Introduction to Delta Pieces: Northeast Louisiana Folklife

Map: Cultural Micro-Regions of the Delta, Northeast Louisiana

The Louisiana Delta: Land of Rivers

Ethnic Groups

Working in the Delta

Homemaking in the Delta

Worshiping in the Delta

Making Music in the Delta

Playing in the Delta

Telling Stories in the Delta

Delta Archival Materials

Bibliography

The Delta is an Indian Place

By Hiram Ford "Pete" Gregory, III

Editor's Note: In the early 1990s, Pete Gregory wrote these personal reflections about Northeast Louisiana's Delta and they are published with minimal editing. Also see his Musings on the Louisiana Delta from a Native Son.

The Delta is an Indian Place

The Delta is an Indian place. Hundreds of prehistoric sites are scattered across the Delta landscape. Burial mounds, temple mounds, some among the largest earthworks in North America, have stood as a constant reminder to the people of the Delta of Native American occupations of the land.

Mounds and Artifacts in the Delta

The mounds in particular remain and were appreciated by those who came later and adapted them for other uses. The place names remain today, even after the livestock and people were no longer there—Irish Pen Mounds, the Wild Hog Mound, the Jim Kay Pen Mounds, and Enack Wiley Pen Mound. At the edge of the Cocodrie Swamp is Dixie Mound, the site of an old hog and deer hunting camp. Jonesville still has Mound Street, which winds between two large mounds and reminds people of the great mound destroyed there. In fact, one can hardly go into any of the Delta parishes without seeing or hearing about mounds. For thousands of years they have been a human response to and artistic manipulation of the alluvial wetland. They are all over the place! One mound on Black River in Concordia Parish, Flowery Mound, was enough of a landmark to become a steamboat landing place. The area is still called Flowery Mound Landing. Sally Warren Mound near Lismore, Louisiana, has a very extensive white cemetery on it. Stock Landing Mound in Rapides Parish was widely known until it was excavated in the 1930s. There is a town named Mound in Madison Parish, a place only a short distance from the little town of Delta. The list could be expanded.

Indian artifacts were, and still are, plentiful in the Delta region. Almost every family had a small collection of "Indian rocks." Until gravel roads appeared, these were the only stones to be found in the alluvial valley. Everything found there was of Indian origin. Arrowheads, called "thunderbolts" by African Americans, and sometimes "spears" by older Anglo-Americans, were all over the sites. Collecting artifacts is still one of the prime avocations of Delta people. Some have huge collections. The late Carl Alexander of Epps left collections of thousands of artifacts from the Poverty Point site in West Carroll Parish. He collected the site fields daily for over a quarter century. In Ouachita Parish, a group of collectors became semi-professional pot-hunters, making probes of long steel rods and "poking" to find skeletons and the clay pots buried with them. Vessels found were kept in collections or sold on the antiquities market.

Old nutting stones, pitted to hold hickory nuts, were collected and used for their original purpose. The large mortars or grinding basins became "gate weights," net weights or "loads," and the largest were water or food containers for chickens. Plummets, a football-shaped bola weight often made of imported exotic stones like hematite or magnetite, were collected to use as "chunking rocks." One old-timer from Franklin Parish recalled tying a cloth "tail" on his plummet so he could recover it easily. Squirrels, birds, and rabbits were hunted that way. The intrepid archaeologist Clarence B. Moore, prowling the Delta in his steamboat the Gopher, collected one of these weights near Poverty Point. It was white chalcedony, and the elderly black man who owned it dyed it annually and used it to "peck" eggs at Easter.

In Catahoula Parish, Mrs. U. B. Evans and Kenchen Floyd searched down a legendary "Limber Man." Supposedly made of stone, the artifact had movable arms and legs. Mrs. Evans had the only part the finders had kept: a beautifully polished and drilled leg-shaped object.

The Indians themselves were the source of other folklore, too. There was the skeleton of the Indian found at Larto Lake who had a four-foot-long femur. Then there were mandibles that fit around a grown contemporary man's mandible. The myth of the "race of giants" thought to have constructed mounds in North America did not get into the Delta, where folks knew they were built by Indians. Not everyone knew why Indians had built them and most people thought they contained graves or were used as bases for signal fires.

