A Better Life for All: Traditional Arts of Louisiana's Immigrant Communities

A virtual, expanded version of an exhibit from the Louisiana State Museum

In collaboration with the Louisiana Division of the Arts Folklife Program. We regret that the exhibit is no longer available for traveling.

There is an indescribable feeling that comes over me when I hear some of the traditional lieder (popular German art songs). Could it be in my genes? I don't really know, except that no other nation's song has the same effect. The German community wants to preserve its history and culture just as every other national group attempts to do the same. We are a melting pot, but we don't have to be totally unrecognizable! Being a citizen of the USA comes first, of course, but we do want to know our roots.

—Gail Perry, president of Damenchor (Women's Choir)

at the Deutsche Seemannsmission (German Seamen's Mission).

Photo: Laura Westbrook, 2008

Traditional Arts of Louisiana's Immigrant Communities

Louisiana is a cultural gumbo, seasoned with many flavors, each adding its unique spice to the stew. For centuries, people have made their way to the Bayou State, known for its hospitable climate, welcoming feeling, and plentiful opportunities. The state map abounds with names like Manila Village and Cote des Allemandes (German Coast), revealing a history and heritage interwoven from many cultures. As new immigrant communities take root, Louisiana's cities and rural areas blossom with their presence on the landscape.

Generations of immigrants have left their native countries to find a home in the Bayou State, motivated by economic, educational and professional opportunity, political freedom and safety, or even a sense of adventure. Throughout Louisiana, a multicultural work force contributes to the hospitality and other industries, agriculture, and clean-up and reconstruction following manmade and natural disasters. Universities, medical centers, and military bases have also attracted many international community members.

Whatever their reason, most immigrants come to Louisiana for a better life, while bringing with them an abiding love of their culture, a connection rekindled and nourished through traditional practices from their home country. Whether part of everyday life or special occasions, traditional foods, music, dance, crafts, and rituals and celebrations anchor people in a new home. A Better Life for All invites you to explore Louisiana's cultural abundance through the remarkable range of cultural traditions with which immigrant artists and communities enrich our state.

Continuity and Adaptation, Lanexang Village near New Iberia

Mardi Gras beads signal innovation in Lao Buddhist altar offerings or pod made for Songkran, the Lao New Year celebration, at Lanexang Village, in New Iberia Parish. Traditionally, these offerings contain fruit, flowers, or prepared dishes. The Buddhist temple and Pra-Thard Luang (a stupa or commemorative structure) at Lanexang Village show traditional architectural woodcarving. Lanexang Village was created in New Iberia in the early 1980s by refugees from Southeast Asia. According to community leaders their Songkran festival is both the largest Laotian festival of any kind and the only Laotian Songkran festival held in the U.S.

Blooming Where You Are Planted

United States, Vietnamese, and Buddhist flags wave above the Chua Bo De Buddhist Pagoda, New Orleans. Looking towards Woodlawn Highway, Quan Am, Goddess of Compassion, greets congregants, who often bow their heads before her statue when entering the pagoda. Amidst pink blossoms, yellow plastic flowers are wrapped around branches, recalling hoa mai, a plant that blooms in southern Vietnam around Têt, the Vietnamese New Year, symbolizing prosperity and wellbeing for the family.

Welcome and good fortune to all who enter

Rangoli are special designs made with ground stone, chalk, rice powder, other natural materials, or flowers by women across India, and perpetuated by those living in Louisiana. An ephemeral art form, rangoli is done outside the doors to people's homes or Hindu temples, usually during special occasions. Rangoli designs welcome guests and wish good fortune to those who enter, and create a sacred place for prayer.

for the 2006 International Festival.Photo: Maida Owens, 2006

Immigrant Cultural Communities in the Bayou State

When immigrants are away their homeland, they often cherish their traditions because they are expressions which give them a sense of belonging and link them to their roots.

—Guiyuan Wang, Chinese anthropologist, Baton Rouge

"Immigrant" encompasses a range of experiences as diverse as the people who have made Louisiana their home. Some immigrant communities have been in Louisiana for generations, with successive waves replenishing ties to the home country. Others have arrived more recently. Some immigrants have come in groups, while others arrived as individuals or small family units. Some newcomers are highly trained professionals, fluent in English. Others speak only their native languages and did not pursue a formal education in their homelands. Yet the cultural knowledge they bring from their native countries may be the equivalent of an advanced degree or professional apprenticeship.

