Secular Music

Somebody give a dance and they would take down the beds in the front room and sprinkle meal on the floor for easy moving. -- Hugh McGee

In my family there was a lot of fiddle-players. My daddy played a little bit, my grandpa's on both sides of the family played a little bit. I had a great uncle and cousins that all played a little bit. But I heard fiddling all my life but I started out playing a guitar when I was about seven years old; I sawed around on it. I never did try to play a fiddle till I was about thirteen. -- Fred Beavers

How I got started, I was sittin' around and I heard a girl -- she had a little music talent -- she played a little old song about "Hattie" and I learned it. From then on I went on playing...I ain't never taken a lick of music lessons. I used to play for white people when I was working for wages by the month on the farm. -- Mitchell Shelton

The play parties or house dances popular in the early days in north central Louisiana usually had music provided by a fiddle and a guitar. Somewhat later mandolins and basses were added to make a four-piece string band. Every community seemed to have a small group of musicians. These bands often consisted of several family members. For example, the Beckham family band included Roy Beckham on fiddle, his sisters and one brother on guitar, and a brother on piano. The waltzes, breakdowns, and reels hailed from the British Isles. Both square dancing and round dancing was common at these events although many Baptists frowned on it. According to reminiscences of Eva Colvin and Lula Revels, one could be thrown out of the church for dancing. Nevertheless, this did not stop even the preacher's children from participating.

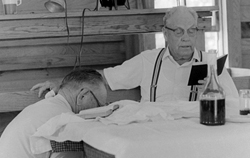

Eta Crowell, who played bass violin with the family band, also learned a number of ballads and parlor songs from her father. Today this ballad tradition has all but disappeared from the north central area; however, the breakdowns and waltzes are still performed by old-time country musicians such as Bill Kirkpatrick, Fred Beavers, fiddlers; Lesley Raborn, mandolin; and guitarists Tracy Tyler, Verley Carr, and Gene Harper. Today these musicians no longer play for house dances. Instead they "jam" together at each other's homes in much of the same fashion as the earlier "shade tree" and "front porch pickers" used to do. Some musicians such as Fred Beavers join country western bands to play for dances such as the "over 50 dance," held monthly for senior citizens.

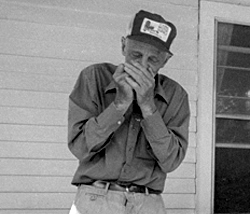

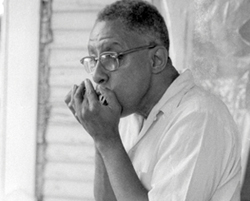

Although it is rarely used in string band, the harp or (harmonica) is still a popular instrument for playing traditional country and gospel tunes. Often the harp is played alone (see Figure 14) for self or family entertainment. Other musicians including Lawrence Rippertoe who plays both harp and fiddle like to have a guitar to play "second" (Figure 15).

The old-time musicians still playing today have been heavily influenced by blues, minstrelsy, jazz, popular music, and by radio, especially the Grand Old Opry, which began in 1925. Out of this music came western swing, contemporary country-western, and bluegrass, which are still highly popular in the area today. Bluegrass festivals held during the warm months throughout north central Louisiana, draw hundreds of fans, and many new musicians who learn to play primarily in the folk tradition from other musicians. The music is both learned from other musicians in the festival or jam context and from records. The bluegrass festival is noted for its wholesome atmosphere in which no drinking or drugs are permitted.

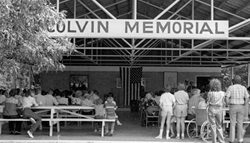

Also popular in the area are the "country music shows" such as Ruston's Wildwood Expres, Homer's North Louisiana Hayride, and Shongaloo's Red Rock Jamboree which are modeled after the Louisiana Hayride in Shreveport (Figure 17). These shows feature mainly country-western music with a touch of gospel and rock & roll. Dancing is a rarity although the Homer Hayride is followed by a dance.

Although blacks in the past participated in the Anglo-country music tradition, they popularized another traditional music form -- blues. Some musicians such as Charles Ellis Dawkins, harp player, play both blues and country music (see Figure 16). Today few country bluesmen remain in the area.