There were the ghosts, too. Oliver Wiley and the late Louis Wiley of Larto could tell about gates that rattled when there was no wind—the post had penetrated a burial, and when the bone was reburied the rattling stopped. There also was the "person" that could be seen on the mound by their house on moonlit nights until they recovered a burial that had washed out behind their porch. Of Indian descent themselves, the Wileys, a Larto Lake family, held and continue to hold the old Choctaw belief that the soul stays with the bones.

Contemporary Tribes of the Delta

Contemporary Indians—especially the Tunica, Biloxi, and Choctaw who held the Delta in the late 18th into the 19th century, now live in areas marginal to it. The Choctaw, once widely met with in the region, are now found only in LaSalle Parish, "up in the hills" in Delta parlance. They once had villages on Bushley Bayou in Catahoula Parish and on Catahoula Prairie near Enterprise. When the Swiss linguist Albert Gatschet visited them in the 1880s, he noted that some of them had lived on Turkey Creek in Franklin Parish. The early 19th century explorers, Dunbar and Hunter, met Choctaw near present-day Hebert on the Ouachita, and the French traveler Robin noted numbers of Choctaw hunters and their families at Ft. Miro (present-day Monroe). Choctaw hunters and their families prowled the Ouachita in the Spanish Period (1763-1800) and left villages west of Monroe. Socially isolated from both whites and blacks until almost the present generation, the Jena Band remains one of the strongest enclaves of Indian culture in the state.

The Jena Band of Choctaw, with reinforcements from Mississippi after the Civil War, has kept its language. The tribe has also maintained religious beliefs. Some families only became Christians in the 1940s and there is still a strong belief in "medicine." Plant and other cures are still in use. Her father, the traditionalist Anderson Lewis, refused to use white man's medicine unless it was taken by mouth. Needles were taboo.

Mary Jones of Trout pointed out that medicine men had their own territories and that should they encounter one another, a terrible supernatural storm would ensue and one would kill the other. She noted that these people have a dualism and power that can either be for good or evil.

Stories of the little people who hatch from stone "eggs" (geodes or concretions found in gravel beds) are common. Usually, these are "little green men" and they attach themselves to special people as helpers. One elderly Choctaw man always set a place at his table for these little beings. Anderson Lewis told the Shokut anompa (Hog Stories) to his grandchildren. These are explanatory tales with morals attached, much in the vein of Aesop's fables. There is the story of "Why Possum Grins," "How Bear Lost His Tail," "Why Turtle is Ugly," and others. Anthropologist-journalist, William Day, worked with Mr. Lewis on Choctaw ethno-astronomy and collected a number of star myths.

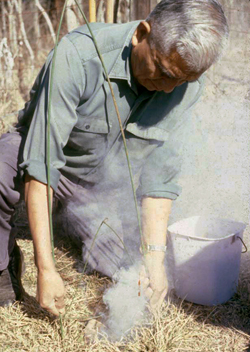

The Choctaw also continue their traditional crafts. Anderson Lewis passed on the skill of tanning deer hides to Clyde Jackson and now Clyde is the elder who's passing it on. The Jena Band tanners are the last to practice the art in the state. Smoke and egg tanned deerskins survived to become boot strings or whip crackers for the early loggers. Tribal people cherish the hides, soft as chamois, and keep them around their houses as "throws."

The Jena Choctaw had a community on the Bushley, a large bayou that drains an area between Catahoula Lake and the Ouachita River. Bashli in their language means a "cut," in this case a short cut. Bushley is but one of a multitude of Choctaw place names scattered about the Delta. Some mark the presence of the Choctaw in the past, while others seem to have been brought by planters from the Mississippi Delta counties. Still, the Delta parishes are spotted with Muskoghean words. Some, like Panola or Penola (Choctaw for cotton), are plantation names. Okelusa (Choctaw for black water) is a post office in Ouachita Parish; Bayou Louis in Catahoula Parish is derived from the Choctaw word, lusa for black or dark. Catahoula, a controversial word attributed to the Choctaw word for "white water" or "beloved water," may actually be a Tunica word derived from Hokatalu, the word for breadstuff.