The majority of the state's immigrants have come from throughout Asia and Latin America. The largest communities hail from Vietnam, Honduras, Mexico, Cuba, India, Germany, the United Kingdom, and China. Significant numbers also come from Palestine, the Philippines, Nicaragua, Guatemala, Korea, El Salvador, Japan, Columbia, Pakistan, Nigeria, Laos, Thailand, and Nigeria.

The 2010 United States Census reveals that 3.7% of Louisiana's resident population is foreign-born, including some residents who have become U.S. citizens. Most foreign-born residents live in urban settings, with the greater New Orleans and Baton Rouge areas having the greatest number of immigrant communities. Jefferson Parish-encompassing the Metairie, Kenner and West Bank communities near New Orleans-has a population base of 7.48% foreign born, making it the state's most culturally diverse district, with the largest concentration of almost every immigrant community in Louisiana. While 36 out of 64 mainly rural parishes recorded one or less percent of immigrant residents, there are notable exceptions. Vernon Parish, with Fort Polk in Leesville, is 4.13% foreign-born, as many military personnel married foreign-born spouses, who then brought their families to live in the U.S. Another exception is the Laotian community near New Iberia, primarily a rural area. Several other rural parishes across southern Louisiana have culturally diverse communities, but otherwise, most immigrants living in rural communities are Mexican.

You don't truly understand [your culture and religion] until you migrate to somewhere else.

—Mee Mohamed, Mauritian community member, Baton Rouge

Notes to Live By: Musical Traditions

For many of these Cuban immigrants, the only possession they could bring, like a precious gem,

was their culture and music.—Tomás Montoya González, sociologist, Santiago de Cuba

From lullaby to a hymn to national anthem, music carries people home. It is among the easiest traditions for immigrants to share with the broader community, especially in Louisiana, where music figures prominently on the cultural landscape. The state's vibrant musical terrain is fertile ground for musical fusion and exploration. The improvisational spirit of jazz—Louisiana's own indigenous musical tradition, itself a blend of influences—embodies the sense of creative adaptation that immigrants embrace to navigate life in a new home. Some immigrant musicians play in multicultural bands, melding diverse traditions to create new sounds. These same musicians may also provide more "authentic" music for cultural occasions prescribed by tradition. All cultural traditions are dynamic. As people move around the globe, change may prompt them to hold more firmly to the traditions they remember from home, or it may spark creative adaptation.

I had the pleasure of sharing my Garifuna culture, and it was very interesting to integrate the Garifuna music with other cultures here in New Orleans, to share in community making. To share in music, in rhythms with other cultures . . . It was a marvelous form of excellence. It makes me realize that we can shine in this place that is New Orleans.

—José Dolmo recalling drumming with local band, Ecos Latinos (Latino Echoes), at the 2008 New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. José came to work on reconstruction following Hurricane Katrina.

Garifuna Rhythms of Change and Continuity, New Orleans

The Garifuna sing their pain. They sing about their concerns. They sing about what's going on. We dance when there is a death. It's a tradition [meant] to bring a little joy to the family, but every song has a different meaning. . . . The Garifuna does not sing about love. The Garifuna sings about things that reach your heart.

—Rutilia Figueroa, Garifuna elder, New Orleans

The Garifuna of New Orleans are descended from Nigerians who escaped slavery and lived freely among the Carib and Arawak peoples of St. Vincent during the 17th and 18th centuries. In the late 1800s British colonial authorities banished the Garifuna to Roatán Island, directly north of Honduras, where they adopted Catholicism and made Spanish their second language, while retaining their Afro Caribbean roots. Encompassing multiple generations, the Garifuna in New Orleans began arriving in the 1960s, when political and economic instability at home and the city's strong trade relationship with Honduras brought many to the area for work.

A Universal Language: Indian Music, Baton Rouge

Since the 1960s, Indians have come to Louisiana for educational and professional opportunities, settling in urban and rural areas, with the largest communities in Baton Rouge and Jefferson Parish. As the community has grown, India's classical arts have been maintained and performed in Louisiana, fortifying people's lives and deepening the sense of community, while offering others an experience of India's cultural gems. Throughout Louisiana, Indian youth are nurtured in their cultural arts through dance schools and music training, taught by professional artists and community members.

