Other Shreveport Articles

Cultural Preservation: Keeping the Flame Burning for Future Generations

Seasons and Cycles — Festivals and Rituals Mark Life's Rhythms

Of Hand and Heart: Handwork Connects Family and Community

Shreveport's Greek Community: Cultural Treasure Spanning Generations and an Ocean

By Laura Marcus Green

St. George Greek Orthodox Church: The Heart of Shreveport's Greek Community

Shreveport's Greek and Greek-American citizens are a venerable and longstanding cultural community. Greeks arrived in the area at several pivotal moments in history, leaving behind the economic and political hardships wrought first by the Greco-Turkish War in the early 20th century and later by World War II and the Greek Civil War in the mid to late 1940s. The invasion of Cyprus in the 1970s brought the last wave of Greeks to the area.

The first settlers to arrive in Shreveport established a Greek Orthodox congregation in 1916, meeting first in an Episcopal church and then in a house on Hope Street. In 1935, the congregation built St. George Greek Orthodox Church in its current location in the Highlands neighborhood. At the time, the church was the focal point of Greek culture and community in the area. Today, many community members live further from the church, but St. George remains the heart of the Greek Community. St. George's congregation encompasses several generations, including the children of the original Greek settlers, who are now the church's eldest members.

To perpetuate their culture among their children and grandchildren, early St. George congregants organized a Greek School at the church, where the priest taught weekly language and culture classes. The Greek School is no longer in session, but young people and adults alike connect with their cultural roots through participation in adult and youth dance groups, among other activities. In recent years, the St. George community has hosted the Greek and More Cultural Festival. At the festival, the public can watch (or participate in!) traditional dance and partake of Greek culinary delicacies prepared by community members. The festival takes place at the church, where in addition to learning about St. George's rich history, visitors can see the building's recently completed expansion and renovation, which include new icons and an elaborately carved wooden altar screen.

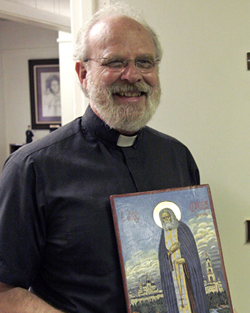

Father Brendan Pelphrey has been the priest at St. George since 2004. The church's remodeling was completed on his watch, in consultation with the church community. As St. George's priest, Father Brendan is the steward of a remarkable collection of artifacts and photographs that tell the story of its congregation and the church's place in Shreveport's cultural landscape. Older congregants can look around the church and see their personal and community history. One congregant, now in his eighties, was the first person to be baptized in the baptismal font that dates from the 1930s. Father Brendan believes that some historic artifacts are integral to worship and the church's heritage, and should be kept in active use. He plans to devote a room of the church's activity center to creating a museum that will preserve St. George's story for future generations.

Sensitive to the congregation's deep connection with the church, Father Brendan struck a delicate balance between making changes in the building and keeping some things the same during St. George's renovation. For example, during the structure's construction in the 1930s, Greek stonemasons helped build the church; the work is exemplary of Greek skill. For the church's recent remodel, it was hard to find craftsmen who could replicate the historic Greek masonry. St. George worked with Italian stonemasons who hired Mexican workmen to help build the church additions. During the expansion, they saved the historic limestone pieces carved with crosses and reset them or replicated them in some cases.

Georgia Booras attended the Greek School when she was a girl. Her mother emigrated to Louisiana from Greece in 1951 and her father's family were among the first Greeks to arrive in Shreveport during the early 1900s. She reflects, "St. George is my home church—I was raised in this church." Georgia's paternal grandparents died when they were relatively young. Their sisters and brothers lived into their nineties, however, and were like grandparents to Georgia. Throughout her childhood, she enjoyed spending time with the immigrant generation of her father's family. Remembering her elders, she says, "They all had special places that they would sit in church, and they sat in that same spot every Sunday." For Georgia, the church is brimming with memories. She remembers the initial jolt of the church's remodel, when walls came down and icons were removed for the renovation. Each week, Georgia and her family came to check on the progress. At the time, she recalls,

everything was empty, and I thought, well this isn't my church. What have they done to my church? Your heart kind of sank because you thought, everything you knew was gone. But then you realize after it's all done, the beauty of it. It's just made it that much more beautiful. The church feels more open and the choir sounds better now. And you know, all the memories are still here.

Currently, the congregation includes Russians, Ukrainians, Serbians, Romanians, Bulgarians, Egyptian Copts, Ethiopians, Indians, and Palestinians, among others. Some of St. George's Arab Palestinian families have lived in Shreveport for two or three generations. Administering to a diverse congregation, Father Brendan notices both similarities and differences among its members, based on people's cultural, historical, and generational experiences. In many aspects of his work, he tends towards a traditional interpretation of Greek Orthodox practice, while ensuring that the church remains meaningful and relevant to all congregation members. Father Brendan incorporates both Greek and English languages in his services, for example, maintaining liturgical practices that span centuries, while grounding his sermons in contemporary themes.

Like many features of its interior, the church's architecture is itself symbolic. Father Brendan elucidates the church's structure as it relates to Orthodox practice.

It has three distinct parts, and each part has its own functions. So the outer part—the entry to the church—[is] for repentant prayers, lighting candles for prayer for others, things like that. You come into the inner part if you've fasted and prepared yourself. Only priests and the altar servers go into the third part, which is the holy place from the ancient temple. The altar area is the church's most sacred space. Father Brendan explains that this area is for congregants like Heaven itself—you can look in but cannot enter.

The ancient temples on which Orthodox churches are modeled had a curtain and wall that separated the church's inner part from the altar. St. George's altar screen or gateway was part of the church's renovation. It was hand carved from red oak by an artist in New York. The choice and order of the icons in the gateway are determined by Orthodox practice. Altar screens vary depending on their size, but they always include Jesus Christ, Mary, the church's patron saint (in this case, St. George), and the Archangels Michael and Gabriel.