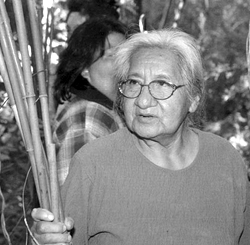

Rose Fisher carries on the cane basketry tradition of her great, great aunt Mae Lewis. Christy Lewis-Murphy makes chinabrerry necklaces, an artistic tradition she learned from Mary Jones.1

The Tunica-Biloxi, a composite of two remnant tribes, now reside on the Avoyelles Prairie across Red River, south of the Delta. Individual Tunica-Biloxi hunted the Black River swamps and commercially fished there until the 1940s. In the 19th century, their major hunting grounds and salt springs were in that area. Toponymy with such Tunica words is rare, but there is at least Colewa Creek near Delhi. "Colewa" means a "drip" in Tunica.

Ouachita has been attributed to the Caddoan language and was a tribal name. A Choctaw folk etymology would compare it to their language's Owa chitto, "big hunt." This is especially interesting inasmuch as the earliest Choctaw showed up in the region as migratory bands of hunters from Mississippi. Most archaeologists now agree that prior to the 18th century the Ouachita River area was populated by Koroa, a group speaking a language related to Tunica. The Ouachita tribal presence was a later, short term occupation.

The Natchez and Tensas, two related tribes in the southeastern corner of the Delta parishes, disappeared from the area but left place names: Tensas (as in the parish and stream names), Little Tensas (a stream in Tensas Parish), the Tensas Trading Post (the name of a store in Concordia Parish in Clayton, Louisiana), and of course, Natchez, Mississippi. Other than place names, the most lasting impact on the region by the Natchez is the widely told tale that the Natchez buried a golden treasure in the Delta. There are several variations, but the story has been collected in Concordia, Catahoula, Tensas and Rapides Parish (Gregory field notes 1960-1980). Usually, the treasure was buried in a prehistoric mound, and it invariably was gold stolen by the Natchez when they destroyed the 18th-century French settlement of Fort Rosalie (modern Natchez, Mississippi). One version has it as a "golden Christ," another has it as a "golden coach," but all agree it was gold. The numerous holes seen in the mounds left by generations of treasure hunters can but attest to the strength of the tradition.2

Near Sicily Island, Louisiana, there are other stories about the Natchez who fled French retribution and took refuge in the Delta. People there point out that a Natchez fort was on Ditto Plantation. In spite of the fact that archaeologists have empirical evidence it was elsewhere, local folks still tell you it was Ditto Lake. The Peck family has another persistent tradition (Jon L. Gibson, personal communication 1984) that the last surviving Natchez, an old woman, died on their plantation near Sicily Island. In the 1930s, many of the French and Indian families near Catahoula Lake maintained that at least some of their ancestry was Natchez. Mrs. U.B. Evans maintained that their fierce anti-Catholicism and lack of French tradition may be attributed to their Natchezan roots. Many such folk beliefs persisted into the 1970s, but are beginning to disappear. Still, the Natchez war in the 1730s remains a lively source of regional Indian-related folklore.

The Tunica, now inter-married with the Biloxi, Ofo, and Avoyel, are actually credited with the extirpation of most of the Natchez. Their traditions are filled with stories of their wars with the Natchez and their prowess as warriors for the French and later for the Spanish. Tunica-Biloxi told such stories to linguist Mary Haas in the 1930s and continue to tell versions of them today. Their militancy is still a point of tribal pride, and local traditions frequently bear on that. For example, Fred B. Kniffen (personal communication, 1987) recalled that Chief Sesostrie Yuchigant told him in the 1930s that the Coulee des Grues, a large stream along the tribal land boundaries, was washed out by the vomit of buzzards that had engorged themselves on the blood of tribal enemies, Avoyelles Indians in his version, killed by the Tunica.