Sitarist Meera Seth of Baton Rouge was among the first musicians to present Indian classical music in Louisiana. She reflects: "Music is a universal language. . . . It's a way of communicating with other cultures. . . . Through music we can tell a lot about the heritage of the culture. Playing sitar all over Baton Rouge . . . I thought that it was my duty to expose Indian classical music to Americans. I became like an ambassador, like a bridge. Then I started teaching, and this gave me the most happiness."

LISTEN: Sitarist Mrs. Meera Seth performs "Bhupali" on sitar, a 25-string lute with a gourd body and wooden neck. Like jazz, Indian classical music is spontaneous, taking a unique shape in each performance, depending on the circumstances and environment in which it is played. An oral tradition, it is typically passed down in formal teacher-student relationships.

Plucking Cultural Heartstrings: Guatemalan Music, Kenner

A Spanish colony in the late 1700s, New Orleans is home to one of the oldest Latin American communities in the U.S. The historic fruit and coffee trade between Guatemala and New Orleans has fostered transnational movement and cultural sharing over the years. Political unrest during the 1960s and '70s brought a new wave of Guatemalans to the city. Brothers and musical duo Julio and César Herrera came to New Orleans as young men in 1967 to attend school. Having grown up in a musical family, they both play nylon-string guitars. César sings and plays rhythm, while Julio picks intricate leads that are evocative of the marimba, a wooden xylophone-type instrument prevalent in Guatemala.

Julio and César Herrera play in restaurants, clubs, private parties, concert halls, festivals and charity events across southeast Louisiana. Guatemalan folk music is their first love, but they broaden their appeal playing salsa, merengue, boleros, samba, flamenco, and country western. While absorbing and playing to Louisiana's diverse musical heritage, the brothers "try to conserve our traditions and that culture."

Culture in Motion: Dance Traditions

Folk dancing is a cure for nostalgia.

—Guiyuan Wang, anthropologist, Baton Rouge

Dance traditions flourish in immigrant community life at private family celebrations, nightclubs, and large-scale public festivals and performances. Some dances are vernacular or popular traditions, such as Latino salsa or ballet folklorico. Others are folk dances, like Greek dancing done at weddings and other festive occasions, or classical or court dances such as Indian Bharatnatyam. Deeply rooted in history, traditional dances impart public and private statements about cultural heritage and values, bridging the different worlds in which immigrants live. According to Guiyuan Wang, "Every performance is a package of the traditional music, clothing, life style, customs, aesthetics, and symbols of a people in their regional, social, and natural settings."

Balancing Between Worlds: Filipino Tinikling, New Orleans

As far as the social heritage, [we have] had to preserve it as Filipinos. We had to be successful in the general population and also to remain part of the smaller community. It is a balancing act between the public and private life. The thing that would symbolize the Filipinos might be the tinikling—the dance between the bamboo sticks, learning to move in and out of the two worlds with good grace, courage, and humor.

—Marina E. Espina, New Orleans, first female president, Filipino-American Goodwill Society of America, and founder, Asian Pacific American Society

Filipino sailors and navigators traveling on Spanish galleons began arriving to Louisiana's coastal waters in the 1760s, where they adapted their seafood-harvesting skills to fishing and shrimping and established "stilt villages"—an architectural tradition adopted by other wetland communities. The last of these, Manila Village, was destroyed in 1965 by Hurricane Betsy. Filipinos continue to emigrate to Louisiana, making them one of the state's oldest and newest populations.

The Filipino national dance is Tinikling, named for a long-legged bird that navigates watery fields and bamboo traps set by rice farmers with agility, speed, and grace. Some say the dance celebrates the Philippines' natural beauty and customs, while others believe it harks back to harsh Spanish colonial days, when slow rice-pickers were forced to jump between thorny sticks. Variants of these origin stories abound! In Louisiana, Tinikling brings joy to community celebrations and public festivals.

