Other Shreveport Articles

Cultural Preservation: Keeping the Flame Burning for Future Generations

Seasons and Cycles — Festivals and Rituals Mark Life's Rhythms

Of Hand and Heart: Handwork Connects Family and Community

Mexican Home Altars and Día de los Muertos Traditions: Finding the Way Home Through Art and Heritage

By Laura Marcus Green

Like many New World phenomena, Día de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead, reflects a combination of cultural influences, including centuries-old, pre-colonial, indigenous commemorations of departed ancestors, and the Catholic observance of All Saints Day on November 1st and All Souls Day on November 2nd. In parts of Mexico, Día de los Muertos holds the status of a bank holiday. Ofrendas or altars might be set up at the actual gravesites of loved ones, at community spaces like churches, schools or community centers, or in people's homes. Under different names, Día de los Muertos is also celebrated in some other Latin American countries and in Spain.

In creating ofrendas, people are inviting their loved ones to return for a visit, to partake of favorite foods or other items they enjoyed in life, and to know that they are not forgotten. Ofrendas are personal expressions of who people were in life, through the offering of favorite foods and beverages and the display of photographs or special mementos. Decorated skulls made from sugar, called calaveras, and pan de muerto (bread for the dead) are prepared at the time of Día de los Muertos and placed on people's ofrendas. In U.S. cities with sizable Mexican communities, there are often large-scale celebrations with public installations and processions or other gatherings. Regardless of the scale or format, the idea is the same. Some larger scale, public Día de los Muertos U.S. celebrations may also take on political significance, as celebrants imbue their observances with social commentary. As Shreveport-Bossier City's Mexican and Latino populations have grown in recent years, annual Día de los Muertos celebrations at various public venues are taking root.

Conchita Iglesias McElwee's heritage and art reflect a fascinating crossroads of cultural and aesthetic influences. She is named for her great-grandmother, Maria de la Concepción Coríz Pacheco Iglesias, who was known as Conchita. Conchita Iglesias McElwee's great-grandfather, José Iglesias, was raised by the Catholic Church in Spain, after his family gave him up for adoption when he was a baby. At 14, when he was facing mandatory military service, the priest at the church sent young José to Mexico, rather than have him serve. In Mexico, he ended up working on the elder Conchita's family's land. Defying social conventions, José and Conchita fell in love, married, and moved to Louisiana, first to New Orleans and then to Shreveport in around 1926. The couple had two children, Juan Jorge and Yolanda. While José worked at the Libby glass factory, Conchita helped support the family by selling tamales downtown. Sadly Conchita died in her mid-forties, when her son Juan Jorge was only 15 years old. Juan Jorge eventually married Gloria Dale Parker, a descendant of the well-known Comanche leader, Quanah Parker.

The granddaughter of Gloria and Juan Jorge Iglesias, Conchita Iglesias McElwee traces her family heritage as Mexican/Mayan, Native American, and Spanish. Gloria Iglesias' conversion to Mormonism in the early 1960s led the family to extensive genealogical research, part of the Mormon tradition. Conchita says that she was raised in libraries and cemeteries. Her family tree goes back 25 generations. Conchita's understanding of her family roots has nurtured her quest to know her cultural heritage. During her childhood, Conchita lived on and off with her grandparents, to whom she was very close. Although he was born in the U.S., Juan Jorge-whom Conchita knew as Papaw-made regular trips to Mexico, where he visited family in the Federal District and Guanajuato. Her grandfather's return from these trips were a highlight of Conchita's youth, as he would bring home a suitcase full of Mexican delicacies including cajeta (goat's milk caramel), which Conchita considers "gold in a jar." The family would gather to share vanilla ice cream topped with cajeta. Remembering those times, Conchita says, "It was like tasting Mexico."

Her grandfather's food and his music were among the Mexican flavors Conchita got to savor as child. She grew up hearing his favorite music-old Mexican and Tejano country, slow boleros, and singers like Vicente Fernandez and Julio Iglesias (especially when he sang with Willie Nelson!). Conchita regrets that her grandfather did not teach her Spanish. When she was in her early twenties she asked him why he had not done so and he responded that he didn't think she would need the language living in Shreveport, where there were so few Latinos. Her grandfather's decision reflected cultural dynamics at the time. Conchita relates that during her childhood and before, Shreveport's predominant cultures were African- and Anglo-American. Her Latino family was considered to be very different. Speaking Spanish and displaying your Latino heritage were things you kept at home, to yourself. Conchita was in high school before she encountered a Latino classmate.