Delta Tribes' Folk Traditions

Tunica stories were published in Mary Haas' Tunica texts and a number of her other works. However, contemporary Tunica storytellers are still at work. Merlin Pierite told another version of the origin of Coulee des Grues which was collected in the summer of 1988. "There was a great animal. I don't know what it was. Just big, you know, like a cow. Them animals traveled back and forth between the two swamps, back and forth. They wore down a path and it became the Coulee." Merlin told how his father followed some kind of big animal one night, trying to rope it from his horse, but it disappeared into a deep place (trou in French) in the coulee. He implied it was one of the mythical "great gray animals." Sometimes the local people confuse the French words, Grues (meaning a crane) with Gris or "grey." That is generally attributed to the great animals which were grey.

Another Tunica-Biloxi and the daughter of traditional Chief Joseph Pierite, Sr., Ana Mae Juneau pointed out the "cave" where the mythical monster, Tasiwa, once lived. That monster killed and ate the Indian people until two orphan boys killed it. Haas collected an earlier version of that story from Yuchigant, but with no mention of the cave.

Both Ana Juneau and Merlin Pierite knew some of the tribal songs such as Run Dance (sung by the men and boys on the way to play stick-ball), Horse Dance, Double-header Dance, Midnight Dance (Elowhara), and others. Harry Broussard, himself a former blues man, recalled fragments of songs collected from his mother, the late Clementine Pierite Broussard, by Claude Medford and later by Gregory. Today, Donna Pierite and her grown children Jean Luc and Elizabeth carry on the traditional storytelling and songs of the Tunica-Biloxi tribe.

So, like the Jena Band of Choctaw, the Tunica-Biloxi retain a number of tribal folk traditions. They, too, have traditional herbal remedies, and practiced their traditional religion at least in part until the 1940s. Their most sacred ceremonial was the Fete du Blé or Green Corn Feast. They held such a public feast in July 1988, integrating a festival/tribal pageant, a Roman Catholic outdoor Mass, and a private ceremonial for tribal members only. At sunrise on July 3, the elders assembled the men and boys and each family carried packages of parched corn to the graves of their families, "feeding the dead" as they always had done. The corn had to be delivered before dawn. The packages, once folded corn shucks, were made of aluminum foil and each had to be carefully opened for the dead to come and eat from them. Ritual baths prescribed by their tradition were neglected because a dam which held water for such a ritual had washed out and a protracted drought had raised pollution levels. In spite of acculturative influences, the feast remains very sacred to the tribe, and the traditions are still practiced by some families. While the Tunica-Biloxi now host an annual pan-tribal powwow as Plains tribes do, many families maintain their own traditions in private.

The Tunica-Biloxi retained their craft traditions into the 2000s. Sisters Ana Juneau, Rose White, and Norma Kwahjo worked at basketry and Ana made traditional dolls. The basketry was coiled pine straw with a unique Tunica-Biloxi style. The ladies learned the craft from the Coushatta, but their mother Rosa Pierite remembered having been taught the craft as a young woman. Cane basketry was still made at Marksville by the late Alice Picote until the early 1960s. Tribal leaders have evidenced a strong interest in reviving the basketry and traditional ceramics.

Aside from the Jena Band of Choctaw and the Tunica-Biloxi, Indian communities are absent from the Delta today. Still, as has been pointed out, those groups know and influence the Delta still. In 1987, the tribal chairmen of the Jena Band and the Tunica-Biloxi Tribe carried their lawyer to the Monroe city council to protest the destruction of a burial mound and a temple mound in a planned subdivision. The tribes won, and a plaque remembering the Tunica and Koroa was placed in what is now a green space in the area.3

Other Indian influences, usually made by isolated individuals, are harder to detect. However, in the western fringe of the Delta area in the Catahoula Basin, the Bouef River area, along Black River, and up the Ouachita River, one meets people with strong Indian heritage. Many of these families trace back to Indian ancestors and point out that they retain a number of Indian characteristics. Moreover, they point out that they have kept back a number of "Indian ways" as well. As late as the 1960s, people at Larto Lake and Big Island told bitter stories of having their people rejected at the Natchez, Mississippi, hospital because they were "Indian-looking." Others noted that their Indian looks kept their traditional heritage alive for them. Some are French-Indian families derived from the interaction of early French traders and settlers with the Choctaw, Biloxi and Pascagoula Indians settled near the Rapides Post (modern Alexandria). Surnames are French—Deville, Sanson, Belgard, Chevalier, LaPrairie, Charrier, Pecanty, and others.