Cultural Heartbeat: Greek Dance, Shreveport

Shreveport's Greek community arrived in response to a series of historical events, beginning with the Greco-Turkish War in the early 1900s, World War II and the Greek Civil War in the mid to late 1940s, and the invasion of Cyprus in the 1970s. Second-generation community member Georgia Booras recalls from her childhood, "Greek dance was just something you learned within your family. Whether it was a wedding or a baptism or any kind of family celebration, Greek dancing was just always part of it." The community began sharing their dance traditions at public festivals in the 1970s. Today, Greek dance remains the heartbeat of family parties and an expression of cultural pride, as community members dance in the footsteps of earlier generations.

In the photo above, the Greek Feet youth dancers perform at the 2010 Greek and More Cultural Festival, St. George Greek Orthodox Church in Shreveport. St. George has for generations been the heart of the Greek community and a locus for the preservation of cultural traditions, both sacred and secular.

A Balance of Grace and Strength: Chinese Folk Dance,

Baton Rouge

New Orleans' Chinatown dates from the 1880s. Following the U.S. ban on Chinese immigration (1882 to 1965), more recent Chinese immigrants have come to Louisiana for educational and professional opportunities, living primarily in cities and some rural areas. The Yang Guang (Sunshine) Chinese Dance Troupe of Baton Rouge performs locally and regionally. Their repertoire of folk classical and ethnic dances reflects China's cultural diversity, connecting performers with their roots, while promoting intercultural communication and understanding in their new home.

In the photo above, the Sunshine Dance Troupe performs Peach Blossom at the Spring Festival Gala, Baton Rouge. Based on a classical Chinese poem predating 221 B.C., this folk classical dance includes poses and gestures from Han dynasty brick painting images from 200 A.D. Symbolism abounds: young ladies are likened to peach blossoms; their longing for marriage expressed through elegant, light-footed moves; their future happiness conveyed by blooming peach flowers; their red costumes reflecting Han Chinese marriage customs.

A Taste of Home: Cultural Foodways

A portable form of knowledge, foodways are among the first and most lasting cultural traditions to be established in a new home and maintained by future generations. Ethnic grocery stores and restaurants are often the earliest signs of new cultural communities, as people long for a taste of home and require special ingredients for native dishes. These businesses become community gathering places, and an entry point for others to discover new neighbors through their cuisine. The heart of family and community celebrations, traditional foods bring comfort to daily life. For some, their cultural cuisine may become a source of income or a way to raise money for a community cause.

A Rite of Passage: Bosnian Pita, Baton Rouge

She who wants to be married must do pita."

—Hasan Stranjac, husband of Emira Stranjac,

Baton Rouge

Pita pastry, a hallmark of Bosnian cooking, is among the traditions Emira Stranjac has maintained in her Baton Rouge home since 2000, when her family arrived as refugees from the war in their country. For women of Emira's generation, knowledge of pita-making was essential. In contrast, her daughter learned to make this delicacy simply because she enjoys eating it. The Stranjacs raised their family in the U.S. where, unlike themselves, their children have better opportunities than in Bosnia. Although Emira sees her daughter as an "American girl," cooking and other cultural traditions remain a connection to the family's homeland.

To make Bosnian pita pastry, Emira Stranjac stretches her paper-thin homemade dough over an oklagia. The dough is then rolled out on a card table, cut into strips that are filled with a meat or cheese filling, and rolled into coils for baking.

Wrapped in Tradition: Guatamalan Tamales, Ruston

We always, [in] our culture, use the corn.

It's the base for everything."—Diana Gay, Ruston

Diana Gay's "Guatamales" embody her journey from Guatemala to her adopted home in Ruston, where she married a Louisiana native in 2000. As a child, she learned the day-long process of tamale-making from her mother, but it wasn't until she lived in the U.S. that Diana made tamales, or chuchitos, regularly. Following in her mother's footsteps, she rises early on Christmas mornings to make 100 - 200 tamales. Throughout the year, she makes them for her family, for sale to others, and at educational demonstrations where she shares her love of cooking and her culture.

To make her Guatamales, Diana Gay kneads the corn mix until she feels the right texture, then wraps tamale shells around the corn dough and filling, usually chicken or pork cooked with vegetables and spices. In Guatemala, she used banana, plantain, or other leaves for her shells. In Ruston, she improvises with what is on hand—corn husks. The wrapped tamales are nestled in a deep colander and steamed about an hour.