One form, which seems to have disappeared, is fife music. David Allen remembers how to make the flute-like instrument which he calls "quill;" however, the last quill-blues player he remembers, "T-bone" Smith, died several years ago. Many who formerly played blues have switched entirely to gospel music, feeling that blues was a negative type of music. Eighty-year old Mitchell Shelton disagrees with the idea however: "I don't think it's any harm in playing them [the blues]. God likes music himself. My suggestion is this -- God likes all music; it's just what you use it for." Today Mr. Shelton plays blues guitar and sings mainly for himself at home, although he sometimes joins some local white youths who are learning to play blues from him and also sings gospel with his wife. The younger blacks throughout the area have turned primarily to popular music, although a few rhythm & blues groups can be found. Many of the younger groups such as the Sensational Golden Wonders show much rhythm & blues influence in their instrumental and vocal styles.

Country music, along with blues, was moved into the bars or "honky-tonks" in the twentieth century when rural people began to move into the cities for work in industry. This changed the image of both forms of music, causing the music to be regarded with some ambivalence by its original adherents. Nevertheless, today's audiences for both types of music with their more recent developments prove them to be some of the most popular entertainment in the region.

Religion And Family

And the next day, he carried me over to a pool, a pond and baptized me. He said, "Well, this is the first one I've baptized, and I've baptized a hardshell preacher." He walked out to the water's edge, and he said, "Here's y'all's gift to the church. We'll start using him." I was just a gift to the church as a minister. -- Hilton Mercer

The religious practices of the Scotch-Irish who settled in North Louisiana were according to the specific Protestant denomination. Generally, Protestants in the area have been evangelical fundamentalists of mainly Baptist and Methodist persuasion and a few Presbyterians. Many slave holders held religious services for their slaves who adopted their masters' religions with some modifications. Consequently, the majority of blacks in the area today are also Baptists and Methodists; however, their churches remain for the most part, separate from whites, although their traditions are similar. Early church meetings for the pioneers and the slaves before the war were often held in brush arbors and directed by an itinerant minister with little regard for denominational differences. However, North Louisiana communities were quick to build churches as soon as the population could support them. Even after churches were built, periodical revival and camp, or tent, meetings would be held in various regions, drawing crowds of all denominations from several surrounding communities. Often these ministers conducting these meetings and pastoring the churches were traditional folk preachers with a "call to preach" but with little formal education (Rosenberg 1970).

Still today many fundamentalist ministers receive this "call." Some go on to seminaries after the call as did Rev. George Hood, pastor of Zion Hill Baptist Church in Grambling. Yet many such as Hilton Mercer and David Godwin, of the Primitive Baptist belief, began preaching soon after their call, their only training being Bible study within the church.

Many of these folk preachers may have learned their techniques of preaching within the church they attended, but they believe that their inspired sermons are given to them by God, through the Holy Spirit: "We are just an instrument. The Holy Ghost is the comforter" (Hilton Mercer). A congregation can also tell if the preacher has been divinely inspired according to the way in which the sermon is delivered. "If you was gifted and really preached a sermon, then they ordained you; but if you got up there and talked and the spirit didn't hit you just right, they could tell" (Hilton Mercer). Generally, if the preacher develops a rhythmic, almost musical chant, he has the Spirit. According to Rev. George Hood, when he receives the Spirit, something outside himself takes over, and he may not even remember what he has said later.

In spite of differences in preaching styles, belief, and doctrine among the different Protestant denominations, in general their services have much in common, reflecting their common backgrounds.

Many community churches still maintain a complex of religion-related traditions which were common in frontier and plantation days. Sunday afternoon singing with "dinner on the grounds" can still be found. In fact, gospel singing, an important aspect of Protestant worship service, may be even more popular today with the expanding country-western music market. Often gospel singing ensembles are composed of family members who visit different area churches to "witness for Christ" through their music. Gospel techniques and four-part harmonies are usually learned at a young age through the oral tradition and hymnals (often still using the shaped-note system). At the turn of the century, many churches sponsored singing schools held by traveling music teachers who taught gospel music with the seven-note shaped system.

Learning to sing in the church, Alvia Houck, of Hico, attended such a school in his youth in Hico. Today his eight children take turns singing with him in a gospel quartet. In regard to their abilities, Mr. Houck comments, 'The only thing I can say about it is that itwas a gift from the Lord. He blessed with it...and he blessed me by my children having the talent to sing." Although the Houcks also sing some country music, their favorite is gospel music. There are a number of such family gospel groups in the area such as the Balls, from Ruston; the Fullers, from Eros, and the McCartys from Quitman. These groups perform at churches, gospel festivals, country music and bluegrass shows, and area benefits (see Figures 20, 21, and 22).