The origins of these mixed-blood communities and individuals are complicated. Most seem to trace back to Choctaw groups, a few still claim Natchez, and others just do not know. Traditions of polity, chiefs, or tribes no longer exist among them. Cherokee ancestry is more often claimed in the Bouef River country, where many early settlers came from Tennessee and the Carolinas. Like the people of Appalachia, these Indian roots are symbolically alive and well in the region. An enclave existed in the Boeuf River/Big Creek country of Franklin Parish with families from Mississippi and Tennessee, likely Cherokee and Creek with possibly a few Choctaw among them. Duncans, Hamptons, Lewises, Herrons, Porters and other Anglo-American names dominated there, but both Indian cultural and racial characteristics set them apart from their neighbors. Until the Great Depression, most of these families lived by hunting and fishing, with some cutting timber. Many preferred to live in isolated places in the woods, keeping contact with more dominant white populations at a low level.

Hunting and fishing were the major economic developments in these backswamp regions, and until recent land developments, most of the people subsisted by farming small acreages and running open range livestock. Swamp lore—hunting and fishing techniques, woodslore, and "savvy"—are often attributed to the Indian identity of the families. Albert Oneal of Deville, Louisiana, put it simply: "When I was a young man, we'd take a horse and ride clear across the swamp to Black River. We never got lost, I don't know why, but we never did. Mama used to say it was because we were part Indian. I just know that we never got lost."

Louis White of Eva, Louisiana, made a similar reference to his brother-in-law from the Boeuf River region: "He's Indian. Once while we were hunting, I heard Calvin talking. I thought we were by ourselves so I went to see who it was. There he was setting on one end of a log, talking to a big boar coon sitting on the other end of the log— in broad daylight. He's that kind of hunter."

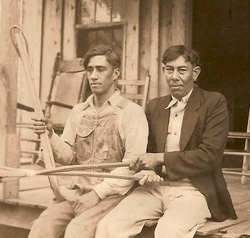

Material culture is not always as definitive. One Cherokee descendant in LaSalle Parish, Curtis Lees, preferred to make "Indian things" so he did beadwork, made feather headdresses, and often dressed up "Indian style." Still, Lees made bows of Honey Locust, switch cane arrows (to which he attached stone points he found or made), harpoons, boat paddles, cane blowguns with pine darts, and turkey tail fans.

These latter crafts were once widespread in backcountry settlements. Along with dugout canoes, they left a definite Indian element in many households, and though they spread to non-Indians, the process of manufacture did not. In each community, a craftsman who recalled traditional methods of manufacture seems to have taught only a special few people how to do his or her craft. Unfortunately, these traditions are being lost. Curtis Lees complained that "people don't recognize these things as Indian," so that complicated the sale of them to a non-Indian audience. He had to "dress up" his crafts as well as himself in more pan-Indian stereotypical fashion. In most of the Delta, this has not happened. What Indian crafts are passed down are strictly family matters, things destined for home consumption and seldom seen at fairs or festivals. Although people may know they are making something "the Indian way," they do not attempt to exploit those crafts. As material culture changes and transportation improves, these crafts are becoming scarcer and scarcer. Worse, nursing homes have tended to repress the manufacture of traditional crafts. For example, one old-timer at a nursing home in Franklin Parish had to hide his pocket knife on a window sill. Others reported they did not make anything other than from kits.

Old-timers who made toy dugouts of cypress or cedar, carved duck decoys, cane blowguns, boat paddles, netting needles, hickory/pecan bows, toy knives, switch cane arrows, notched "scoring" sticks (used to keep count of birds killed, fish caught, etc.), and white oak baskets have had little or no encouragement. Now, most of the people are octogenarians and disabled. Obtaining raw material, as well as access to tools in institutional surroundings, is more and more difficult. Serious efforts to concentrate on these problems have to be developed and were once addressed by the state folklife apprenticeship program, but grants for artists are now as hard to find as the arts they preserved. Crafts like making turkey tail fans need to be maintained, as does the traditional brain (or egg) tanning technique. These existed in the broader context of Indian/white contact all across the Delta area and should not be viewed as necessarily "Indian" or "non-Indian." They should be viewed in their traditional contexts where, in some cases, their symbolic value as Indian identity markers can be preserved without having to pervert them into pan-tribal forms. Symbolic Indian cultural identity must become as important to folklorists and anthropologists as race or polity.