Diana Gay makes "Guatamales." Photos: Mandy McClain, 2001

Earthly Fare: Vietnamese Bánh Chung, New Orleans

One of the largest immigrant communities in Louisiana, the Vietnamese began settling in New Orleans soon after the Vietnam War ended in 1975. Têt, the Vietnamese Lunar New Year, is the most important holiday, marking the beginning of spring in a country whose strong agricultural heritage spans thousands of years. In New Orleans, Têt remains a time for family reunions and material and spiritual renewal, celebrated with feasting, parties, and a festival.

In New Orleans' Versailles community, Mrs. Mat Pham (Mrs. Vien) makes the quintessential food for Têt, bánh chung, for family and friends. A center of chopped pork and mashed beans is rolled into a sticky rice cake that is wrapped in banana leaves and boiled for twelve hours. The nine-square grid symbolizes the traditional system of village land rotation, with a central area reserved for the common good, giving each farmer access to better and worse soils over the years.

Mrs. Mat Pham makes bánh chung.

Photos: Mark Sindler, 2008, Allison Truitt, 2006

The Legend of Bánh Chung

Three thousand years ago, when King Hung Vuong VI of ancient Vietnam grew old, he gathered his sons, announcing he would bestow his throne to the one who brought him the most delicious food. The princes traveled far and wide seeking the rarest, most delectable foods. The older sons got help from their mothers, but the youngest son received little advice because his mother was dead. One night in a vision, a fairy taught him to make bánh chung and bánh dày. He presented them to his father, explaining that the square, green bánh chung symbolizes the earth and the round, white bánh dày symbolizes the heavens. Impressed by the inherent wisdom in this simple food made with the basic materials of life-rice, meat, beans, and leaves-the king gave his youngest son the throne.

Of Hand and Heart: Crafts and Material Culture Traditions

Crafts and material culture traditions take root less readily in a new country than other art forms. From yarn to hand tools, the lack of necessary specialized materials is an obstacle, although this lack can lead to creative improvisation! Some immigrant artists find that items like handmade shoes or clothes or baskets, once part of life or livelihood in their native cultures, are rendered unnecessary by manufactured goods or a different lifestyle. Even so, the process of making things by hand may in itself be enjoyable, even meditative or healing. Some material culture traditions are maintained in the hands of artists whose passion and dedication provide necessities for community life. Those with this specialized knowledge are treasured in their communities. Their work takes on new value and meaning far from home.

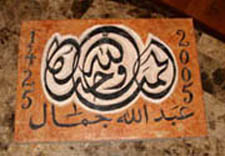

Written in Stone: Arabic Calligraphy and Carving, Baton Rouge

In Palestine, calligraphy is an art form in high demand, with many uses, both sacred and secular. In 1990, while still in his home country, Ayman Zaben apprenticed for one year to a calligrapher and stone carver. Living in Ramallah, he made a living combining these skills to carve stones for homes, mosques, and cemeteries. Having come to Baton Rouge for better opportunities, he applies his skills to machine-cutting stone slabs in a factory job. Like many immigrant craftspeople who once made a living from their art form, he must adapt his talents to life in a new country. His hand-carving and writing are gifts he now shares with his family and mosque, for whom calligraphy remains an important part of the culture.

Ayman Zaben carves stone with calligraphy. Photos: Jon Donlon, 2007

A Labor of Love: Honduran Rococo Embroidery, New Orleans

Historically, Hondurans have been New Orleans' largest Latino community. A strong business relationship between Honduras and New Orleans, based mostly on the fruit trade, has fueled a social pipeline between the two places for over a century. Argentina Colomer, an ESL (English as a Second Language) teacher in the Jefferson Parish School System, incorporates cultural traditions into her classroom, where immigrant students learn to appreciate their own and others' cultural heritage.

Having learned needlework when she was a grade school student in Honduras, Argentina continues these traditions, including rococo, a fine embroidery style used to embellish christening gowns, newborn clothes, and household linens with scrolls and floral patterns. Although not unique to Honduras, in New Orleans rococo is identified with the Honduran community. People treasure rococo for its fine quality and association with home. These pieces become family heirlooms.

