Houma Indians." Nautilus, 60(1)(1946): 34.

Spitzer, Nicholas R. "The Houma Indians." In Mississippi Delta Ethnographic Overview. Nicholas R. Spitzer, ed. National Park Service, New Orleans, 1979.

Stouff, Faye and W. Bradley Twitty. Sacred Chitimacha Beliefs. Twitty and Twitty Inc., Pompano Beach, 1971.

Swanton, John R. "Indian Tribes of the Lower Mississippi Valley and Adjacent Coast of the Gulf of Mexico." Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin No. 43. Washington, 1911.

____. "Early History of the Creek and Their Neighbors." Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin No. 73. Washington, 1922.

____. "Myths and Tales of the Southeastern Indians." Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin No. 103. Washington, 1929.

____. "Source Material on the History and Ethnology of the Caddo Indians." Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin No. 132. Washington, 1942.

____. "The Indians of the Southeastern United States". Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin No. 137. Washington, 1946.