Black gospel music includes much of the same music as white gospel since many of the songs were learned during slavery and were sung in the fields along with work chants. Often rhythms are different, and the African tradition of call-and-response will be used in the singing. This is most obvious in the singing of the "old Dr. Watts hymns," usually done after the devotional reading by deacons of the congregation. One of the older deacons may sing or chant a line of a hymn and the congregation will repeat it after him, line by line. These hymns which are usually quite slow are different from newer more upbeat songs usually accompanied by piano or organ, which feature soloist and choral selections. Music holds an important place within the black churches in the region as evidenced by the number of gospel fests, and other special song services. One reason for its importance may be that it, like a sermon, can evoke an ecstatic religious experience, an important feature in the Black church, which, no doubt, reflects an African influence.

Black and white churches in many areas are also an important part of a complex of burial traditions. Older community cemeteries are frequently located at churches and are the focus of annual Memorial Day and Homecoming services. For this event, church and community members and families who have moved away gather to commemorate their dead with a religious service and an outdoor dinner, often followed by a "graveyard working," in which the gravestones are cleaned, grass trimmed, and flowers placed on graves. In earlier days before power mowers, graveyards, like yards, were kept free of grass by scraping with a hoe. Today, only a few are still scraped, although many older people today still prefer scraped graves because they "look nicer." In some mowed cemeteries, some graves are still kept clean according to a family member's wish. One such person left strict instructions that not one blade of grass be allowed on his grave. Consequently, his plot is the only bare spot in the cemetery (see Figure 23).

Black cemeteries, like their churches, have remained segregated, and their graves are often decorated with bits of glass, broken clocks, and other symbolic objects in addition to traditional headstone markers. This practice may be based in African tradition (Vlach 1978: 139), as are many other practices in black religion from the emphasis on ecstatic religious practices to the institution of the burial society.

Unlike the burial above ground in South Louisiana, graves in North Louisiana are below ground. Gravestones have changed from the crude red ironstone rock markers of the poor pioneers and slaves to the upright granite and marble headstones of later settlers and contemporary rural residents, although the modern Forest Lawn-type cemetery is becoming a burial choice of many today. Family plots in old church cemeteries were sometimes set apart with a wrought iron fence. Many early settlers, especially before there were nearby churches, established family cemeteries on their own land. Although some of these have been neglected and taken over by new forests, many of them are still conscientiously cared for by family members who make periodic visits, usually on Sunday afternoons (see Figure 24). This tradition of keeping the family together even in death remains strong. Even in modern cemeteries, family members are still reserving several adjacent plots to insure that they will be buried with their families.

This importance of family is also apparent in other religious traditions, especially rituals such as funerals and weddings as well as holidays. Even though funeral rituals are now directed by funeral homes, funerals continue to be strongly religious occasions attended by the extended family of the deceased. In more rural areas, wakes are still occasionally held at the home or church of the deceased; however, this practice usually now takes place at the funeral home. Rural community members continue the tradition of bringing food on the days before the funeral for the bereaved family, so that the extended family can gather for meals before and/or after the funeral.

Extended family meals are also common on religious and secular holidays such as Christmas, Easter, Thanksgiving, or New Years, and especially at family reunions (see Figure 25). Often Sundays are also a time for family visiting. During these visits, infants and young children are often the focus of attention, perhaps reflecting the culture's feelings on family perpetuation. This traditional emphasis on family and religion makes up an important part of the culture of North Louisiana and has, no doubt, functioned to maintain the rather conservative atmosphere in the area.

This conservative nature of the region has, in turn contributed to the maintenance of many folkways today. While many poorer people have been forced by economic necessity to retain many of these traditions, some have chosen to cling to their folk traditions for other reasons. Some choose a more traditional lifestyle out of a sense of loyalty to their families or the past. Still others actually have an aesthetic preference for the older familiar forms which may seem more attractive than newer ways. Often these traditional forms and performances are thought to be more lasting and worthwhile. In many cases, folk traditions appeal to the basic thrifty nature of those who follow the "waste not" philosophy because many folk practices and forms rely on recycled materials. The questions as to why some folk forms and practices are in danger of disappearing while others have grown and been adopted in popular circles and which forms will be able to withstand pressures of mass culture can only be answered by future research and the passage of time. If the tradition bearers have it their way, these traditions will all be maintained. Indeed, some tradition bearers have passed their skills along to their children; yet others are saddened at the fact that none of their family has shown any interest in learning them. They feel that their heritage is a valuable gift from the past which they wish to pass along to the future. It will be up to the present generation to decide if it wishes to accept this trust.