Having grown up in Shreveport when there were few other Latinos in the area, Conchita has been keenly aware of the growth in the Latino community over the last fifteen years. Her career as a social worker gives her firsthand insight into who is coming to the area, from where they are coming, and why. Conchita believes that the construction of casinos was the first draw that brought people from neighboring towns like Tyler and Marshall, Texas for work. Further, as post-Katrina rebuilding work is drying up, people are coming to Shreveport-Bossier City, where jobs are more plentiful. As the Latino infrastructure grows in the area, people are more inclined to settle there. Conchita sees the expansion of Shreveport-Bossier City's Latino and other ethnic communities in the proliferation of multicultural stores and restaurants that are appearing around town. When she was growing up, her grandfather traveled as far as Austin, Texas to find a Mexican grocery store.

Conchita believes that her creativity may be genetic. Her great-grandmother Conchita did handwork. Conchita the younger has a piece of embroidery that her great-grandmother made eighty or more years ago. Her grandparents, Juan Jorge and Gloria Iglesias, spent a lot of time working on ceramics around the kitchen table. They also did papier mache, which Conchita loved when she was a child. Conchita's mother is a talented painter. Yet it wasn't until she was in her early twenties, working in children's services, that her own creative spark was lit.

Conchita remembers working with small children who had been taken from their homes. She learned that the fastest way to reassure these frightened children was to take them aside to color and talk, not about the situation that brought them to her, but about their pictures. Coloring put the children at ease. Doing art activities with the children became a regular part of her work with young people. She soon recognized that art was also a means for her to wind down at the end of the day. She began working in mosaics and then took up painting. This juncture in her life coincided with her growing interest in Mexican art and culture.

As she grew older, Conchita began researching her Mexican heritage. She avidly read about luminaries of the Mexican art world like José Clemente Orozco, Frieda Kahlo, and Diego Rivera. The work of José Posada, an early-twentieth-century Mexican printmaker whose Lady Catrina figures have become emblematic of Día de los Muertos, was a happy discovery for Conchita as she explored Mexican art and culture through books and National Geographic articles.

Conchita's ofrenda is among the Mexican traditional art forms she has embraced as an adult, drawing from her memories of her grandparents' home. Now an important part of her personal and artistic life, ofrendas were a muted but powerful presence in her grandparents' home when Conchita was growing up. She remembers her grandparents' special shelves that were not called an ofrenda, but their meaning was understood. Conchita recalls,

That's where all the pictures were, and the little mementos . . . you kind of always knew that that was like the reverent space. There was an acknowledgment that that's what it was, you didn't touch it. That was a memory space. But no, my grandfather didn't call it an ofrenda. I think if he would have called it anything, it would have been a shrine or something like that. I think ofrenda is really a word that came into my life much, much later as I began studying more about Mexican culture.

Today, Conchita keeps many of the things from her grandparents' special shelves on her home ofrenda. Having inherited these treasures at her grandparents' passing, she is the steward of her family's history and heritage, which she now explores and practices openly, sharing it with others through her artwork.

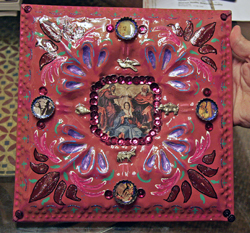

Conchita's ofrenda is made from a bureau that she has customized by painting it with colorful flowers on a pink background. The front of the ofrenda shimmers with glass pieces and bottle cap saints' pictures that she has affixed to the front of the shelves. The ofrenda holds all manner of memorabilia: family photos, saints' candles and other representations, Calaveras (sugar skulls), mementos, a candelabra set sent to her grandparents from Mexico on their 10th anniversary, and a bust of Elvis Presley-a tribute to Conchita's Shreveport roots and musical taste. Below the display, the bureau drawers contain arts supplies. As Conchita puts it, "You can't have enough storage when you are an artist."

In addition to creating ofrendas, Conchita makes other traditional arts associated with Día de los Muertos, including calaveras and papel picado, delicate paper cut-out banners. She traces the calavera tradition back to Mesoamerican cultures, in which ancestry was very important. From her research, Conchita learned that people would keep skulls in shrines and religious spaces in their homes. When the Spanish Catholics arrived in the area, they frowned upon this practice and told people to bury the skulls. So people began making skulls out of sugar cane, which abounded in the area. They processed and molded the sugar cane, decorating the skulls with little pieces of colored foil and colorful icing. This practice continues today. People often write the name of the person in icing and add personal attributes like moustaches and glasses to the calaveras. Generally, each skull represents a particular person.