African American and Indian contact seems less frequent than Indian/white contact. There are a couple of reasons for this, the most important being demographic. African Americans were concentrated on the plantations, which were located on the "front" lands, mainly along the Mississippi. They were enslaved there and remained there as freedmen, then sharecroppers and tenant farmers. Poorer whites and Indians held fiercely onto the backswamps and frequently African Americans were excluded from those areas. Virtually every Delta parish had such areas, and "lines" beyond which black folks were not welcome. Whites and Indians lived peaceably alongside black sharecroppers, but the back country became dominated by white/Indian families.

Despite social separations, some African American families in the Delta claim Indian connections. Many carry the nickname, "Red," a term heard into the West Indies for mixed-blood blacks. Like their white-Indian neighbors, these people lived in the swamps whenever possible. Most who worked on plantations became stockmen or field bosses. Women usually worked as house servants. Their roles, like those of mixed white and African American descent, were defined racially. It is likely that much of traditional Indian culture passed into African American folkways through this marginal group.

Foodways in the Delta were heavily influenced by Indian food traditions. Corn foods like cornbread, hominy, grits, mush (called coush in the Tennessee fashion), parched corn, and boiled or fried dishes were staples. Waterfowl including duck, quail, heron or gros bec, bec croche or wood ibis, snipe, robin, and dove were all hunted. Most still are, either legally or illegally, by Delta native peoples.

Deer were hunted for sport by Anglo-Americans, but more for hides and food by the marginal peoples. Night hunting, still hunting (dogs were forbidden), and other techniques were used to take deer. Men would be waiting at dawn and when the deer returned from foraging, they would shoot a doe or fawn for tender meat and leave the others alone. The hides were tanned Indian fashion, using brains or chicken eggs as a tanning solution. Smoked with corn cobs, hides came out a mellow golden brown.

At Stock Landing on Catahoula Lake, the Sanson family continued to build cypress log dugouts or pirogues until the late 1930s. Punt-ended, those boats were more Indian than the sharper pointed versions seen further south. A very fine example of their work is in the museum at DeSoto National Park at Hot Springs, Arkansas. These cypress dugout canoes—not the tiny pirogues but sizable boats—have disappeared. Emerick Sanson was one of the last active builders. His family, of French and Indian descent, lived on French Fork of Little River since the 1700s. His round adze was forged from a French cane hoe made at the colonial post at the rapids on Red River. He still used the traditional cross-wedging to keep the handle in place and used an English foot adze of more recent origin. Young family members learned to carve toy dugouts of cypress or cedar. They not only learned the forms, but the basic mechanics of boat building as well. What was done with a pocketknife was much like what was done with the adze.

Herbal medicines and remedies were passed through all the families. Plant curatives were especially important, and some families kept notebooks and scales for weighing proportions of herb mixtures. During the Civil War, the mixed-blood "doctors" rode circuits, treating families of whites and blacks. These "doctors" were highly respected and are still spoken of heroically. Stories of fantastic cures, even for cancer, still circulate in the Delta.

Today, the Jena Band of Choctaw and Tunica-Biloxi are the only tribes left in the Delta, but the mixed-blood populations persist and protect the cultural landscape. Archaeologists are most times turned away by the mixed-bloods who still keep the Indian places safe. Archaeological investigations near Liddieville in Franklin Parish were met with the old-time Indian complaint: "No, I didn't go look. You know I don't approve of that, them digging up those people. You know they're part of my people. We're all part-Indian here. " The old connections seem more persistent than one would believe.

Notes

1. See Keeping It Alive: Mary Jackson Jones and Herman Jackson's Apprenticeship on the Choctaw Language.

2. See The Hub Lake Gold: An Analysis of A Legend for a version of one of these legends.

3. After Hurricane Katrina, when the state sought to load contaminated trash from New Orleans on Delta land, the Tunica-Biloxi and Jena Band of Choctaw successfully put a stop to the project.