Sacred Designs of Hospitality: Indian Rangoli, New Orleans and Baton Rouge

The rangoli is auspicious as an invitation to the goddess [Lakshmi] . . . a way to honor and welcome all visitors to the home. The rangoli also is created for important family occasions such as weddings for much the same reason, to attract beauty and luck into the lives of the new couple.

—Jayant Jani, Indian Association of New Orleans leader

Rangoli are pictorial or geometric designs made of colored powders or ground chalk, sometimes paint, often incorporating natural materials such as colored rice, turmeric, ground chili, dried dal (lentils), or flowers. The designs are usually circular and symmetrical, and can represent the endless nature of time, the circle of life, or paths of celestial bodies. Women create rangoli outdoors, near the entrance to a home or temple for holidays such as Divali—the Festival of Lights, and other special occasions. Rangoli's ephemeral quality makes it all the more valued for the work involved, as a symbol of respect for an occasion, and a reminder of the fleeting essence of time.

Life's Seasons and Rhythms: Community Celebrations & Rituals

Often encompassing multiple traditions, celebrations and rituals reflect what is most valued in a culture. Even as they assimilate to life in Louisiana, immigrant communities continue to mark religious observances, commemorations of political or historical events, seasonal or agricultural celebrations, new years' holidays, and personal rites of passage. Whether private family gatherings or large-scale community events, celebrations and rituals are replete with symbolism, bringing people together to reconnect with their cultural roots and teach younger generations about their heritage. Public festivals allow immigrants to share their culture with the broader community. Rituals often effect a transformation, marking the passage from one year to the next, from single to married, from youth to adulthood. All such occasions transform ordinary places and time into something extraordinary, if only for a few hours or days.

New Year, New Beginnings: Vietnamese Têt, New Orleans

Midnight between the last day of the old year and the first day of the new one embodies the meeting of winter and spring, of hunger and plenty, of death and life. Actions that increase good luck or ward off bad luck are emphasized, and correct behavior is followed to begin the new year well. More than a New Year's celebration, Têt is a joyous occasion honoring family values and the cultural community. People gather to enjoy special dishes, watch performances by popular singers and lion dance troupes, and experience the excitement that explodes on the first day of the New Year.

Almost every Vietnamese home has an altar with family photos, offerings of incense, flowers and food, and religious pictures and statues. Before Tét, families carefully decorate the family altar and set out offerings, including the traditional gift of a betel nut on a bit of limestone powder wrapped in areca leaves, called cánh phuong or phoenix wings, symbolizing close family ties. At community celebrations, the Dragon Dance brings good luck for the coming year.

A Beautiful Leave-taking: Muslim Bridal Henna Parties

In Louisiana's larger cities, Muslim mosques serve multicultural immigrant communities as both a spiritual and cultural gathering place. Islam is practiced broadly around the world, encompassing rich traditions that vary according to nationality or culture. Among diverse Middle Eastern Muslim cultures, a henna party figures into pre-wedding rituals. Amidst music, dancing, and a traditional meal, the bride and her female family and friends, often clad in cross-stitch dresses, receive henna decorations for the next day's festivities.

Henna is an ancient tradition, believed to bring love and good fortune, and protect against evil. Henna decorations have been adopted as a mainstream trend but their ritual significance remains strong among immigrant communities. The thawb, or embroidered dress, is a hallmark of Palestinian women's identity. Women wear these floor-length dresses to henna parties, weddings, and other special occasions.

Inas Nazzal of Baton Rouge models a cross-stitched thawb. Photo: Jocelyn Donlon, 2007

Songs to Make the Bride Cry

Growing up in her hometown (or native) Istanbul, Turkey, Neslihan Hoover absorbed "the old traditional music of long ago," which she performed as a young girl at henna parties. Although a festive occasion, the Turkish henna party marks the bride's departure from her childhood home to join her husband's family. Musicians play sad songs intended to make the bride to cry, so she can show her sorrow at leaving her family.

LISTEN: Neslihan Hoover of Bossier City sings "Arda Boylari (The Arda River Narrows),” from her childhood repertoire at henna parties in Turkey. ”Arda Boylari” harks from a time when people chronicled dramatic happenings in song. It tells the story of a young woman who drowned herself in the Arda River on the eve of an arranged marriage to someone other than her true love.

