Introduction to Delta Pieces: Northeast Louisiana Folklife

Map: Cultural Micro-Regions of the Delta, Northeast Louisiana

The Louisiana Delta: Land of Rivers

Ethnic Groups

Working in the Delta

Homemaking in the Delta

Worshiping in the Delta

Making Music in the Delta

Playing in the Delta

Telling Stories in the Delta

Delta Archival Materials

Bibliography

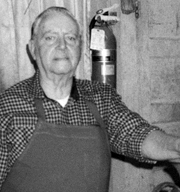

M.J. Varino

Ouachita Parish

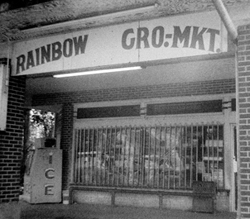

M.J. Varino began working in his father's Italian grocery, Rainbow Grocery, when he was in high school.

Sausage Maker M. J. Varino

By Stephanie Pierrotti

Editor's Note: In 1994, Stephanie Pierrotti, a field worker for the Delta Folklife Project, interviewed Marion John "Mike" Varino to learn about the Italian sausage he made in his Rainbow Grocery. At the 1996 Louisiana Folklife Festival in Monroe, he demonstrated his sausage making tradition on the foodways stage. He continued to run the store and make sausage until 2000, when he retired at age 81, because of failing health. He and his wife lived with his daughter Carmella until his death on August 22, 2005. While the store is gone, Pierrotti's description here provides vital documentation of an important neighborhood institution and folk tradition-Italian sausage making. His son, now living in Kenner, continues the sausage-making tradition and sends it to his siblings and others in the Monroe area.

One of the premier early Italian groceries in early Monroe, the Rainbow Grocery was established by Joe Varino in 1932. Born in 1919, his son, M. J. Varino, began working at his father's store when he was in high school. The young Varino attended Northeast Louisiana University in Monroe for a year and served in the U. S. Air Force in World War II, where he became a fighter pilot, flying over 100 missions for which he received numerous medals. After his tour of duty, he returned to Monroe and the family's Rainbow Grocery, which he eventually owned and operated.

The Rainbow Grocery, located at 4200 South Grand Street in Monroe, Louisiana, was a simple white and red brick building with an awning in front. A faded old sign, "Rainbow Grocery & Mkt," hung over the entrance.

The interior of the building was much longer than its width. Varino said that this was how they used to build stores back then. Nowadays, builders make them much wider. The high ceilings gave a feeling of spaciousness to what is really not a very large building. Wooden hand-made shelves held all sorts of items: canned goods, snack foods, cleaning supplies —all typical, small-store stock. High above them were string held advertisements dating from 1940 to the present. Along the left wall were coolers and freezers holding produce, dairy products, meats, and soda pop. The front counter, old and handmade as well, and an old-style (non-computerized, 1950s era) cash register sat in the middle. Behind the counter were tobacco products on the cigarette shelf hanging from the ceiling on a light chain.

People, whom Varino knew personally, came from the neighborhood to buy little things they need; children came to buy candy; aids from the nursing home across the street came in to get cigarettes. His largest clientele came for Varino's homemade sausage. Hunters sometimes brought in game such as venison for him to make it into sausage.

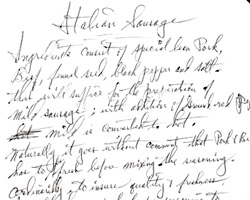

His specialty, however, was his Italian sausage, which in 1994 he had been making for about twenty years. He learned the process by watching his friend Father Sam Pollacia, who passed along the recipes he learned from his family. Varino picked up the recipe, and his sausage has been a very popular item since.

He made, on average, a hundred pounds a couple of times a week, and people bought it as fast as he could make it. The holidays were his busiest time because people bought the sausage for parties and dinners and also sent it to friends and relatives as Christmas gifts. Around Christmas, Varino made as much as 300 pounds per day.

Varino never scheduled his sausage making in advance. He did it whenever it was necessary and didn't really plan ahead. The first step in the sausage-making process was preparing the meat. Varino used pork and beef in the recipe, ratio 2:1. He cut the 80% lean meat into pieces small enough to be fed into the meat grinder. Varino's assistant began his preparations. He opened a large can of tomato juice (about a quart) and divided the contents into four quart jars. The tomato juice, then, filled up about a fourth of each of these jars. He then filled up the jars with water. This would make the juice to water ratio about 1:3. While the assistant was doing this, Mr. Varino said that the real secret to the sausage was the seasoning, especially the fennel seeds. He went to the front to grind up the fennel seeds —he said that grinding them up released the flavor and was better than adding them to the seasoning mixture whole. When he finished, he weighed and measured by sight each of the following seasonings: salt, black pepper, and fennel seeds. He said that this was the seasoning for the mild sausage. His hot sausage also contained red pepper. He then shook the seasonings together in a plastic container to mix them. His assistant poured this seasoning and one jar of the diluted tomato juice over the meat that was to be ground.

The assistant had large plastic tubs waiting in the sink. He cleaned out the grinder, placed the first tub under the spout, turned the machine on, and began feeding the seasoned meat into it. He did this until all the meat had been ground. The whole process took about 30 minutes, and filled three plastic tubs.

The next step was to get the meat into the casings. Varino used natural hog casings as opposed to synthetic ones because, according to him, they have a better flavor. The grinder was the same machine used for getting the ground meat into the casings. A tube, approximately four inches long, attached to the exit-end of the grinder. Then the long string of casing was rolled up until all of it has been rolled onto the tube. Once the casing is in place, a knot was tied at the very end. Otherwise, the meat would just spurt through the casing and onto the floor. Then the ground meat was fed back into the machine, which squeezed the meat through the tube and into the casing. The person operating the machine controlled by hand the speed at which the casing was pulled off of the tube as meat is squeezed into it. If the operator was too slow, the meat would be too densely packed into the casing and the casing would burst during the linking step of the process. If the person was too fast, there would not be enough meat in the casing, which would look unappetizing. Once a length of casing had been filled, the other end of it was tied off to hold in the meat. The assistant was quite fast at making the links. He took the entire length of casing about two feet long and completely filled with meat and laid it out on a counter with the two tied-off ends together. Once he had made the first knot and thereby created first links, he would twist the casing into sections about 4-5 inches long. After the sausage was linked, he divided it into two-pound portions and wrapped it up, ready for sale.