Papel picado is another Mexican tradition that Conchita incorporates into her own and community art installations. She believes that papel picado's origins might be in Mexican wedding day festivities. She taught herself to make papel picado by looking at it and saying, "I can do that." Cutting small holes in fragile pieces of paper to make lacy patterns is time-consuming, a labor of love. Conchita makes papel picado for shows and special community events. She remembers being especially taken with papel picado she saw on one occasion in San Antonio, Texas, made from gold paper. "It just moved with the air . . . there's nothing so beautiful. It's so simple but it's so beautiful at the same time."

As she researched her Latino heritage, Conchita found both similarities and intriguing contrasts between her Mormon upbringing and her Mexican indigenous and Catholic roots. On one of his trips to Mexico, her grandfather brought her a book about Pre-Columbian and Mesoamerican art and the Incans. She recalls that the book opened her to a new way of seeing things:

That's where I discovered Day of the Dead. And the way that I read it, what drew me into it initially was that it was part of a cycle of life. That it was, not that life ends, but that at some point, yeah we become bones but we're still just as relevant as bones as we are as living, breathing people. You know, that you still need to be acknowledged by your family and you'll live on, no matter what. And I just thought that was amazing. And I think part of it is that genealogy and history in my family, you know, the acknowledgement of ancestry as always being a part of your life.

Whereas the Mormon Church does not espouse visual symbolism, the Catholic Church abounds with imagery and color, a tradition that Conchita has wholeheartedly embraced. An early interest in Joan of Arc led her to learn more about Catholic saints, a further source of wonder and inspiration. She recalls being captivated by the Catholic notion of sainthood. "Just, the whole thing that is Catholicism is very interesting to me. The fact that man can become more than that, more than what we're born."

Another eye-opener in Conchita's life was her visit with local artistic legend, Clementine Hunter, whose home on a plantation in Natchitoches remains open to the public. When Conchita was around seven years old, a National Geographic article about Clementine Hunter caught her eye. Conchita asked her grandmother if they could go visit Hunter, a request her grandmother obliged. At the time, Hunter was in her eighties and still painting. Conchita remembers being struck by a painting hanging above Hunter's sleigh bed, of Jesus and angels, all depicted with brown skin. This made an impression on Conchita who, up to that time had only seen Jesus and angels portrayed as white. Further, unlike Mormon angels, Clementine Hunter's angels had wings. Conchita remembers saying to the elderly African-American artist, "But angels don't have wings." Hunter's response was, "Angels have whatever you want 'em to have." Young Conchita not only admired Hunter's artistic talent, but she internalized some of her independent spirit.

If art work provides Conchita with a way to relax, it is also a vehicle through which Conchita delves into complex social and personal issues, from immigration and citizenship to her own cultural identity. Drawing on her grounding in Mexican traditional arts, Conchita also finds a creative outlet through more contemporary installations in which she combines painting and collage. She is especially fond of upcycling, or repurposing recycled objects like bottle caps, pop cans, and other items. Even this approach is inspired by her admiration for the tradition of Mexican ingenuity she has seen in reinventing found objects to become something better than they were.

Conchita has displayed her combined traditional and contemporary work at various venues around town, like the Shreveport Regional Arts Council's artspace and the Multicultural Center of the South. She feels a special affinity for her artist cohort at minicine, an arts collective and presentation space located in the heart of Texas Avenue. The area was once the neighborhood where Shreveport's immigrant communities lived and is now being rejuvenated as an arts and cultural district. Conchita's involvement with the local arts scene represents a commitment. She says, "If you don't do it, then who's going to do it? It's just a part of this community. We've just built so much and I just want to add to it as much as I can."

Conchita relates to Chicano art, which she feels has always been informed by its Mexican roots. Regardless of the piece she is making or the themes she is exploring, her artwork continues to call her home to her heritage.

For me, it's a personal journey to find me. Because I was the kid that wasn't white. I wasn't Black. People thought my name was funny, but they thought it was pretty. I knew that my family was different, but I didn't have another frame of reference outside of my family. This is me, finding Conchita. It's me figuring out, okay, if I would have grown up somewhere else, this is what would have been a regular part of my life. And this was supposed to be a part of my life. And I'm mad that it wasn't! If I were to have children, that cycle would be back in their life. I would pick it up like it was part of my childhood. Because I think a lot of things in my childhood, although we were all artistic and crafty and stuff . . . we painted gourds and things like that, but we didn't make piñatas. I would have loved to have made piñatas. Like papel picado, we made the big flowers but we never did papel picado. It's kind of like it was there, but it just needed to go a step further. So now I'm trying to go a step further and have those things in my life, too.