Often encompassing multiple traditions, celebrations and ritual reflect what is most valued in a culture.

—Laura Marcus Green, folklorist

Passage into Womanhood: Mexican Quinceañera, Bernice

Since the 1980s, Bernice, a small rural town in Union Parish, has become home to a growing Latino community, many of whom came from the south central Mexican state of San Luis Potosi for agricultural or poultry processing work. Among the cultural traditions that Mexican immigrants have transplanted from their home country is the quinceañera, an elaborate celebration marking a girl's 15th birthday. The quinceañera begins with a special Catholic Mass, followed by a reception featuring live music, dancing, and food, decorations and party favors often prepared by family and friends.

Above: At their Quinceanera Mass, held at Our Lady of Perpetual Help in Farmerville, Brenda and Leticia Martinez are invited by the priest to reflect on their transition into adulthood, as their godparents present them with gifts of jewelry. During their reception, the twins each receive a "last doll" from their godparents to remind them of childhood years gone by and signal their passage into a time of new responsibilities.

Below: Juanita Lopez enters Our Lady of Perpetual Help Church in Farmerville with her family for her quinceañera Mass. During the quinceañera reception, her father presents her with her last doll.

A Lot to Learn From Each Other . . .

My mother began to teach me how to make the krathongs when I was five or six years old. It is important to me because I love the traditions and culture of where I come from. I do not want to lose our traditions, and I want to be able to show people these days. I think people have a lot to learn from each other.

—Wimol Harwell, Thai community, New Orleans

In New Orleans, Thai community members observe Loy Krathong, the Festival of the Floating Lotus, held during the November full moon. Made from leaves, flowers, candles, and incense, krathongs are set afloat on rivers during the festival. A time of renewal and hope, Loy Krathong celebrates the end of the rainy season, pays homage to ancestors and life's abundance, and acknowledges the importance of water in people's lives.

Acknowledgements

A Better Life for All is based on documentary folklife fieldwork conducted as part of the Louisiana Folklife Program's New Populations Project. From 2005-2012, researchers reached out to our state's immigrant and refugee communities to engage them in the identification and documentation of their traditional arts.

The Louisiana Division of the Arts Folklife Program and the Louisiana State Museum gratefully acknowledge the support of the National Endowment for the Arts, which made the New Populations initiative possible. Thanks also go to the researchers whose work has illuminated the state's vibrant immigrant heritage, including:

Dominic Bordelon, Martha Brown, Kathleen Carlin, Barbara Chumley, Jocelyn Hazelwood Donlon, Jon Donlon, Laura Marcus Green, Emma Tomingas-Hatch, Mindy McClain, Andrew McClean, Denese Neu, Brother Thieu Nguyen, Father Vien The Nguyen, Maida Owens, Susan Roach, Devon Robbie, Amy Serrano, Mark Sindler, Cam-Thanh Tran, Allison Truitt, Guiyuan Wang, Carolyn Ware, Laura Westbrook, Daria Woodside

Most of all, appreciation is due the traditional artists and community members who so generously shared their knowledge and time, and the beauty of their cultural traditions.

The exhibit was curated in 2014 by folklorist Laura Marcus Green; Maida Owens, director of the Louisiana Division of the Arts Folklife Program; and historian Karen Leathem with the Louisiana State Museum. It was designed by Nalini Raghavan.

Laura Marcus Green, a folklorist based in Santa Fe, New Mexico, wrote this expanded version of the exhibit in 2013 for A Better Life for All: Traditional Arts of Louisiana's Immigrant Communities for the New Populations Project.

Explore Louisiana's New Populations

Learn more: find online essays resulting from this project here.

Explore Louisiana's New Populations

Introduction

Chinese

Cubans

Filipinos

Garifuna

Germans

Guatemalans

Hondurans

Indians

Japanese

Laotians

Latinos/Hispanics

Mexicans

Middle Eastern Muslims

Nicaraguans

Thai

Vietnamese

Shreveport - Bossier City

Other Articles on Louisiana's New Populations:

These articles were written through initiatives other than the New Populations Project.

Exhibitor Kit

An exhibitor kit provides activities to augment visitors experience when visiting the traveling exhibit or when viewing the exhibit online.